mindmap

root((Regression

Analysis)

Continuous <br/>Outcome Y

{{Unbounded <br/>Outcome Y}}

)Chapter 3: <br/>Ordinary <br/>Least Squares <br/>Regression(

(Normal <br/>Outcome Y)

{{Nonnegative <br/>Outcome Y}}

)Chapter 4: <br/>Gamma Regression(

(Gamma <br/>Outcome Y)

Discrete <br/>Outcome Y

4 Gamma Regression

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Explain what Gamma regression is and when it is appropriate to use

- Recognize the types of problems suited for Gamma regression, especially those with positive, skewed outcomes

- Describe the Gamma distribution and how its shape is influenced by its parameters

- Understand the role of the link function, especially the log link, in Gamma regression

- Set up a Gamma regression model using a log link and interpret its coefficients in the context of the original variables

- Evaluate model fit using deviance residuals, spread patterns, and AIC

4.1 Introduction

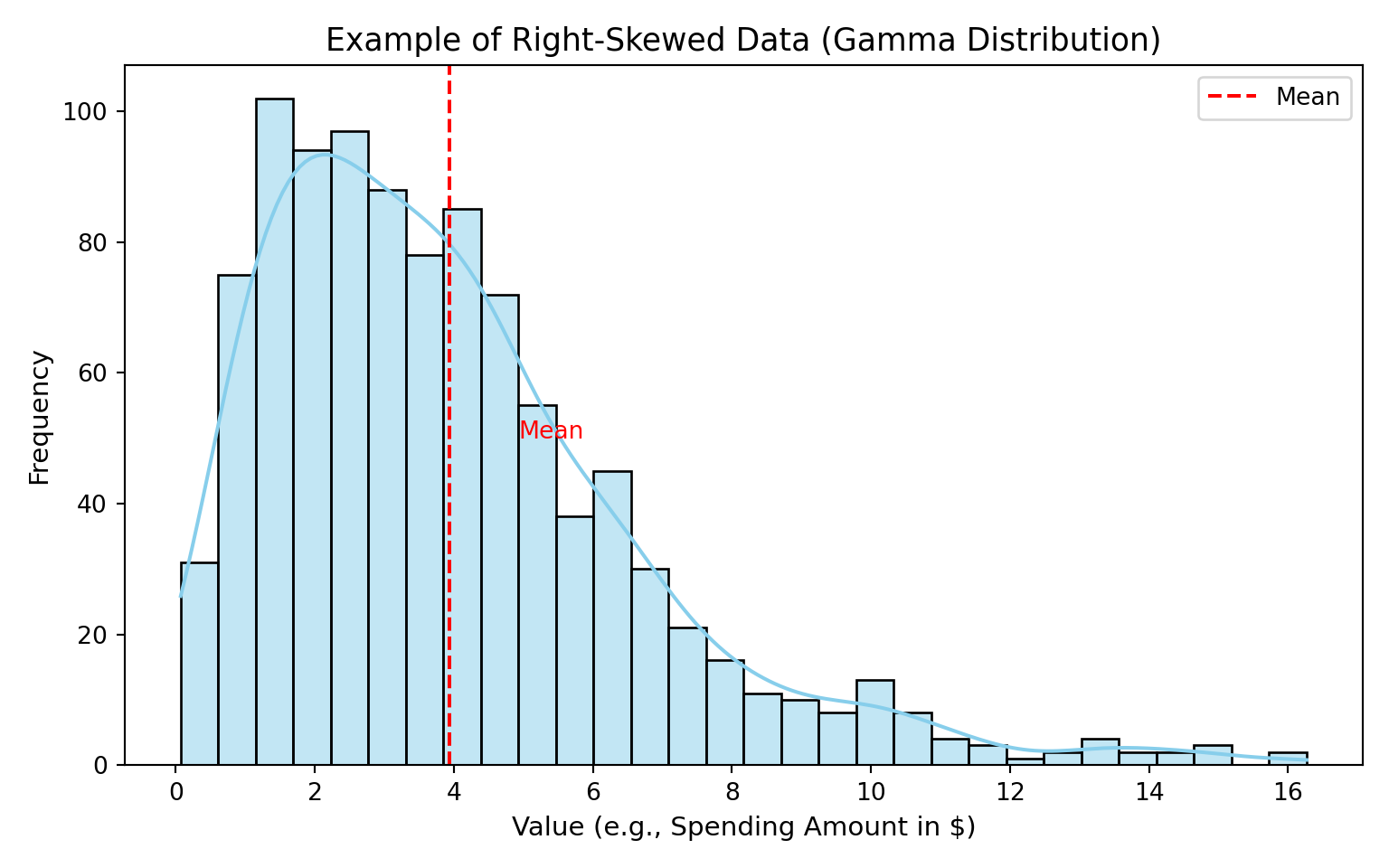

Some types of data are always positive and tend to have a few really large values. For example, imagine we are looking at how much people spend at a grocery store. Most people might spend a small to medium amount, but a few people might spend a lot more. This kind of data is not evenly spread out, and it does not look like a nice bell curve. Instead, it is skewed to the right, with a long tail of higher numbers.

In these situations, the usual type of regression (called ordinary least squares, or OLS) does not work very well. OLS assumes that the data is evenly spread out around the average and that big values and small values are equally likely. But when we have only positive numbers and some very big ones, we need a different approach.

This is where Gamma regression can help.

4.2 What is Gamma Regression

Gamma regression is a tool we use when the outcome we are trying to predict is always positive and can vary a lot. For example, we might want to predict:

- how long it takes for someone to complete a task

- how much money someone spends at a store

- the cost of a medical procedure

These types of outcomes are positive, continuous, and often right-skewed: most values are small or moderate, but a few can be extremely large. This uneven spread makes the data a poor fit for regular linear regression, which assumes that the outcomes are roughly symmetric and that the variability stays constant across all levels of the predictors.

Gamma regression is designed for situations like this. Instead of trying to fit a straight line with constant variance, it uses a model that:

- respects the fact that the outcome must be positive, and

- allows the variance to grow with the mean, which matches how many real-world cost or duration variables behave.

4.3 Understanding the Gamma Distribution

Gamma regression is built on something called the Gamma distribution. This distribution is used to describe values that are:

- always above zero

- and can have a long tail of larger values

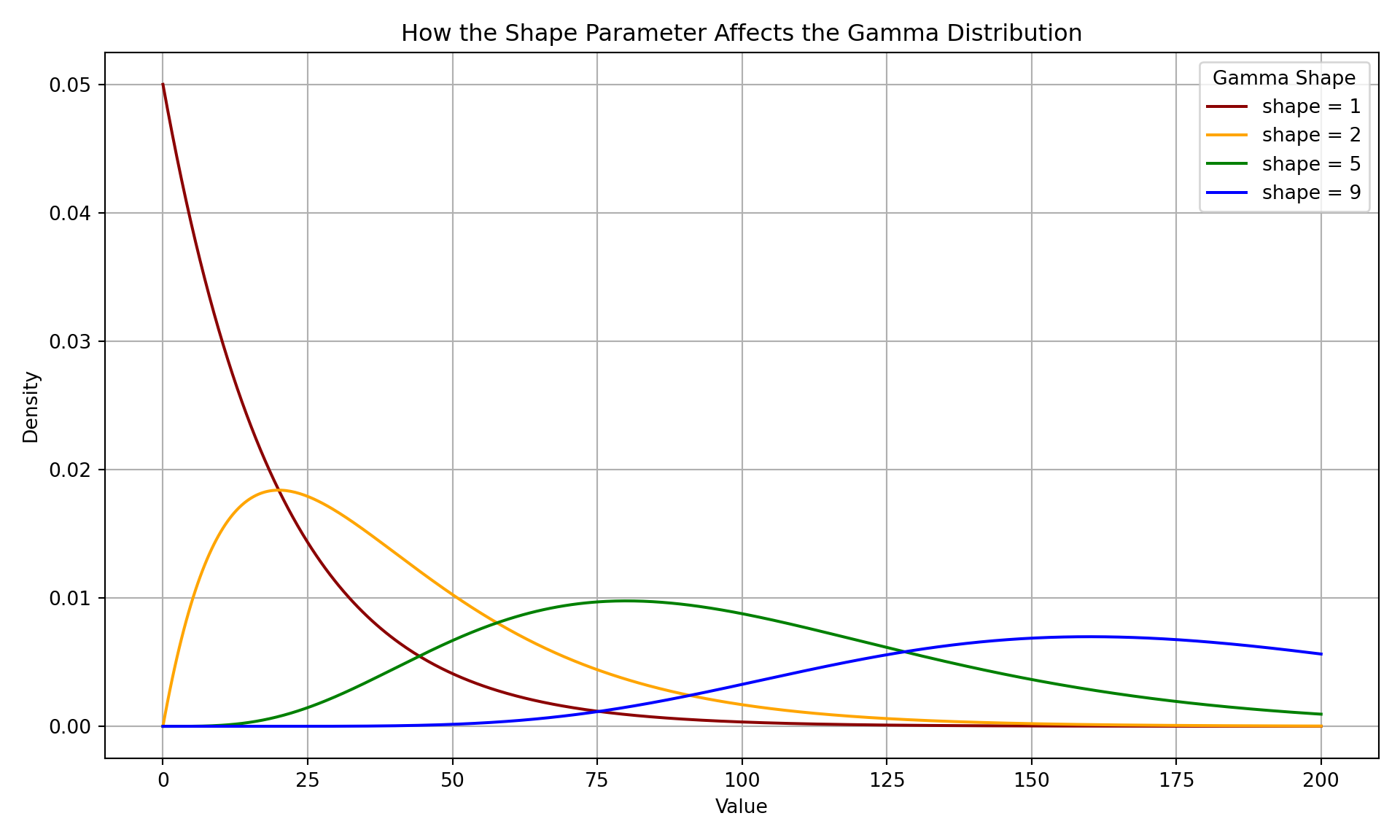

What makes the Gamma distribution flexible is a number called the shape parameter. This controls how the data is spread out.

- When the shape is small (like 1), the distribution is very skewed. Most values are small, but a few are much larger.

- When the shape is larger (like 5 or 9), the curve becomes more balanced, though it still never includes negative numbers.

Let’s look at what this means visually:

The plot above shows how the shape parameter changes the look of the Gamma distribution. It helps explain why Gamma regression is such a good match for skewed data. In the frequentist paradigm, we aim to find the Gamma distribution with the shape parameter that best fits the observed data.

4.4 How Gamma Regression Works

Now that we know what Gamma regression is and the kinds of problems it solves, let’s look at how it actually works.

The key idea is that Gamma regression doesn’t model the outcome values directly. Instead, it focuses on the average outcome and relates it to predictors in a way that respects the positive, skewed nature of the data.

To understand this, we need to take a step back and talk about a broader family of models called Generalized Linear Models, or GLMs. These are a flexible class of models that let us deal with many types of data, not just bell-shaped curves. GLMs allow us to model outcomes that are counts, proportions, or, as in our case, continuous and strictly positive. In this next section, we’ll break down what this means.

4.4.1 Generalized Linear Models

Definition of Generalized Linear Models

Generalized Linear Models (GLMs) are a powerful extension of linear regression. They allow us to model a wide variety of response variables beyond just those that follow a normal distribution. This makes GLMs especially useful in real-world situations where data often breaks the assumptions of ordinary least squares (OLS) regression.

Before we introduce the full GLM framework, let’s start with a simple example that shows why a standard linear model isn’t always appropriate. This will help motivate why we need a more general approach in the first place.

Problem with Linear Regression for Non-Normal Data

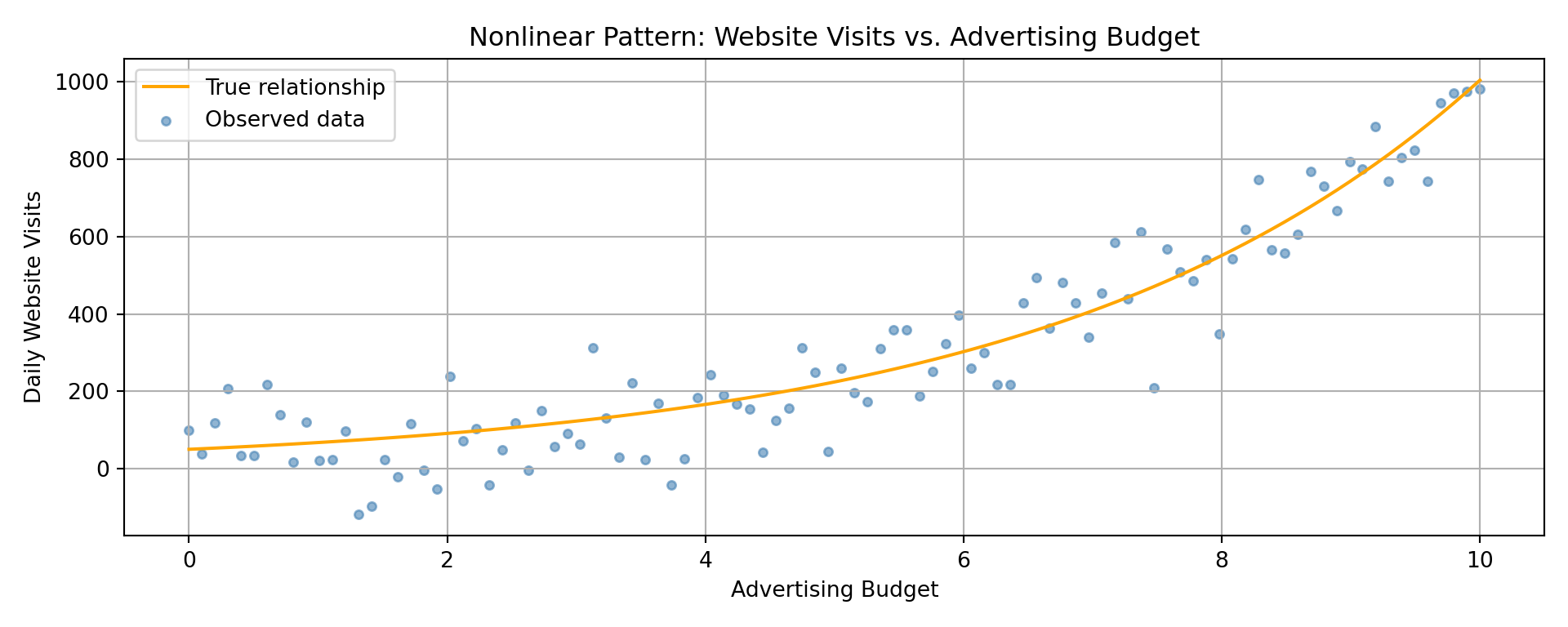

Suppose we want to model the number of daily website visits for a company, based on the company’s advertising budget. This outcome is:

- always positive

- right-skewed

- and often grows rapidly with budget

Let’s simulate this data:

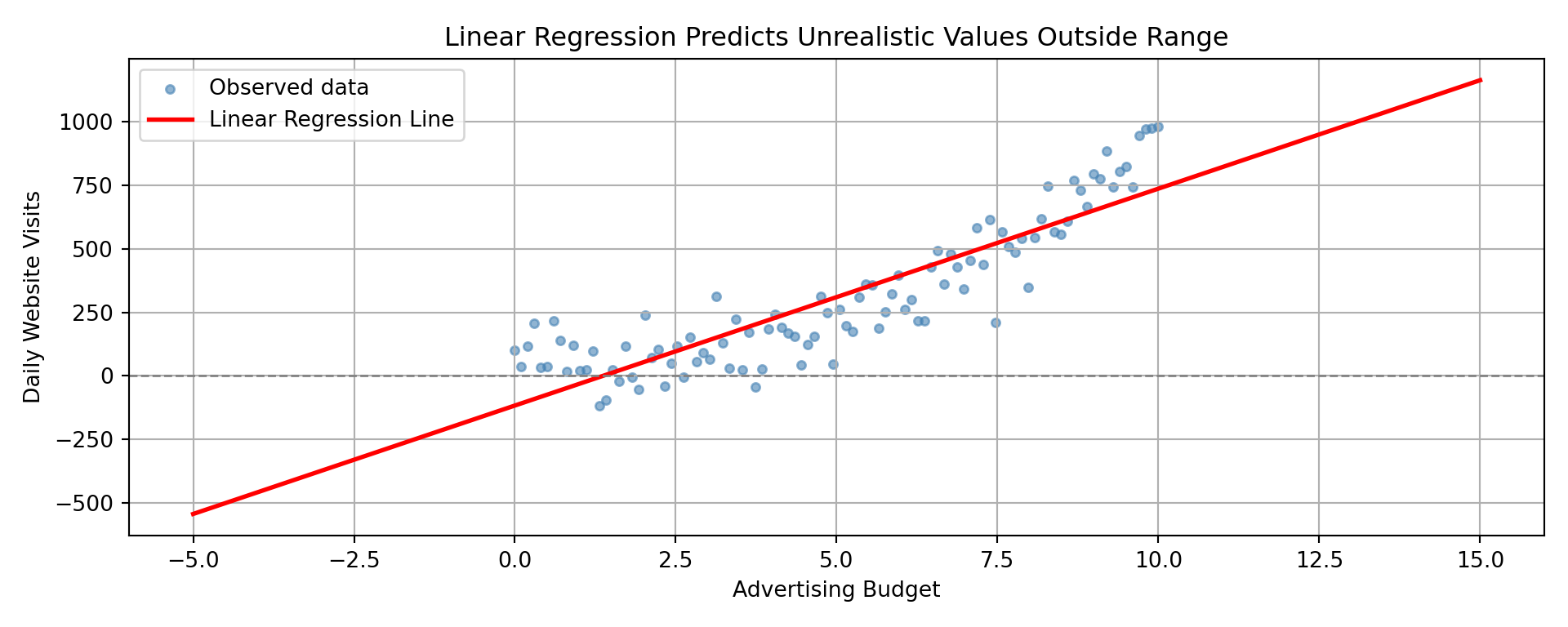

Linear regression tries to fit a straight line through this data, but the result is clearly problematic.

We run into several issues here:

- Predictions can be negative, which makes no sense for visit counts

- Predictions do not capture the multiplicative or curved nature of the relationship

- Variability grows with the mean, violating the constant variance assumption

These problems stem from assumptions built into OLS:

- The outcome is normally distributed

- The outcome has constant variance

- The relationship between predictors and outcome is linear

When those assumptions are broken, OLS can give misleading or invalid results.

What GLMs Do Differently

Despite these problems, linear regression has a big strength: it’s interpretable. The formula tells us exactly how the outcome changes with the predictor. But wouldn’t it be great if we could retain this interpretability while also accounting for the data’s quirks? That’s what Generalized Linear Models do.

The original linear regression formula looks like this:

\[ \mu = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x \]

As demonstrated above, this assumes \(\mu\) (the expected outcome) can take any real value, including negatives, and grows in a straight-line fashion, which just doesn’t make much sense given the data.

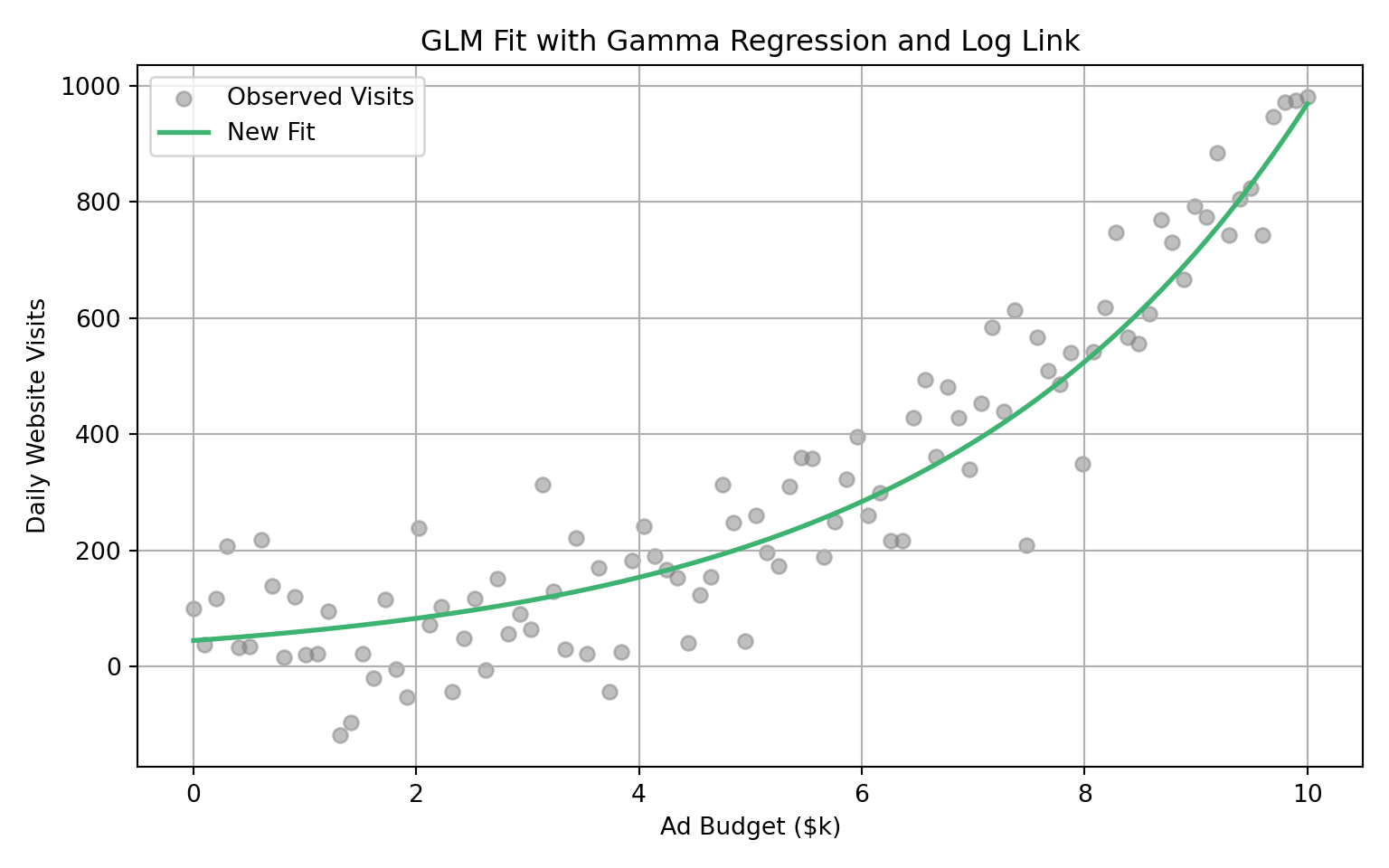

Now, imagine we make one small change, apply a log transformation to the mean:

\[ \log(\mu) = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x \]

This small adjustment makes a huge difference. Here’s how the fitted curve now looks with this small change:

This new setup has several advantages:

- All predicted values of \(\mu\) are strictly positive

- The relationship between predictors and response is multiplicative, not additive

- The variance increases with the mean, which reflects how real-world data often behaves

- We still retain a straight-line interpretation, but now it’s on the log scale

What you have just witnessed is an example of Generalized Linear Model. It is a flexible extension of linear regression that allows you to model outcomes in a way that reflects how they are actually distributed, while also preserving the ability to interpret coefficients like in linear regression

The Three Components of GLM

Now that we have seen an example of a GLM, let’s properly introduce the components that make up a GLM. Every Generalized Linear Model (GLM) is built on the same three key components. This structure gives GLMs the flexibility to model many types of data while still being easy to interpret.

1. Random Component (Distribution of the Response)

This specifies how the response variable is distributed. In linear regression, the response is normally distributed. But GLMs allow for many other distributions, depending on what kind of data you are modeling.

| Type of Data | Example Distribution |

|---|---|

| Continuous, symmetric | Normal |

| Count | Poisson |

| Proportion or binary | Binomial |

| Positive, skewed | Gamma |

This is where the flexibility of GLMs comes from. You choose a distribution that matches your outcome.

2. Systematic Component (Linear Predictor)

This is the familiar part from linear regression. It is a linear combination of the predictors:

\[ \begin{align*} \eta &= \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_{1} + \beta_2 x_{2} + \cdots + \beta_p x_{p} \end{align*} \]

This linear predictor, often denoted by \(\eta\), is the foundation of the model. The link function (coming next) will connect this to the mean of the response variable.

3. Link Function (Connecting Predictors to the Mean)

The link function transforms the expected value of the response variable so that it can be modeled as a linear combination of predictors.

\[ \begin{align*} g(\mu) = \eta &= \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_{1} + \beta_2 x_{2} + \cdots + \beta_p x_{p} \end{align*} \]

Different distributions tend to pair with different link functions:

| Distribution | Typical Link Function | Equation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | Identity | \(\mu = \eta\) |

| Binomial | Logit | \(\log\left( \frac{\mu}{1 - \mu} \right) = \eta\) |

| Poisson | Log | \(\log(\mu) = \eta\) |

| Gamma | Log | \(\log(\mu) = \eta\) |

The link function helps ensure that predictions stay within a valid range (e.g., probabilities stay between 0 and 1, counts stay positive, etc.).

Gamma Regression as a GLM

Now that we’ve introduced the components of a GLM, we can see that Gamma regression is not a completely new type of model. Instead, it is one specific case within the broader GLM framework. What makes Gamma regression special is that it is designed for situations where the outcome:

- is strictly positive

- tends to be right-skewed

- and often shows larger variance when the mean is higher

To make this concrete, let’s specify the three GLM components as they apply to Gamma regression:

1. Random Component (Gamma)

The response variable \(Y\) is assumed to follow a Gamma distribution, which is continuous, strictly positive, and right-skewed. The variance of \(Y\) increases with its mean, often expressed as: \[ \operatorname{Var}(Y_i) = \phi \mu_i^2 \]

This makes Gamma regression a good match for data where larger expected values come with more uncertainty.

2. Systematic Component (Gamma)

Just like in linear regression, the predictors are combined linearly:

\[ \eta_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_{i1} + \beta_2 x_{i2} + \cdots + \beta_p x_{ip} \]

This linear predictor \(\eta_i\) serves as the backbone of the model.

3. Link Function (Gamma)

To connect the predictors to the expected outcome \(\mu_i = \mathbb{E}(Y_i)\), Gamma regression uses the log link:

\[ \log(\mu_i) = \eta_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_{i1} + \cdots + \beta_p x_{ip} \]

This ensures that:

- All predicted values of \(\mu_i\) are strictly positive

- The relationship between predictors and the mean is multiplicative, not additive

- We can interpret coefficients on the log scale, preserving interpretability

In other words, Gamma regression is just a GLM with a Gamma distribution and a log link. It does not model the outcome values directly. Instead, it focuses on the average outcome and relates it to predictors in a way that respects the positive, skewed nature of the data.

4.5 When to Use and Not Use Gamma Regression

With the core ideas of Gamma regression in place, we can now summarize the practical guidelines: the situations where Gamma regression is most effective, and the situations where it is not recommended.

When to Use and Not Use Gamma Regression

Gamma regression is powerful, but it isn’t a one-size-fits-all tool. It shines in some situations and breaks down in others. The checklist below can help you decide.

Use Gamma regression when:

- The outcome is continuous and strictly positive (e.g., insurance claim amounts, pollutant concentrations, operational spending).

- Observations are statistically independent.

- The distribution is right-skewed, where variance grows faster than the mean.

- You want to model the logarithm of the mean as a link function, which guarantees positive predictions.

Avoid Gamma regression when:

- The outcome includes zeros or negative values.

- The outcome is a count variable. In that case, consider alternatives like Classical Poisson, Negative Binomial, Zero-Inflated Poisson or Generalized Poisson.

- The variance increases at a constant rate with the mean, rather than at a faster rate (a sign another GLM family may be more appropriate).

4.6 Case Study: Modeling Web Server Performance

To demonstrate Gamma regression in action, we will walk through a case study using a toy dataset. This case study will help us understand what affects the response time of a web server. Specifically, how long it takes (in milliseconds) for the server to respond to a user’s request.

We will approach this case study using the data science workflow introduced in the first chapter. This ensures a structured approach to framing the problem, selecting a model, and building an interpretation based on the model’s results.

4.6.1 The Dataset

The toy dataset used to demonstrate captures various features of web requests across different servers and regions. Each row represents a single request and contains information about the server load, the number of users at the time, how complex the request was, and other related factors. Below is a summary of the variables:

| Variable Name | Description |

|---|---|

| response_time_ms | The time it takes for the server to respond to a request (in milliseconds). |

| concurrent_users | Number of users on the server at the time of the request. |

| database_queries | Number of database queries triggered by the request. |

| cache_hit_rate | Percentage of data requests served from the cache (0 to 100). |

| server_load | Server CPU load at the time of the request (0 to 100). |

| time_of_day | Hour of the day when the request was made (0 = midnight, 23 = 11 PM). |

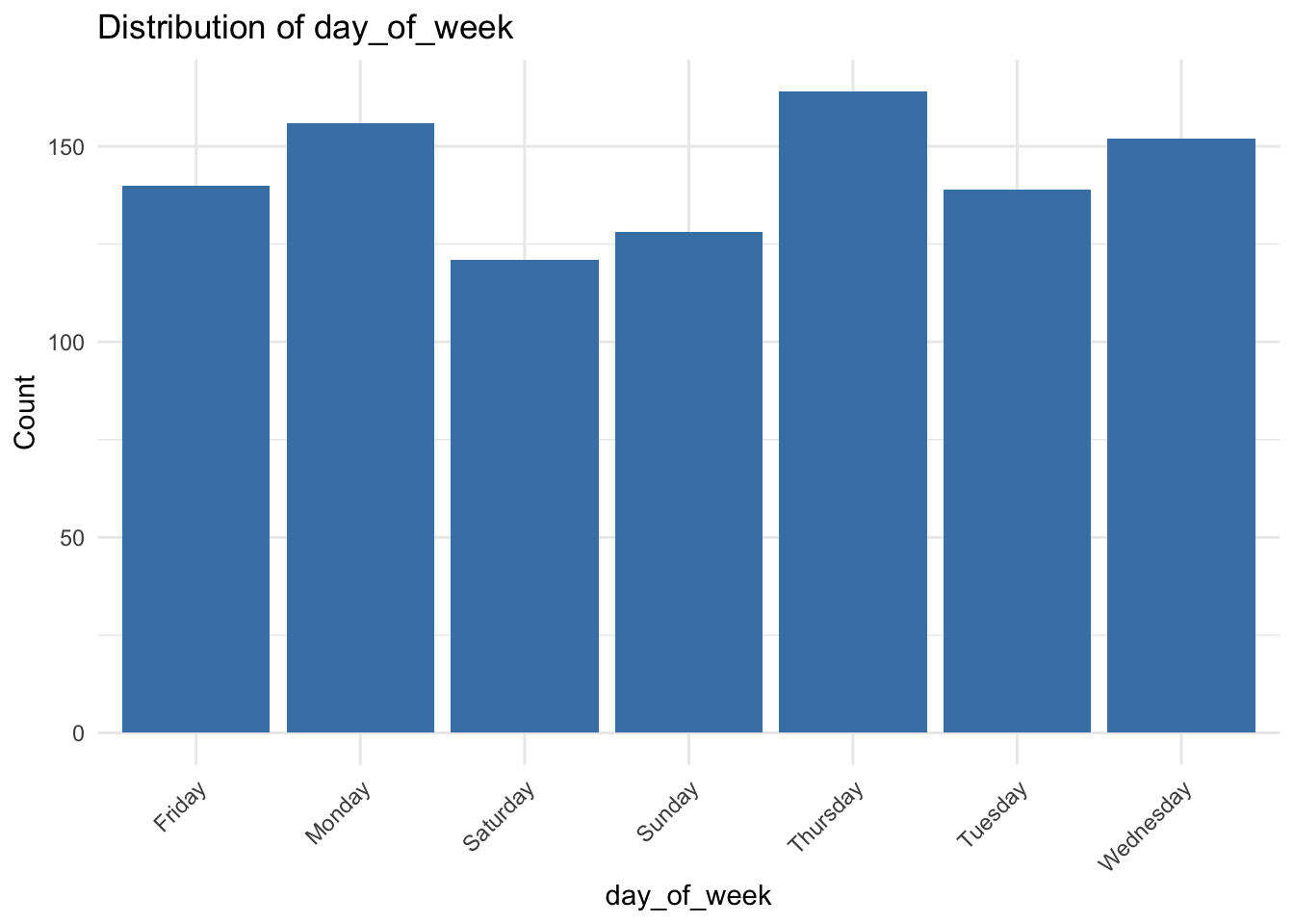

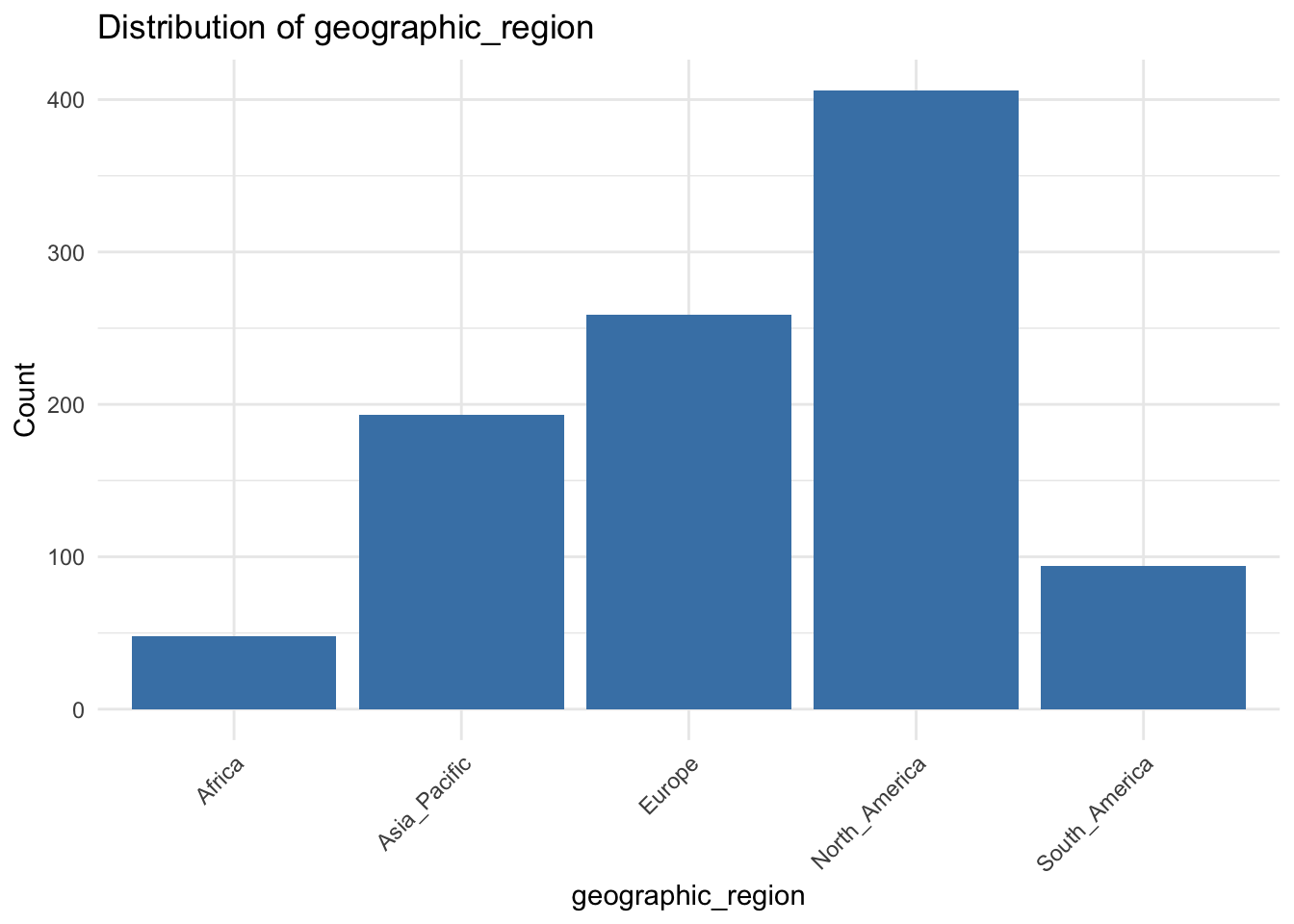

| day_of_week | Day of the week (e.g., Monday, Tuesday). |

| geographic_region | Geographic region where the request originated. |

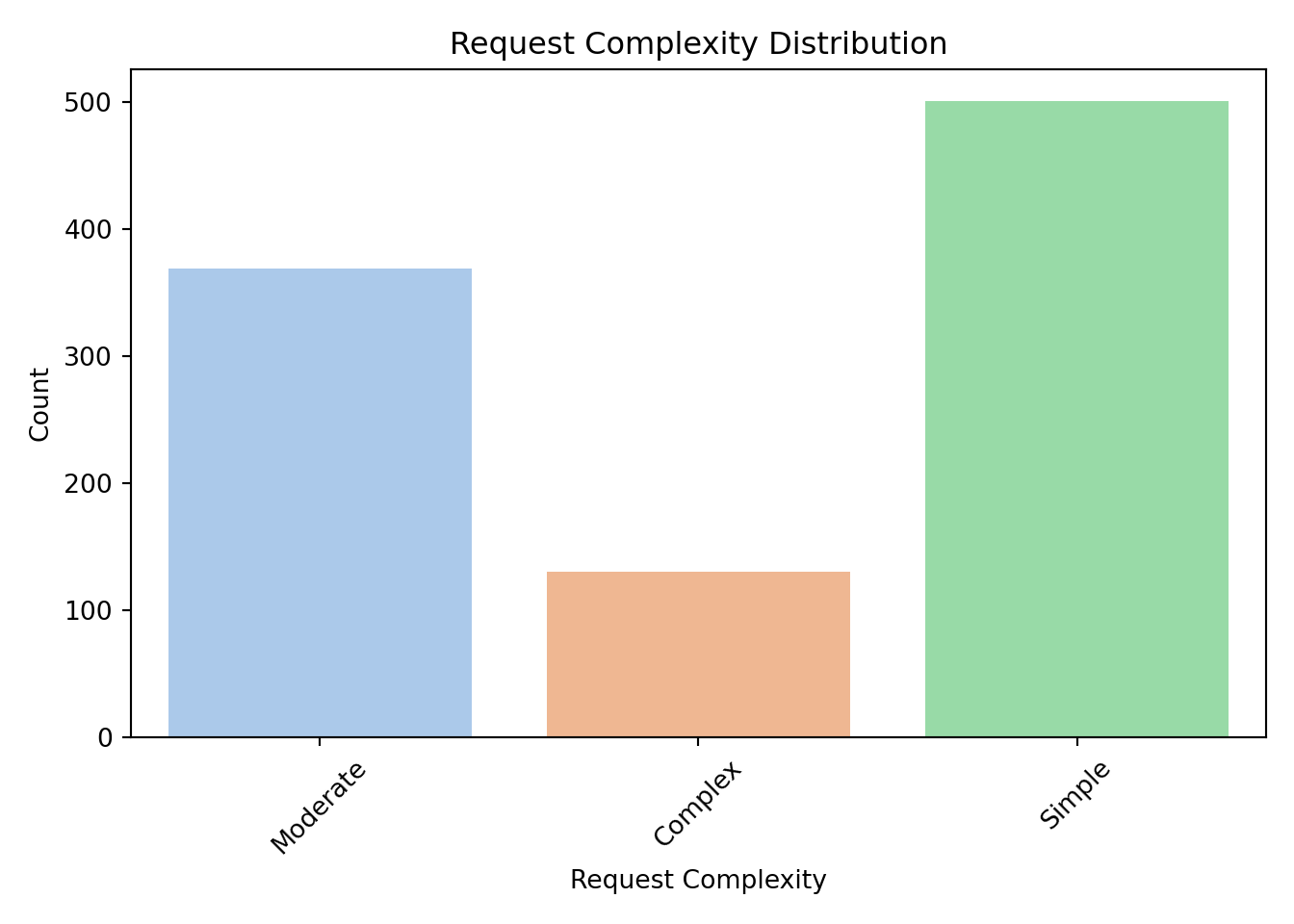

| request_complexity | Categorical value describing request complexity: “Simple”, “Moderate”, or “Complex”. |

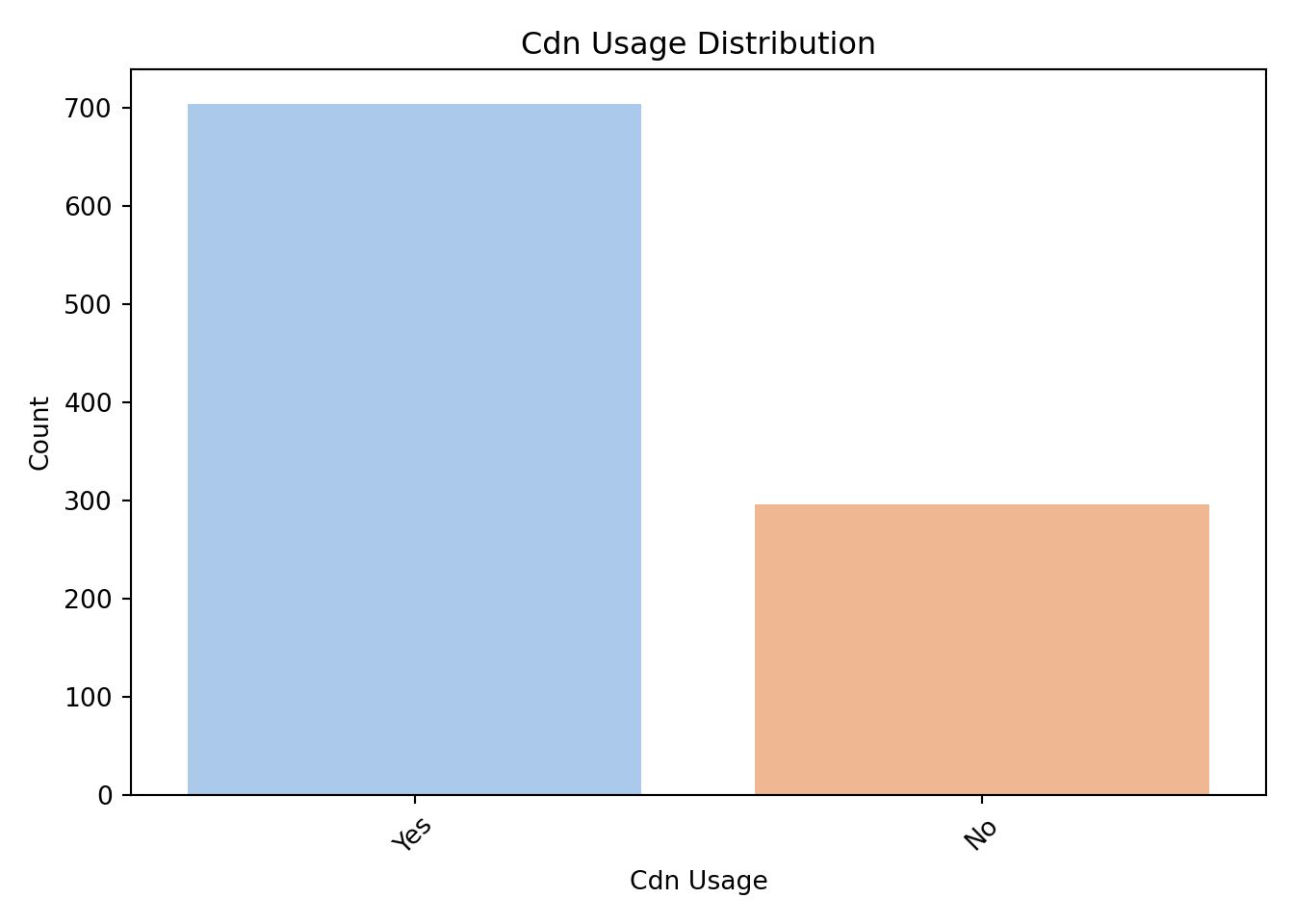

| cdn_usage | Whether a content delivery network was used (“Yes” or “No”). |

| memory_usage | Memory used on the server at the time of request (in percent). |

Here’s a snapshot of the dataset:

| response_time_ms | concurrent_users | database_queries | cache_hit_rate | server_load | time_of_day | day_of_week | geographic_region | request_complexity | cdn_usage | memory_usage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 54.2 | 40 | 10 | 94.8 | 61.4 | 8 | Saturday | North_America | Moderate | Yes | 63.6 |

| 28.6 | 148 | 1 | 56.1 | 43.2 | 18 | Thursday | North_America | Complex | Yes | 25.5 |

| 50.2 | 195 | 14 | 94.6 | 67.0 | 1 | Thursday | North_America | Complex | No | 26.6 |

| 24.8 | 82 | 10 | 77.9 | 83.9 | 14 | Monday | Africa | Simple | Yes | 67.5 |

| 127.1 | 85 | 10 | 58.7 | 47.1 | 7 | Thursday | South_America | Moderate | Yes | 54.4 |

This dataset allows us to analyze performance differences in web servers under different conditions and determine what contributes to longer or shorter response times.

4.6.2 The Problem We’re Trying to Solve

In this case study, our goal is to analyze what drives differences in web server response times. Because response time is continuous, strictly positive, and often right-skewed, Gamma regression is a natural choice for modeling it.

The key question we aim to answer is:

Which server or request characteristics have the biggest influence on response time?

Answering this question requires more than just prediction. It requires understanding the relationships between server conditions, request features, and performance. In the next section, we’ll clarify our study design and show how Gamma regression supports this goal.

4.7 Study Design

In this case study, our goal is to understand what drives differences in web server response times. Because response time is continuous, strictly positive, and often right-skewed, Gamma regression is a natural modeling choice.

The broader objective is to uncover which server or request characteristics meaningfully influence response time. This requires more than simply forecasting future values. It requires understanding how different factors relate to average performance.

To make that purpose precise, we turn to the study design.

4.7.1 Inferential vs. Predictive Analysis

Following the data science workflow, our first step is to define the purpose of the analysis. As mentioned, our guiding question is:

Which server or request characteristics have the biggest influence on response time?

This question can be approached in two different ways, inferential or predictive, depending on what we want the analysis to achieve.

Inferential analysis helps us understand and quantify how different variables affect the average outcome. For example: Does using a content delivery network (CDN) significantly reduce response time? How much slower are complex requests compared to simple ones?

Predictive analysis, by contrast, is about making accurate forecasts. For instance: Can we predict the response time of a future request based on its characteristics?

Gamma regression can be used for either purpose, but our focus in this chapter is inferential, since our goal is to explain and quantify how different factors influence response time.

To that end, we will use Gamma regression to estimate how each feature affects the average response time while properly accounting for skewness in the outcome. This allows us to answer questions such as:

- How do concurrent users affect response time?

- Does request complexity lead to slower responses?

- What is the typical effect of CDN usage?

- How are server load and memory usage related to delays?

Our goal is not to build a black-box predictor, but to uncover which factors matter most and how they shape server performance, insights that can guide system tuning, policy decisions, and resource planning.

4.8 Data Collection and Wrangling

With our statistical question clearly defined, the next step is to make sure the data is suitable for analysis. Although we already have the dataset, it is useful to reflect on how this type of server performance data might have been collected. Understanding the data collection process helps us recognize potential limitations and prepare the data appropriately.

4.8.1 Data Collection

For a study like this, where we analyze server response times across different conditions, data could have been collected through several common methods:

Server Logs: Most web servers automatically record detailed logs of every request. These logs typically include information like timestamps, request types, response time, server load, and geographic origin. This is a likely source for our dataset and provides reliable, machine-recorded data.

Monitoring Tools: Infrastructure monitoring platforms such as New Relic, Datadog, or AWS CloudWatch can capture performance metrics in real time. These tools often collect a richer set of metrics, including CPU usage, memory usage, and cache hit rates.

Simulated Load Testing: In controlled environments, engineers may run scripted performance tests to evaluate how different types of requests behave under varying traffic loads. While simulated data offers consistency, it may not reflect real-world user behavior.

Each data collection method has its own strengths and trade-offs:

- Server logs are objective but may lack high-level context (such as request complexity or user intent).

- Monitoring tools are detailed but might involve sampling or missing values due to downtime.

- Simulated tests offer control but may lack realism.

Regardless of how the data was collected, it’s important to check for common issues such as:

- Missing values in fields like server load or memory usage

- Incorrect or inconsistent formatting (e.g., “Yes” vs “yes” vs “TRUE”)

- Outliers in response time that may skew the results

- Categorical variables that need to be converted into a numerical format for modeling

All of these issues will be addressed in the next stage, data wrangling.

4.8.2 Data Wrangling

Once the data has been collected, the next step is to prepare it for modeling. Even reliable sources like server logs or monitoring tools produce raw data that needs cleaning before it can be used effectively.

For Gamma regression, data wrangling typically involves:

- Validating the response variable to ensure all values are strictly positive and meaningful.

- Transforming categorical variables (e.g., request complexity, geographic region) into numerical formats that the model can handle.

- Checking for missing values or extreme outliers that could bias results.

- Scaling or normalizing predictors if large differences in measurement units make interpretation difficult.

Let’s walk through how to apply these steps to our dataset.

1. Validating the Response Variable

Gamma regression assumes the outcome is strictly positive and continuous, making it a good fit for response_time_ms, which records how long the server takes to respond to a request.

Before fitting the model, we need to confirm that all values in response_time_ms are greater than zero:

summary(gamma_server$response_time_ms) Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

0.50 19.18 49.05 93.32 111.45 1561.00 # Summary statistics for the response variable

print(data["response_time_ms"].describe())count 1000.000000

mean 93.320300

std 141.940277

min 0.500000

25% 19.175000

50% 49.050000

75% 111.450000

max 1561.000000

Name: response_time_ms, dtype: float64# Check for any non-positive values

print((data["response_time_ms"] <= 0).sum())0The summary confirms that all values are strictly positive, so response_time_ms is suitable for Gamma regression. If zeros or negative values had been present, we may need to remove them, add a small offset, or just opt for another regression technique.

2. Encoding Categorical Variables

Like most regression and machine learning models, Gamma regression requires all inputs to be numeric. This means categorical variables must be converted into numerical form. In our dataset, this includes:

day_of_weekgeographic_regionrequest_complexitycdn_usage

The standard approach is one-hot encoding, where each category is represented by a new binary column (0 or 1). For example, the variable request_complexity with three categories (Simple, Moderate, Complex) would become:

request_complexity_Simplerequest_complexity_Moderaterequest_complexity_Complex

To avoid multicollinearity (perfect correlation among dummies), we drop one category from each group. The dropped category becomes the reference level that all other categories are compared against.

gamma_server_encoded <- fastDummies::dummy_cols(

gamma_server,

select_columns = c("day_of_week", "geographic_region", "request_complexity", "cdn_usage"),

remove_first_dummy = TRUE,

remove_selected_columns = TRUE

)

# Print resulting column names

colnames(gamma_server_encoded) [1] "response_time_ms" "concurrent_users"

[3] "database_queries" "cache_hit_rate"

[5] "server_load" "time_of_day"

[7] "memory_usage" "day_of_week_Monday"

[9] "day_of_week_Saturday" "day_of_week_Sunday"

[11] "day_of_week_Thursday" "day_of_week_Tuesday"

[13] "day_of_week_Wednesday" "geographic_region_Asia_Pacific"

[15] "geographic_region_Europe" "geographic_region_North_America"

[17] "geographic_region_South_America" "request_complexity_Moderate"

[19] "request_complexity_Simple" "cdn_usage_Yes" import pandas as pd

# Perform one-hot encoding, drop first level from each category

categorical_vars = ["day_of_week", "geographic_region", "request_complexity", "cdn_usage"]

# Create dummy variables, drop first category from each

data_encoded = pd.get_dummies(data, columns=categorical_vars, drop_first=True)

# Print resulting column names

print(data_encoded.columns.tolist()) ['response_time_ms', 'concurrent_users', 'database_queries', 'cache_hit_rate', 'server_load', 'time_of_day', 'memory_usage', 'day_of_week_Monday', 'day_of_week_Saturday', 'day_of_week_Sunday', 'day_of_week_Thursday', 'day_of_week_Tuesday', 'day_of_week_Wednesday', 'geographic_region_Asia_Pacific', 'geographic_region_Europe', 'geographic_region_North_America', 'geographic_region_South_America', 'request_complexity_Moderate', 'request_complexity_Simple', 'cdn_usage_Yes']This step ensures that all features going into the Gamma regression model are numeric and suitable for estimation. It also allows us to interpret the effect of each category relative to the baseline, which is the dropped category from each group.

For example, the variable request_complexity originally had three categories: Simple, Moderate, and Complex. After encoding, the dataset contains two dummy variables:

request_complexity_Simplerequest_complexity_Moderate

Here, Complex has been dropped and serves as the reference category. This means:

- The coefficient for

request_complexity_Simpletells us how much faster or slower requests marked asSimpleare compared toComplex. - The coefficient for

request_complexity_Moderatetells us the difference betweenModerateandComplex.

This same logic applies to all other categorical variables: one level is chosen as the baseline, and all coefficients are interpreted relative to it.

3. Checking for Missing Values

Before fitting a regression model, it’s important to confirm that the dataset has no gaps. Missing values can cause estimation errors or lead to dropped observations if not handled properly.

response_time_ms concurrent_users

0 0

database_queries cache_hit_rate

0 0

server_load time_of_day

0 0

memory_usage day_of_week_Monday

0 0

day_of_week_Saturday day_of_week_Sunday

0 0

day_of_week_Thursday day_of_week_Tuesday

0 0

day_of_week_Wednesday geographic_region_Asia_Pacific

0 0

geographic_region_Europe geographic_region_North_America

0 0

geographic_region_South_America request_complexity_Moderate

0 0

request_complexity_Simple cdn_usage_Yes

0 0 # Count missing values in each column

data_encoded.isna().sum()response_time_ms 0

concurrent_users 0

database_queries 0

cache_hit_rate 0

server_load 0

time_of_day 0

memory_usage 0

day_of_week_Monday 0

day_of_week_Saturday 0

day_of_week_Sunday 0

day_of_week_Thursday 0

day_of_week_Tuesday 0

day_of_week_Wednesday 0

geographic_region_Asia_Pacific 0

geographic_region_Europe 0

geographic_region_North_America 0

geographic_region_South_America 0

request_complexity_Moderate 0

request_complexity_Simple 0

cdn_usage_Yes 0

dtype: int64If missing values were present, we would need to either:

- Remove rows with missing values (simple but may reduce sample size), or

- Impute values using the mean, median, or another suitable method.

In our toy dataset, all variables are complete, so no further action is needed here.

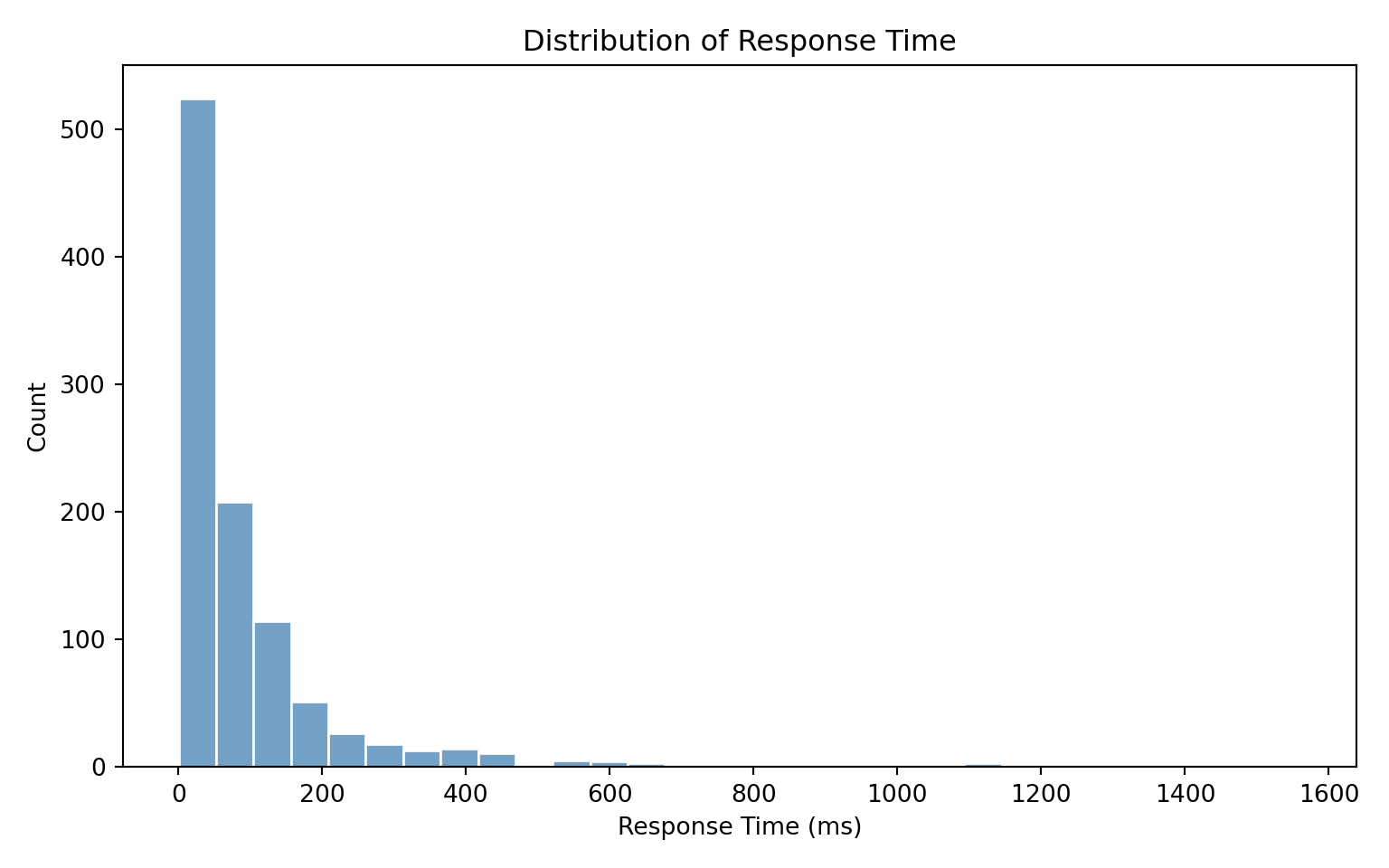

4. Examining Potential Outliers

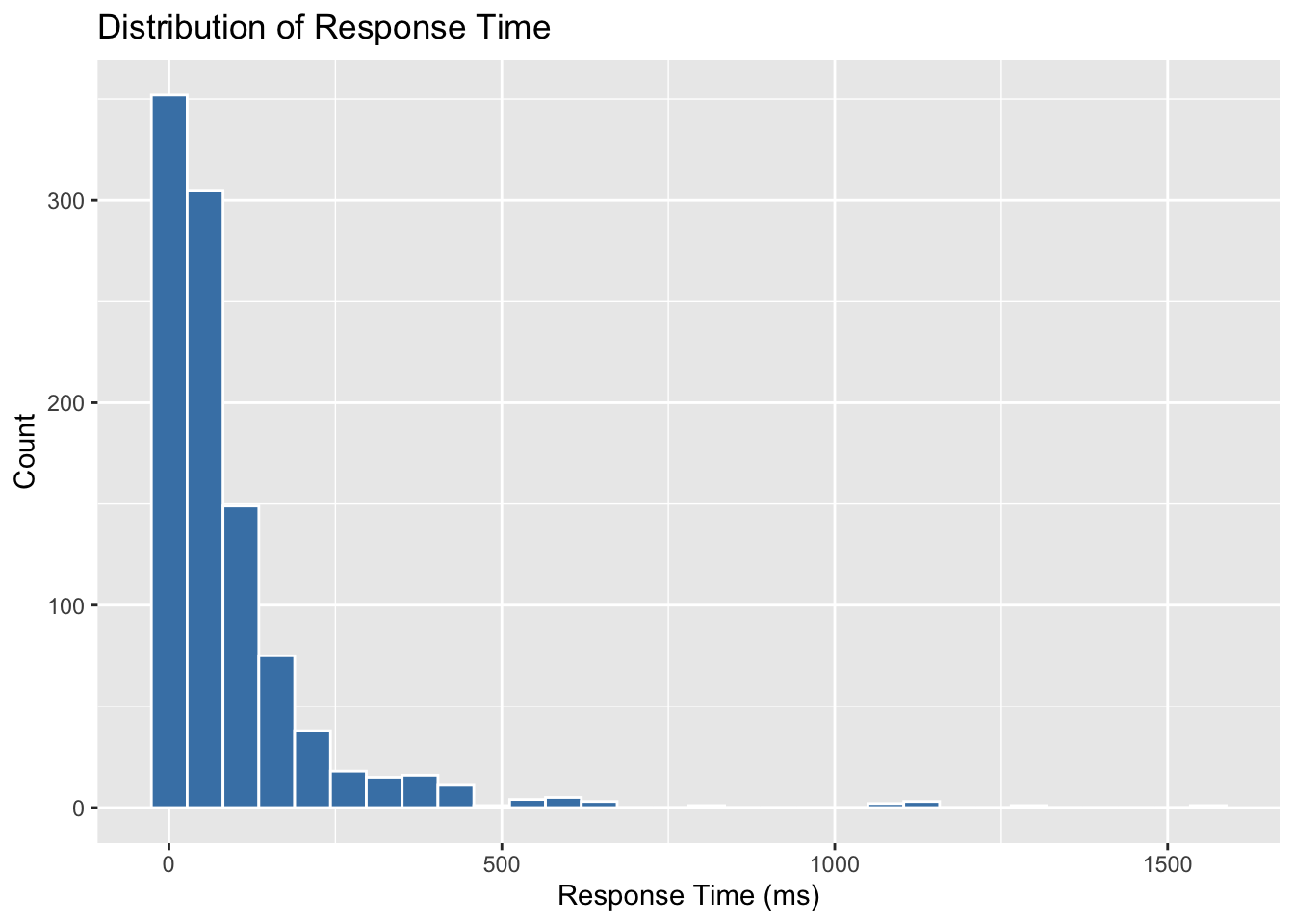

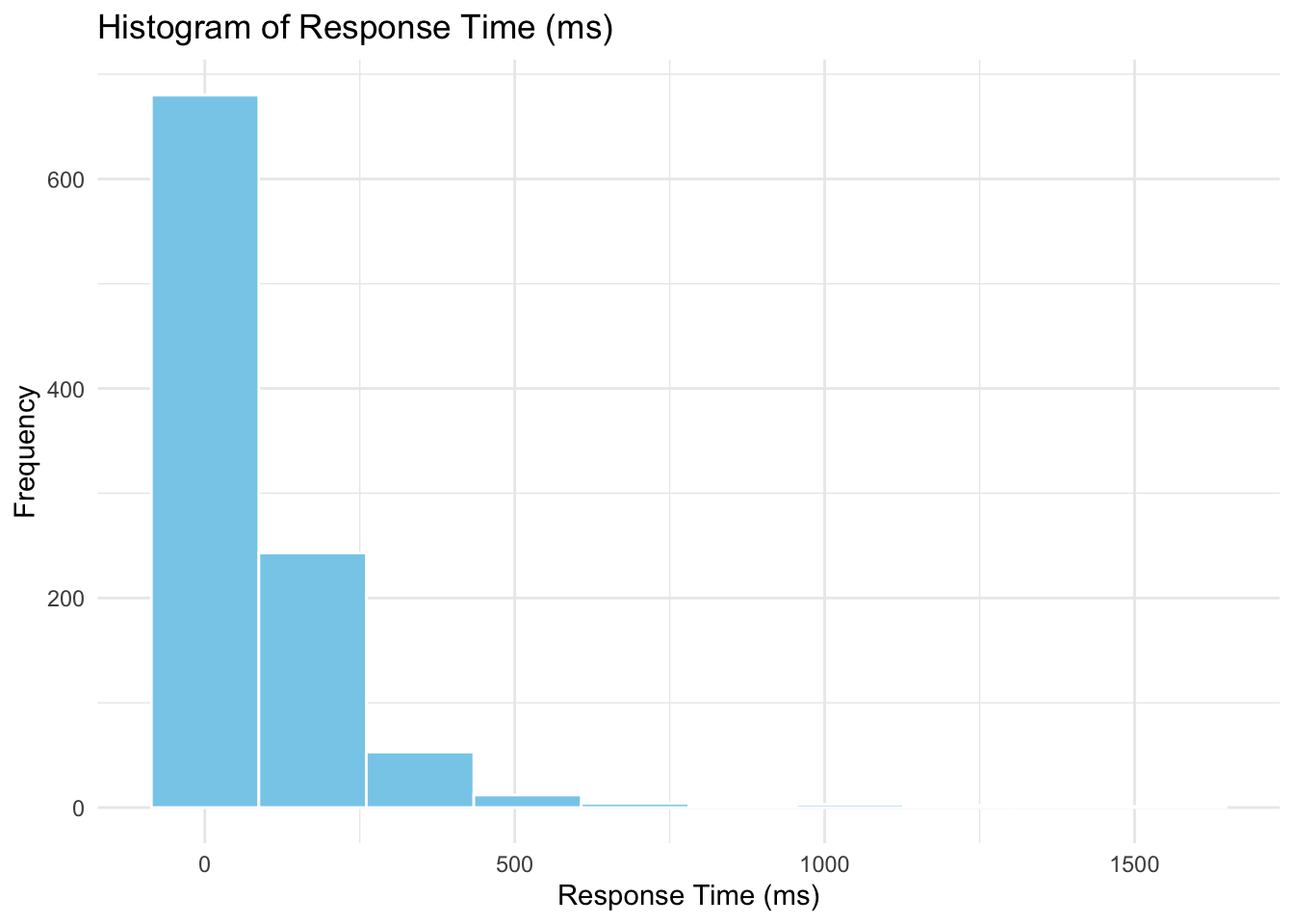

Outliers can distort regression results, so it’s always good practice to check the distribution of the response variable. In our case, we visualize response_time_ms:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

# Histogram of response time

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 5))

sns.histplot(data_encoded["response_time_ms"], bins=30, color="steelblue", edgecolor="white")

plt.title("Distribution of Response Time")

plt.xlabel("Response Time (ms)")

plt.ylabel("Count")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

The histogram confirms that response_time_ms is right-skewed, which aligns with our expectations and supports the use of Gamma regression.

Skewed Data

It’s important to note that with Gamma-distributed data, large values in the upper tail are often part of the natural variation, not necessarily outliers to be removed. Instead of trimming them away, we rely on a model like Gamma regression that is designed to accommodate this skewness.

5. Scaling Continuous Variables (Optional)

Gamma regression does not require predictors to be on the same scale. However, scaling can sometimes help with model convergence and make coefficients easier to interpret, especially when predictors have very different ranges (for example, concurrent_users in the hundreds vs. cache_hit_rate as a percentage).

For this dataset, it may be helpful to standardize the following continuous variables:

concurrent_usersdatabase_queriescache_hit_rateserver_loadmemory_usagetime_of_day

# gamma_server_encoded <- gamma_server_encoded %>%

# mutate(across(c(concurrent_users, database_queries, cache_hit_rate, server_load, memory_usage, time_of_day), scale))# from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

# # List of columns to scale

# scale_cols = ["concurrent_users", "database_queries", "cache_hit_rate", "server_load", "memory_usage", "time_of_day"]

# # Initialize scaler and apply to selected columns

# scaler = StandardScaler()

# data_encoded[scale_cols] = scaler.fit_transform(data_encoded[scale_cols])Standardizing doesn’t change the underlying fit of the Gamma regression, but it can make estimation numerically more stable and the coefficients easier to compare side by side.

After scaling, coefficients are interpreted differently: they now represent the effect of a one-standard-deviation increase in the predictor, rather than a one-unit increase.

Example of Interpretation After Scaling

Without scaling, suppose the coefficient for cache_hit_rate (measured as a percentage from 0–100) is -0.01. This means that for every 1 percentage point increase in cache hit rate, the expected response time decreases slightly.

With scaling, suppose the coefficient for cache_hit_rate becomes -0.25. This means that a one-standard-deviation increase in cache hit rate (say, about 15 percentage points in this dataset) is associated with a 0.25 decrease (on the log scale) in expected response time.

This rescaling doesn’t change the underlying relationship. It just shifts the unit of interpretation from “1 raw unit” to “1 standard deviation,” which often makes cross-variable comparisons more meaningful.

For simplicity, we will not scale the variables in this case study, but it’s a useful option to keep in mind.

A Note on Data Splitting

In many machine learning tasks, it is common to split the data into training and test sets. However, in this case study, we are not aiming to build a predictive model. Our goal is to understand how different server and request characteristics influence the average response time, which is an inferential task.

Because we are focused on interpreting the model rather than predicting new outcomes, we will use the entire dataset for model fitting. This allows us to make the best use of our data when estimating the effects of each variable.

If our goal were to build a model that predicts server response time for future requests, we would consider splitting the dataset and evaluating prediction accuracy on a holdout set.

4.9 Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA)

The data is now ready and cleaned, but before we begin modeling, it is essential to explore the dataset to understand the structure of the variables and how they relate to one another. This step, known as Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA), helps uncover patterns, identify potential issues such as skewness or outliers, and inform the modeling decisions that follow.

4.9.1 Classifying Variables

A good starting point in EDA is to classify the variables in our dataset, as this guides the choice of plots and informs how we will encode each variable when building the model.

Our response variable is:

-

response_time_ms: a continuous, strictly positive variable measuring how long a server takes to respond to a request. This is well-suited for Gamma regression.

Our regressors fall into two groups:

-

Continuous variables:

-

concurrent_users,database_queries,cache_hit_rate,server_load,memory_usage,time_of_day

-

-

Categorical variables:

-

cdn_usage,request_complexity,day_of_week,geographic_region

-

4.9.2 Visualizing Variable Distributions

With the variables classified, we can now choose appropriate plots to explore their distributions and relationships.

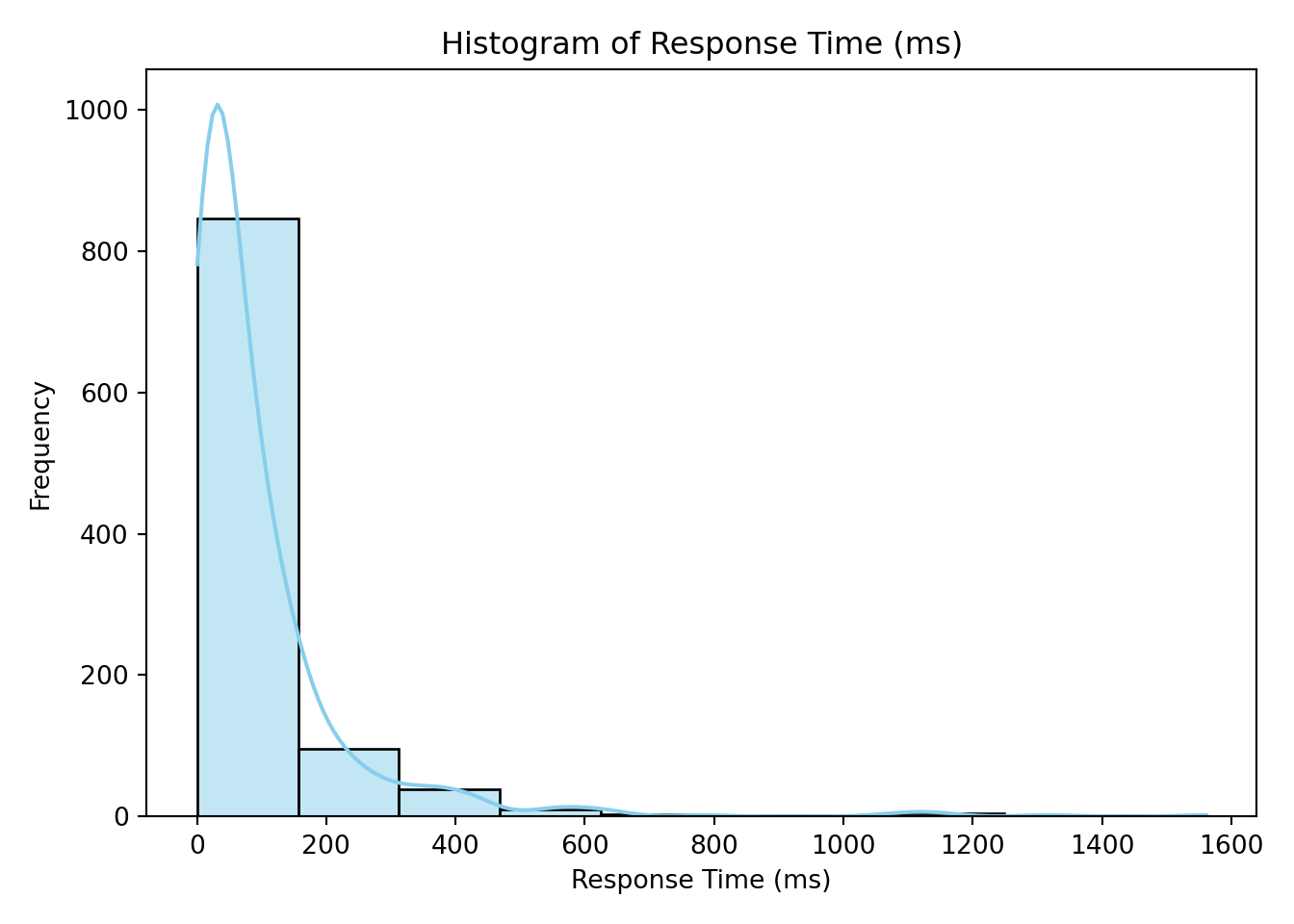

Response Variable: response_time_ms

We begin by examining the distribution of the response variable.

library(ggplot2)

ggplot(gamma_server_encoded, aes(x = response_time_ms)) +

geom_histogram(bins = 10, fill = "skyblue", color = "white") +

labs(title = "Histogram of Response Time (ms)",

x = "Response Time (ms)",

y = "Frequency") +

theme_minimal()

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

sns.histplot(data_encoded["response_time_ms"], bins=10, kde=True, color="skyblue")

plt.title("Histogram of Response Time (ms)")

plt.xlabel("Response Time (ms)")

plt.ylabel("Frequency")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

The histogram confirms that response_time_ms is strictly positive and right-skewed—just as we saw during data wrangling when we checked for negative values and visualized potential outliers.

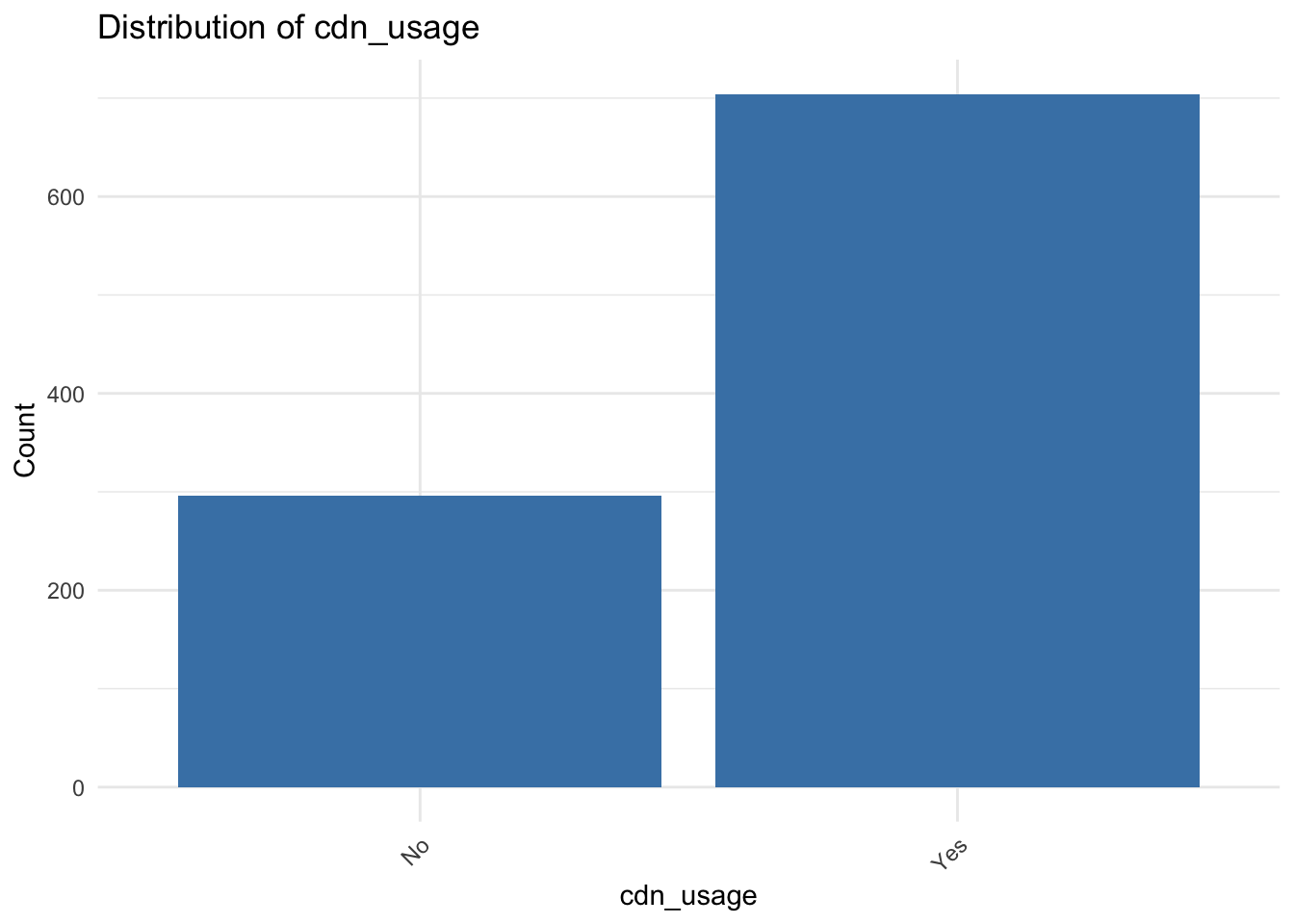

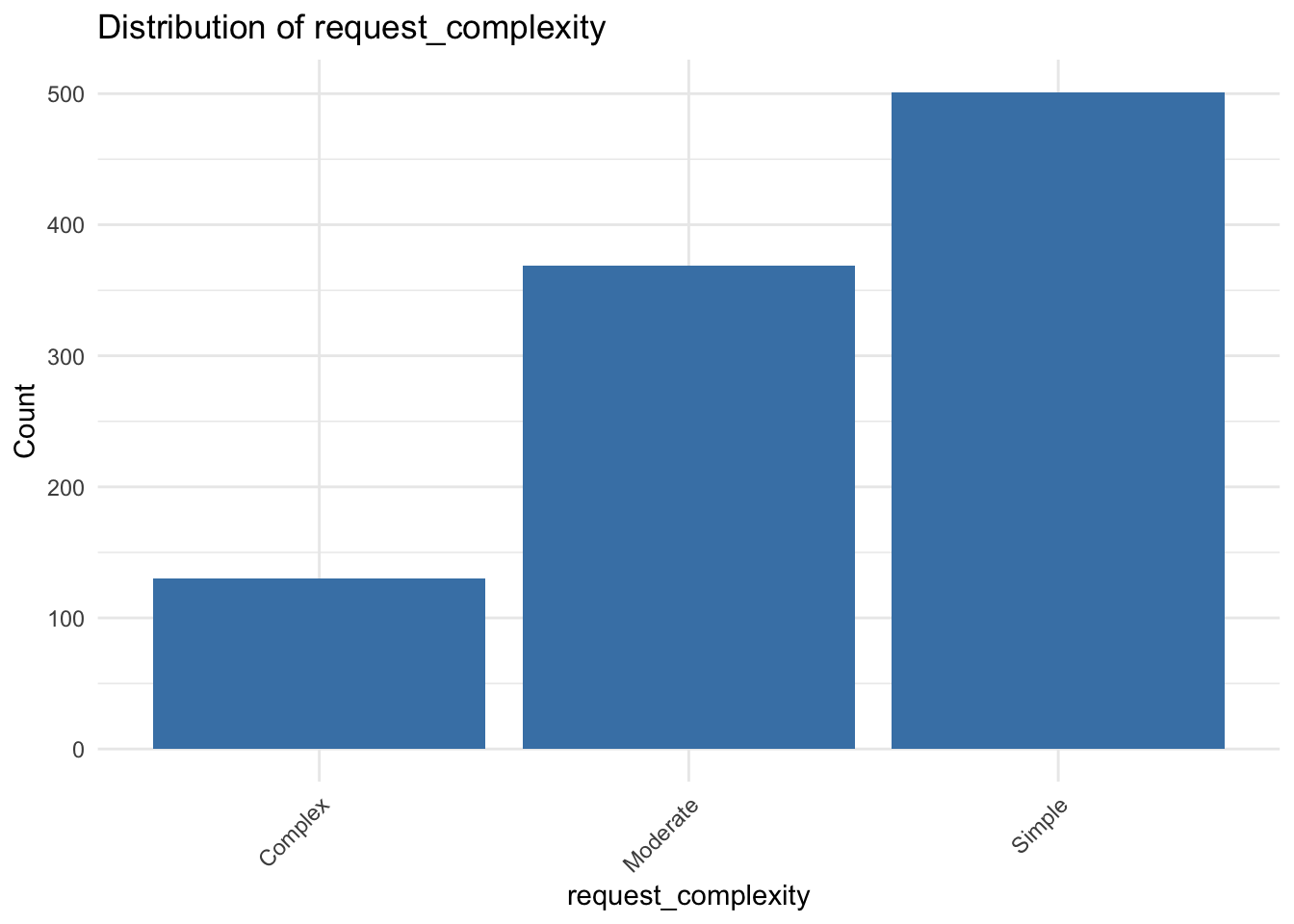

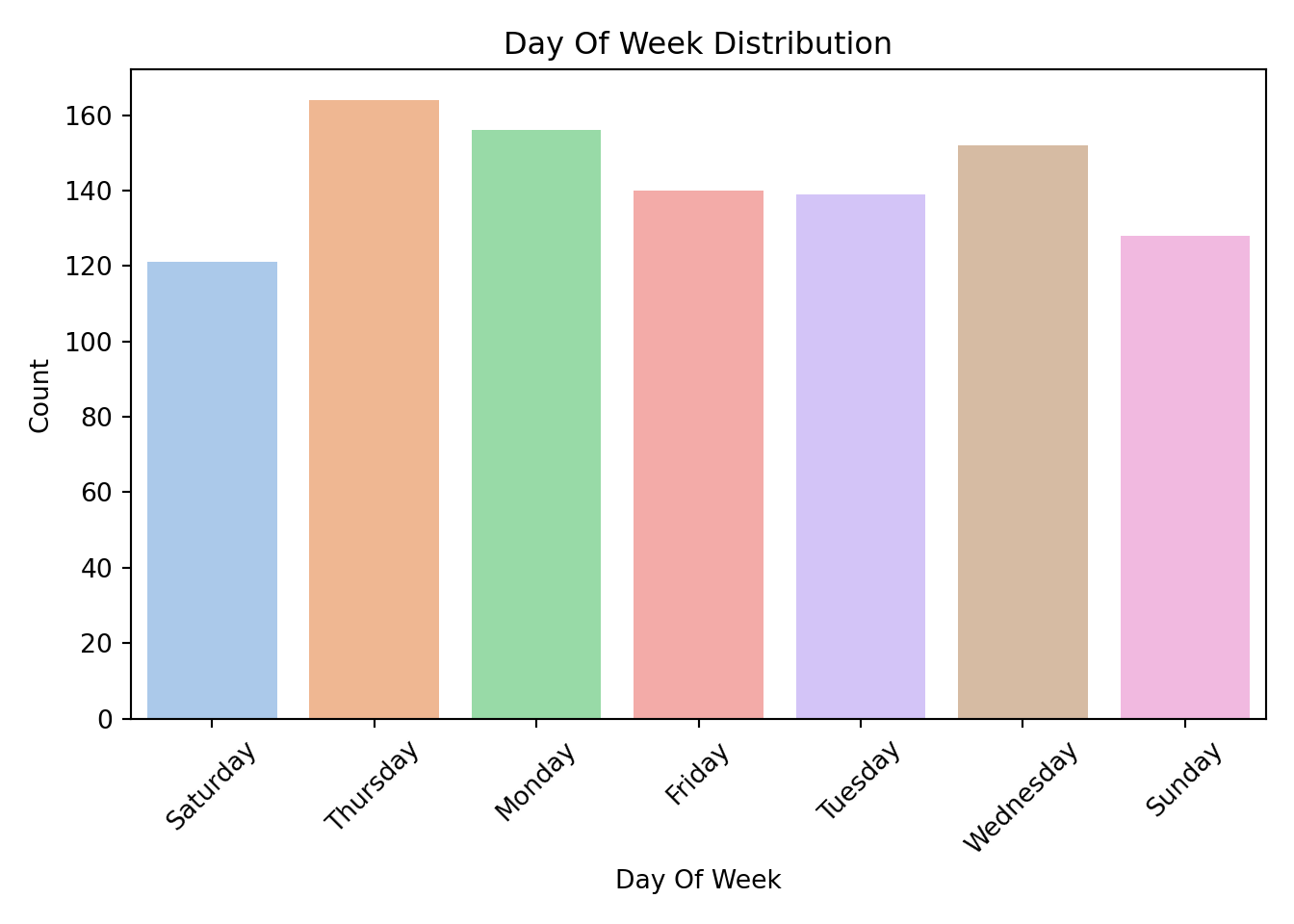

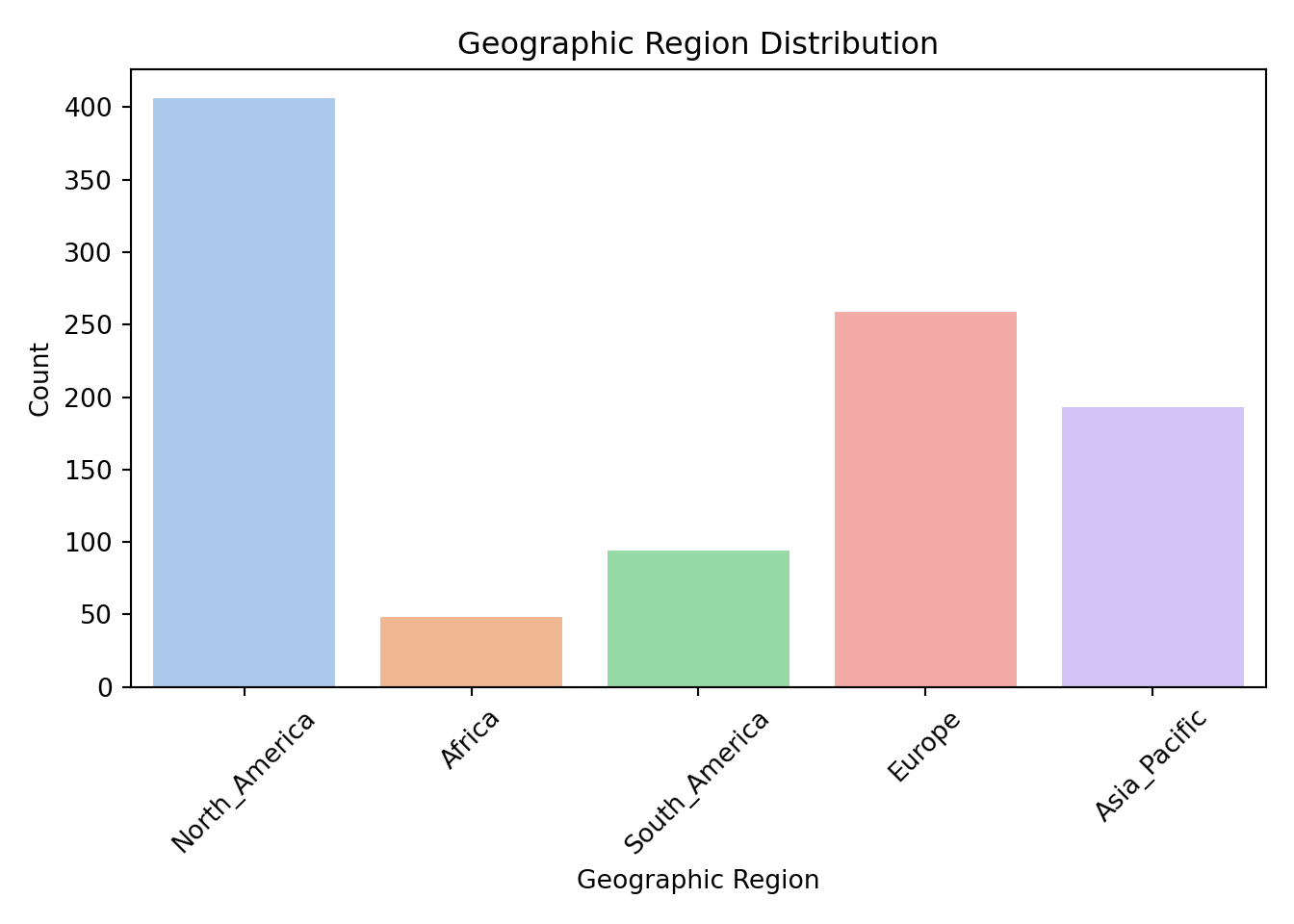

Categorical Variables

We next examine how the categorical predictors are distributed. This visualization is based on the original dataset, before encoding. Visualizing these variables helps us check if any levels are underrepresented or imbalanced, which can affect model stability and interpretation.

library(ggplot2)

categorical_vars <- c("cdn_usage", "request_complexity", "day_of_week", "geographic_region")

for (var in categorical_vars) {

p <- ggplot(gamma_server, aes(x = .data[[var]])) +

geom_bar(fill = "steelblue") +

labs(

title = paste("Distribution of", var),

x = var,

y = "Count"

) +

theme_minimal() +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 45, hjust = 1))

print(p)

}

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

categorical_vars = ["cdn_usage", "request_complexity", "day_of_week", "geographic_region"]

for var in categorical_vars:

sns.countplot(

x=var,

data=data,

hue=var,

palette="pastel",

legend=False

)

plt.title(f"{var.replace('_', ' ').title()} Distribution")

plt.xlabel(var.replace("_", " ").title())

plt.ylabel("Count")

plt.xticks(rotation=45)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()<Axes: xlabel='cdn_usage', ylabel='count'>

Text(0.5, 1.0, 'Cdn Usage Distribution')

Text(0.5, 0, 'Cdn Usage')

Text(0, 0.5, 'Count')

([0, 1], [Text(0, 0, 'Yes'), Text(1, 0, 'No')])

<Axes: xlabel='request_complexity', ylabel='count'>

Text(0.5, 1.0, 'Request Complexity Distribution')

Text(0.5, 0, 'Request Complexity')

Text(0, 0.5, 'Count')

([0, 1, 2], [Text(0, 0, 'Moderate'), Text(1, 0, 'Complex'), Text(2, 0, 'Simple')])

<Axes: xlabel='day_of_week', ylabel='count'>

Text(0.5, 1.0, 'Day Of Week Distribution')

Text(0.5, 0, 'Day Of Week')

Text(0, 0.5, 'Count')

([0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6], [Text(0, 0, 'Saturday'), Text(1, 0, 'Thursday'), Text(2, 0, 'Monday'), Text(3, 0, 'Friday'), Text(4, 0, 'Tuesday'), Text(5, 0, 'Wednesday'), Text(6, 0, 'Sunday')])

<Axes: xlabel='geographic_region', ylabel='count'>

Text(0.5, 1.0, 'Geographic Region Distribution')

Text(0.5, 0, 'Geographic Region')

Text(0, 0.5, 'Count')

([0, 1, 2, 3, 4], [Text(0, 0, 'North_America'), Text(1, 0, 'Africa'), Text(2, 0, 'South_America'), Text(3, 0, 'Europe'), Text(4, 0, 'Asia_Pacific')])

By examining these distributions, we can ensure that each category has enough observations to be meaningfully included in the model. If a category is rarely observed, it may need to be combined with others or omitted.

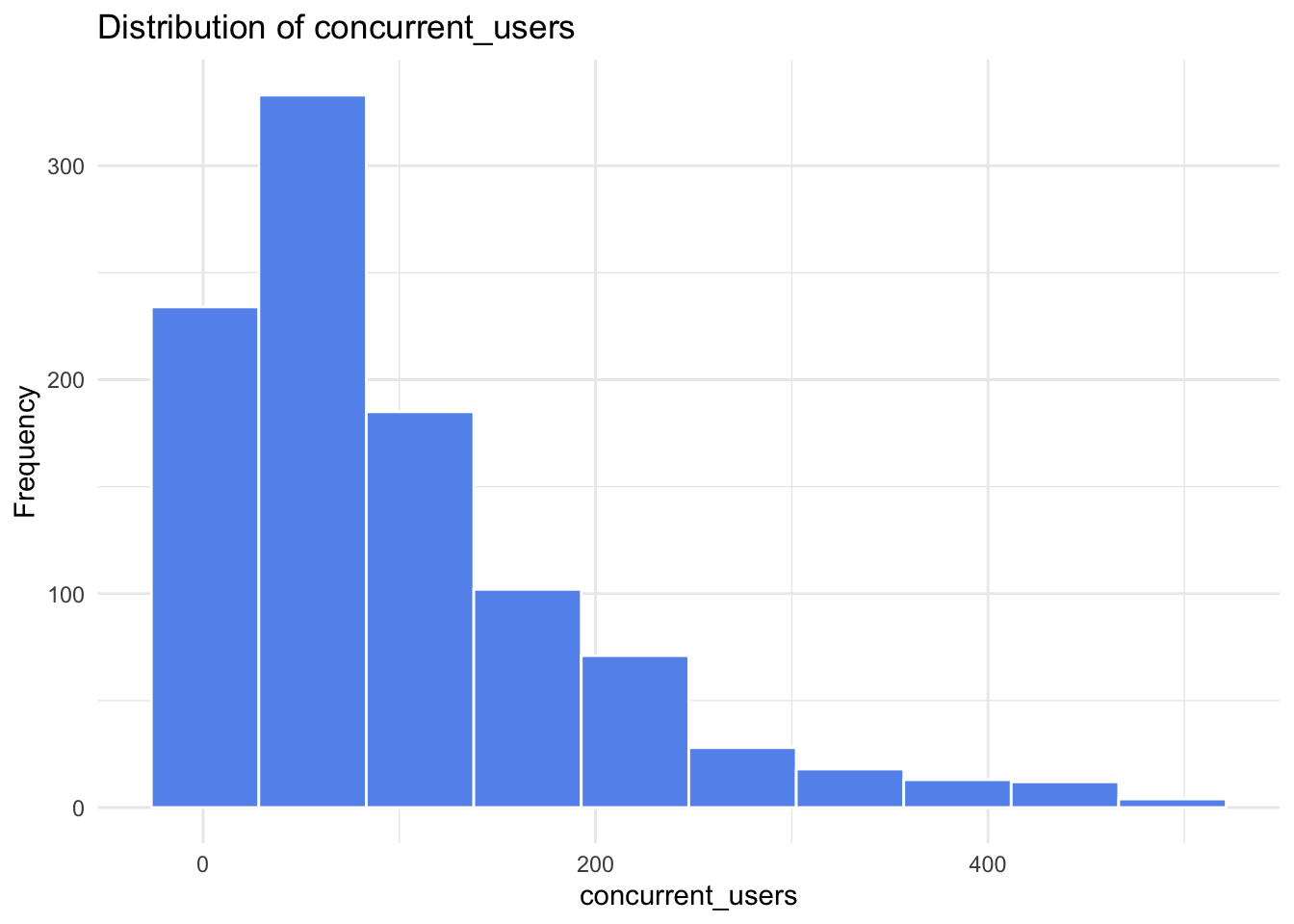

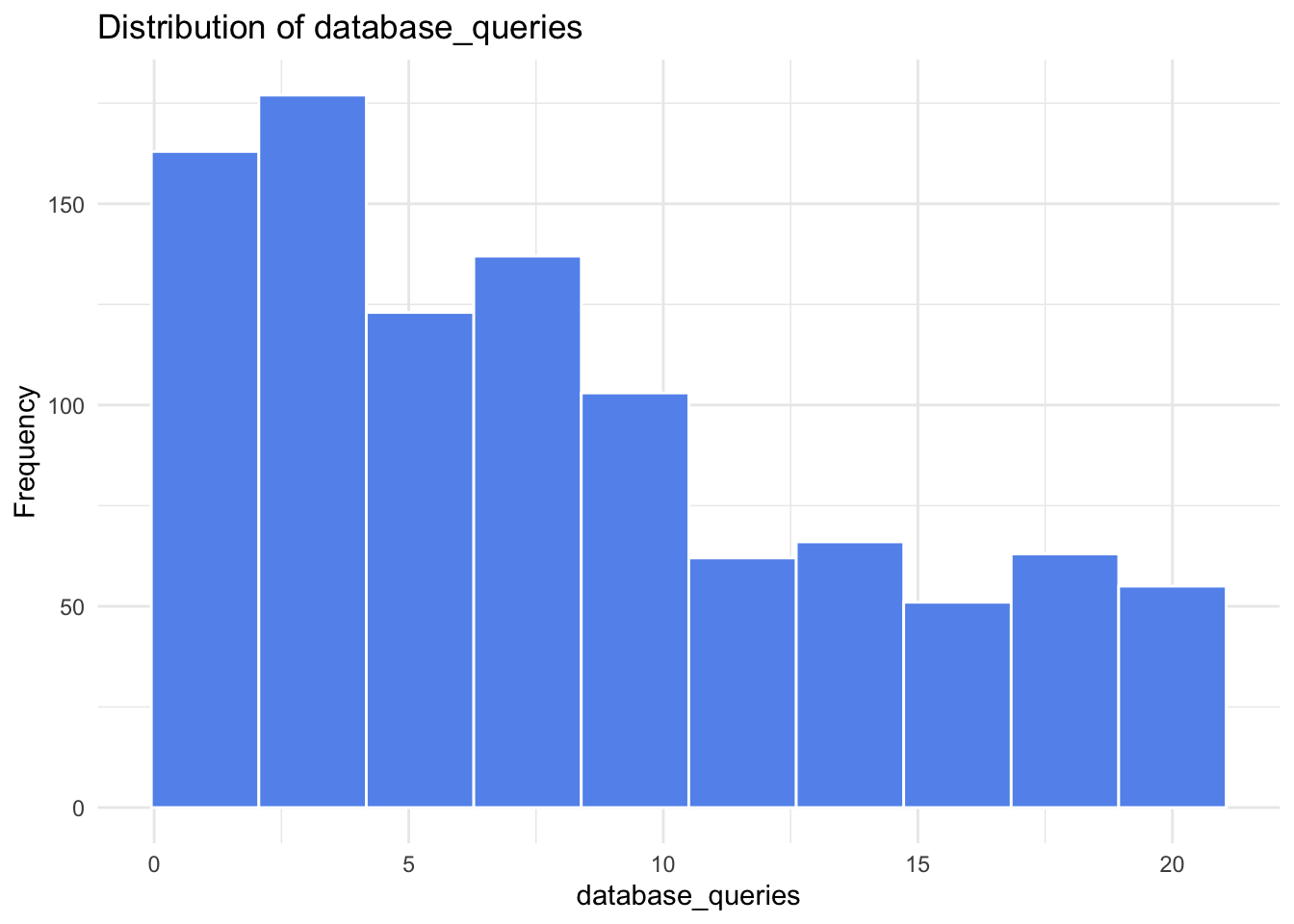

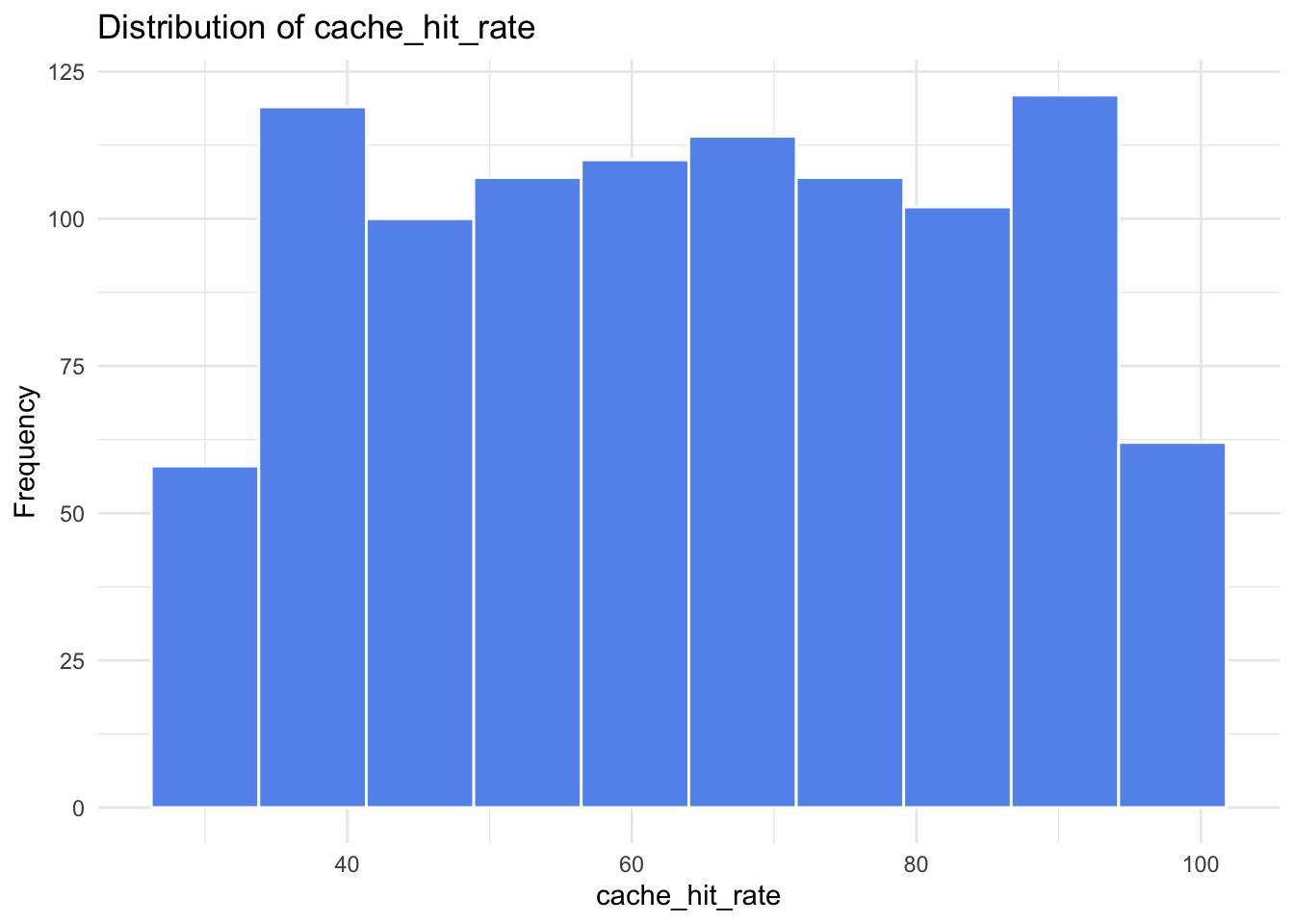

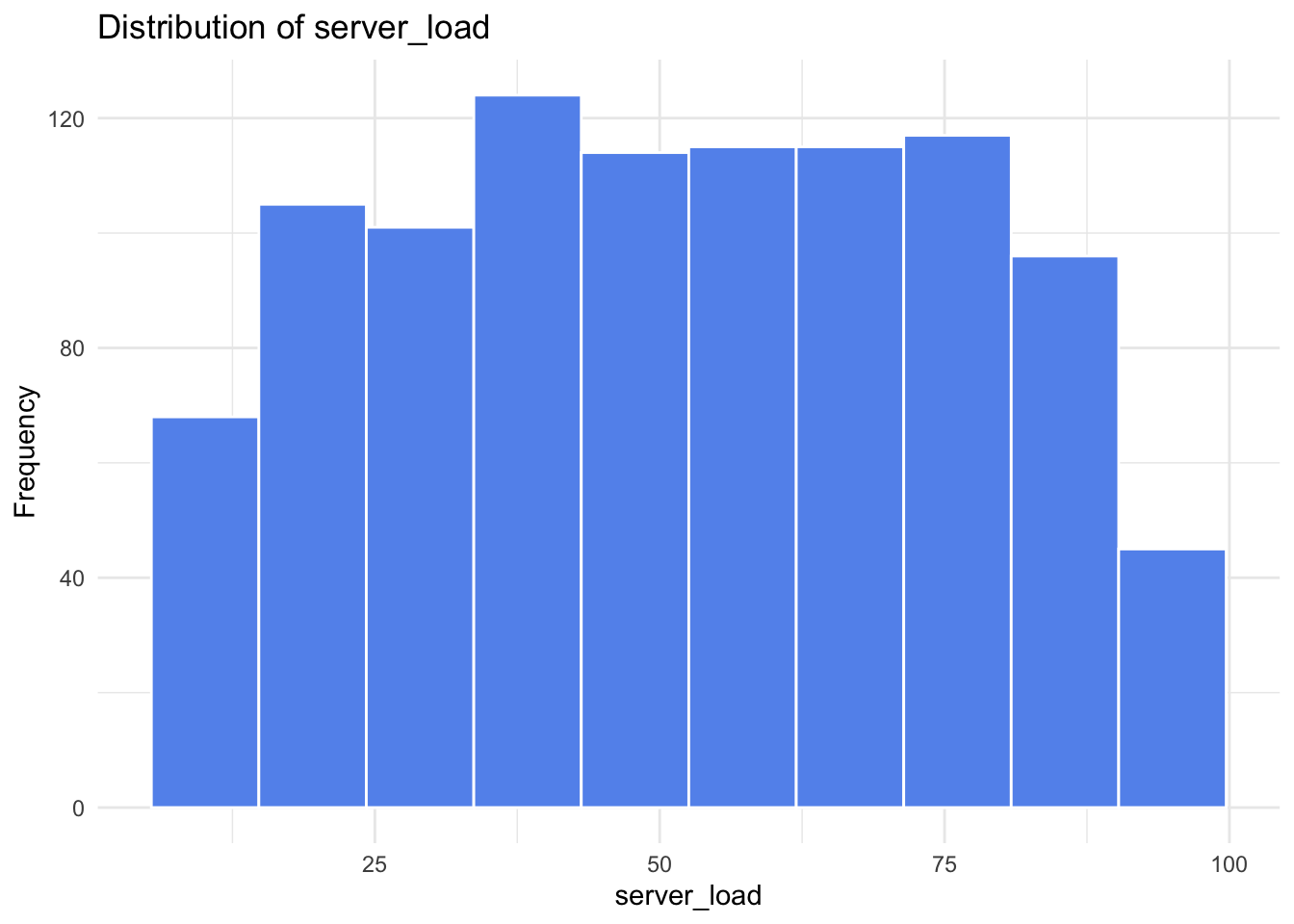

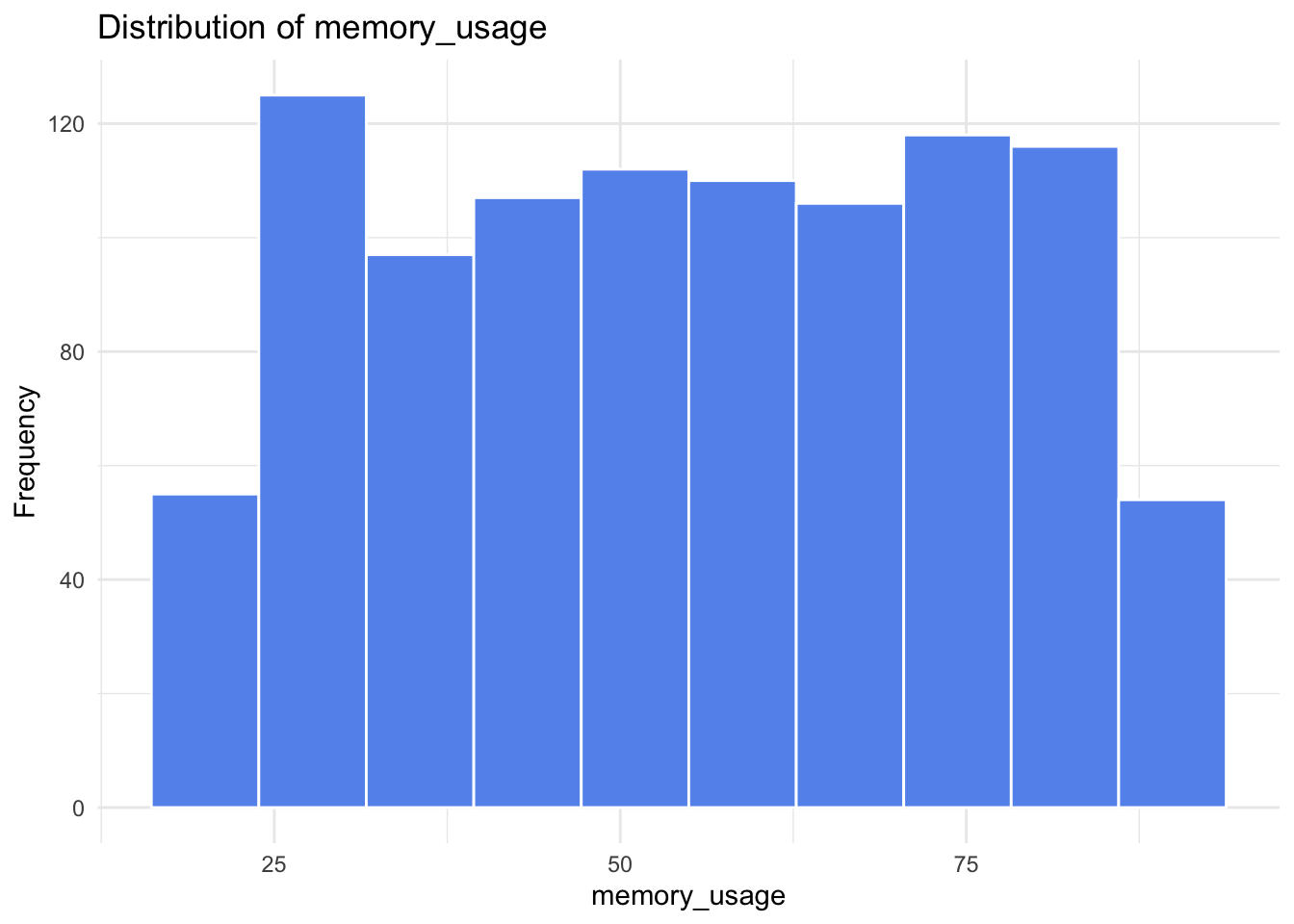

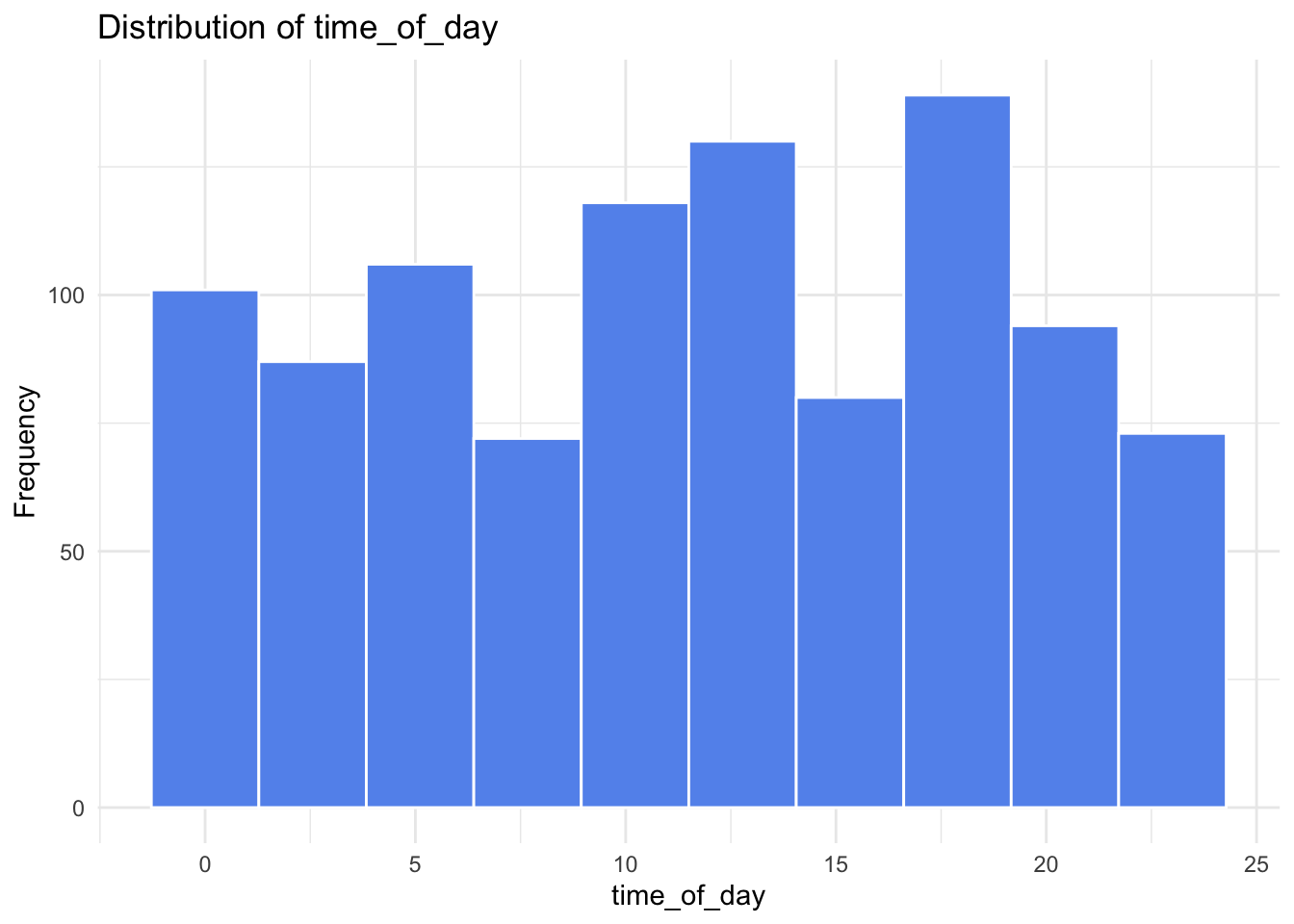

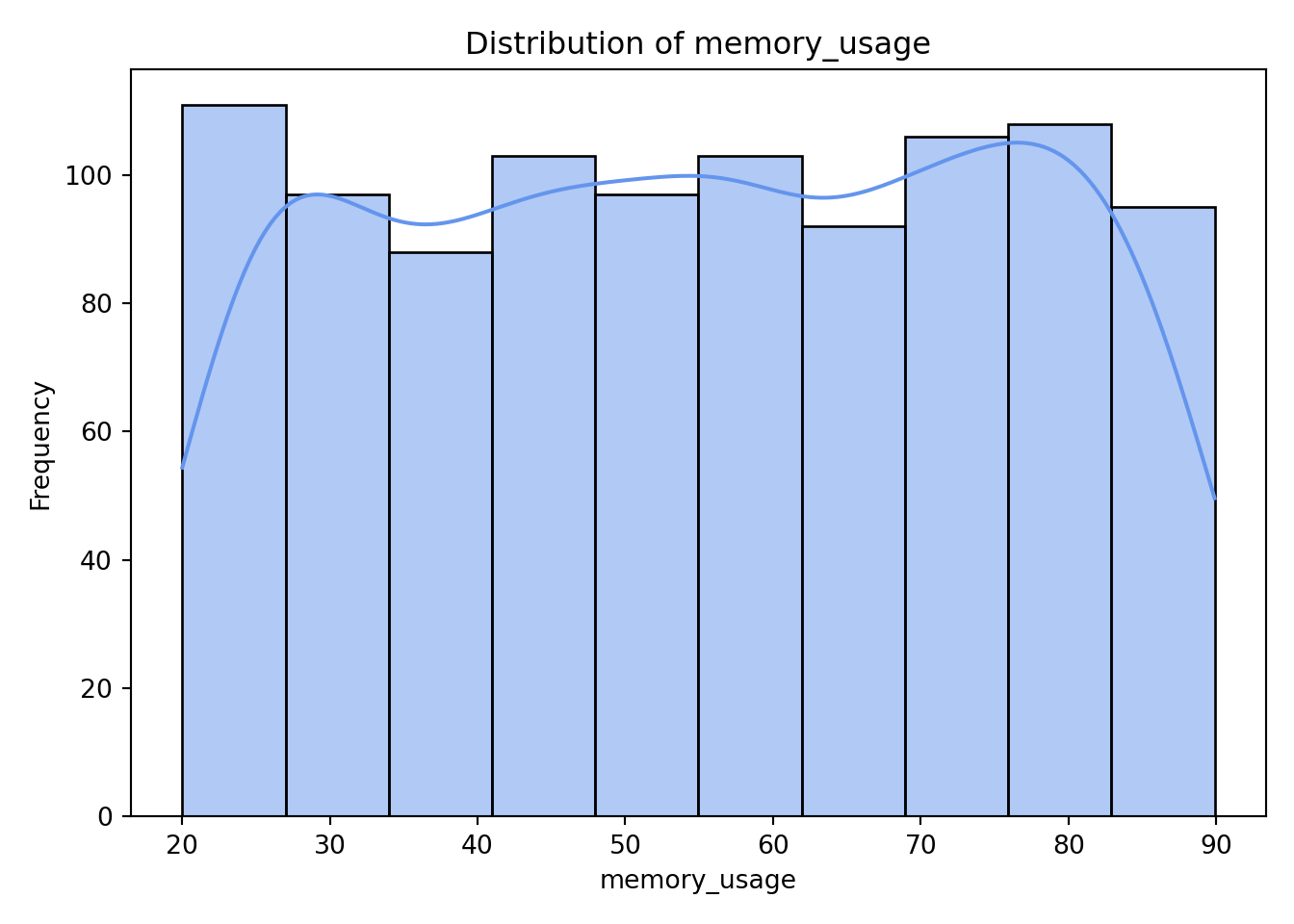

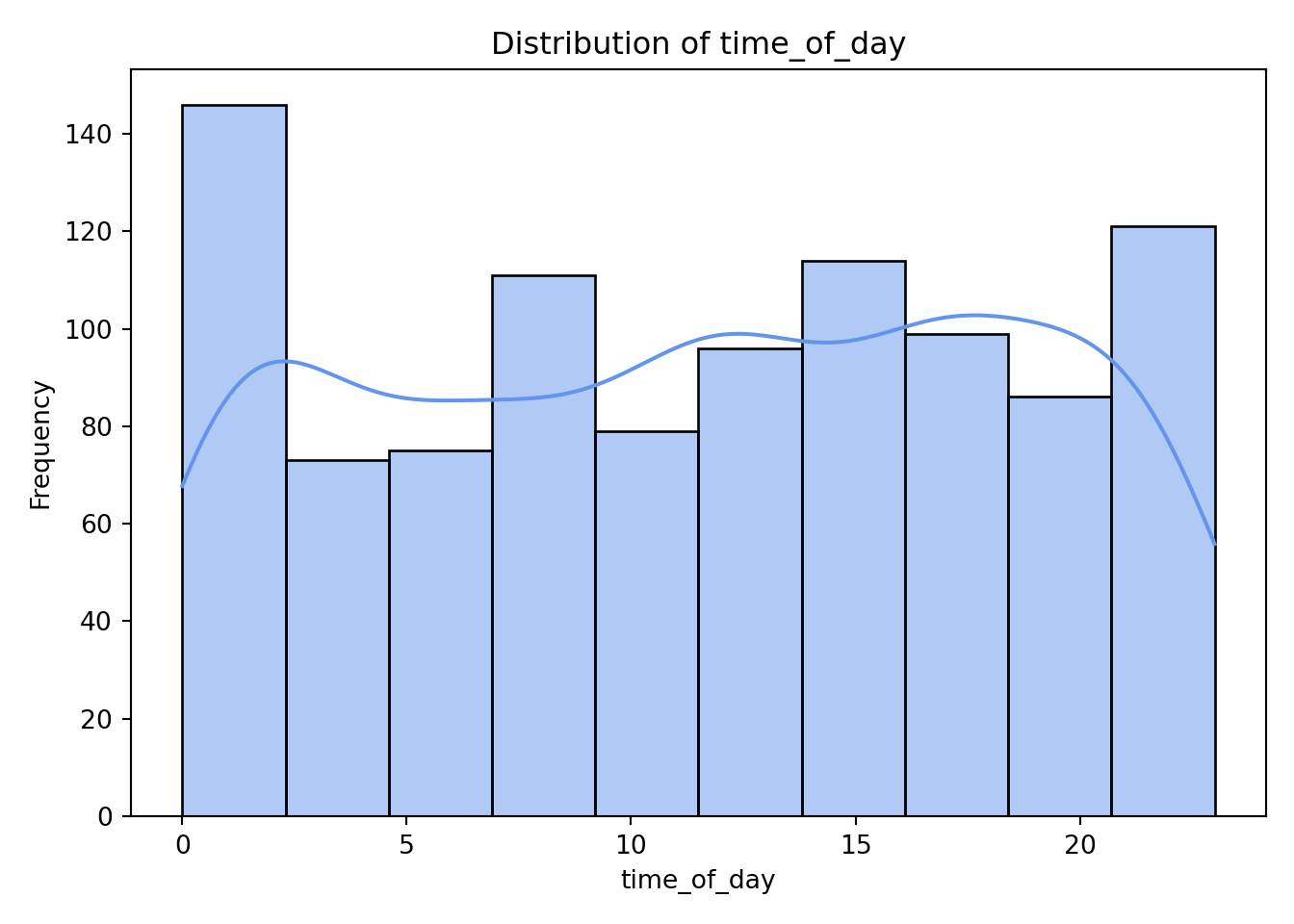

Numerical Variables

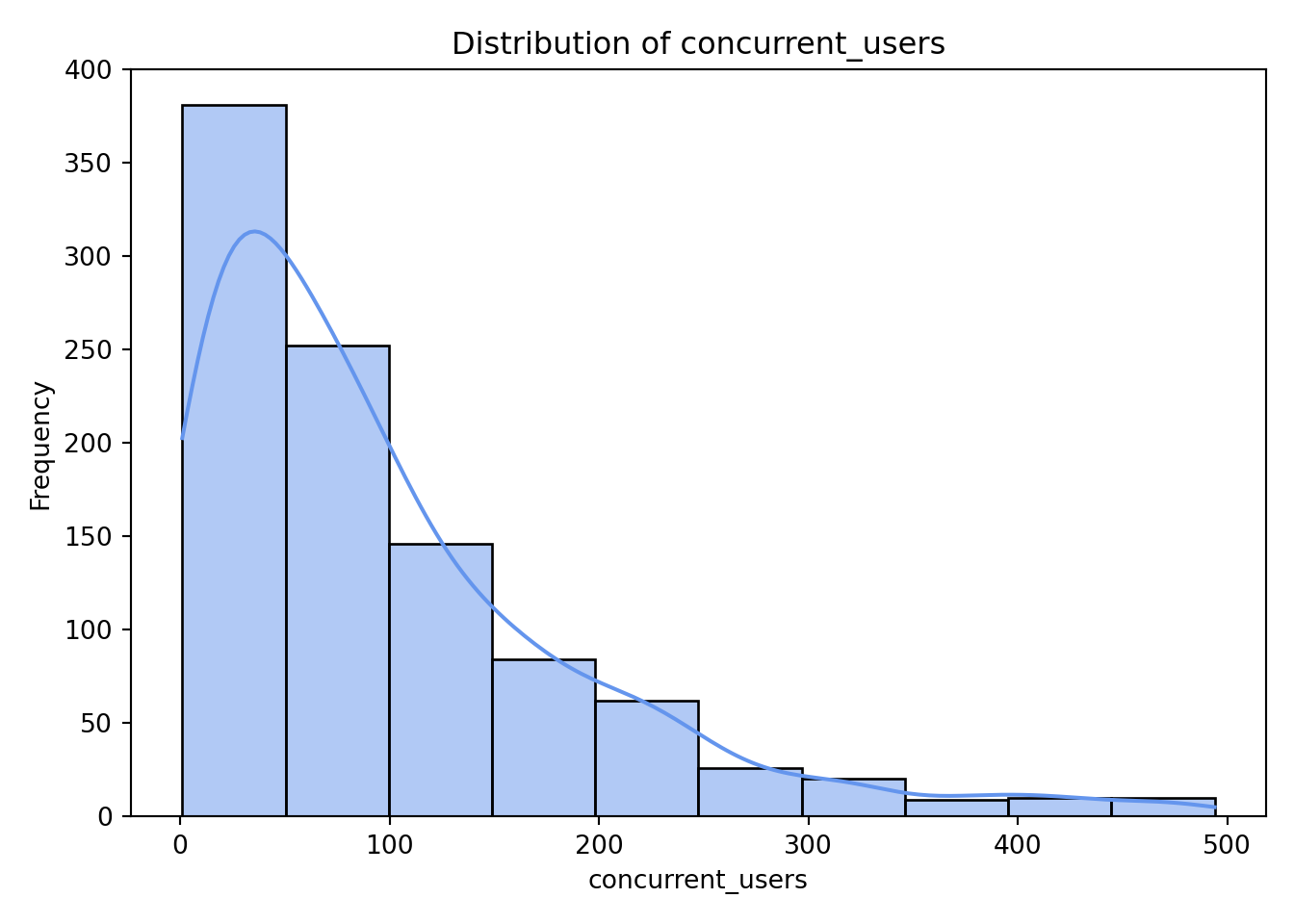

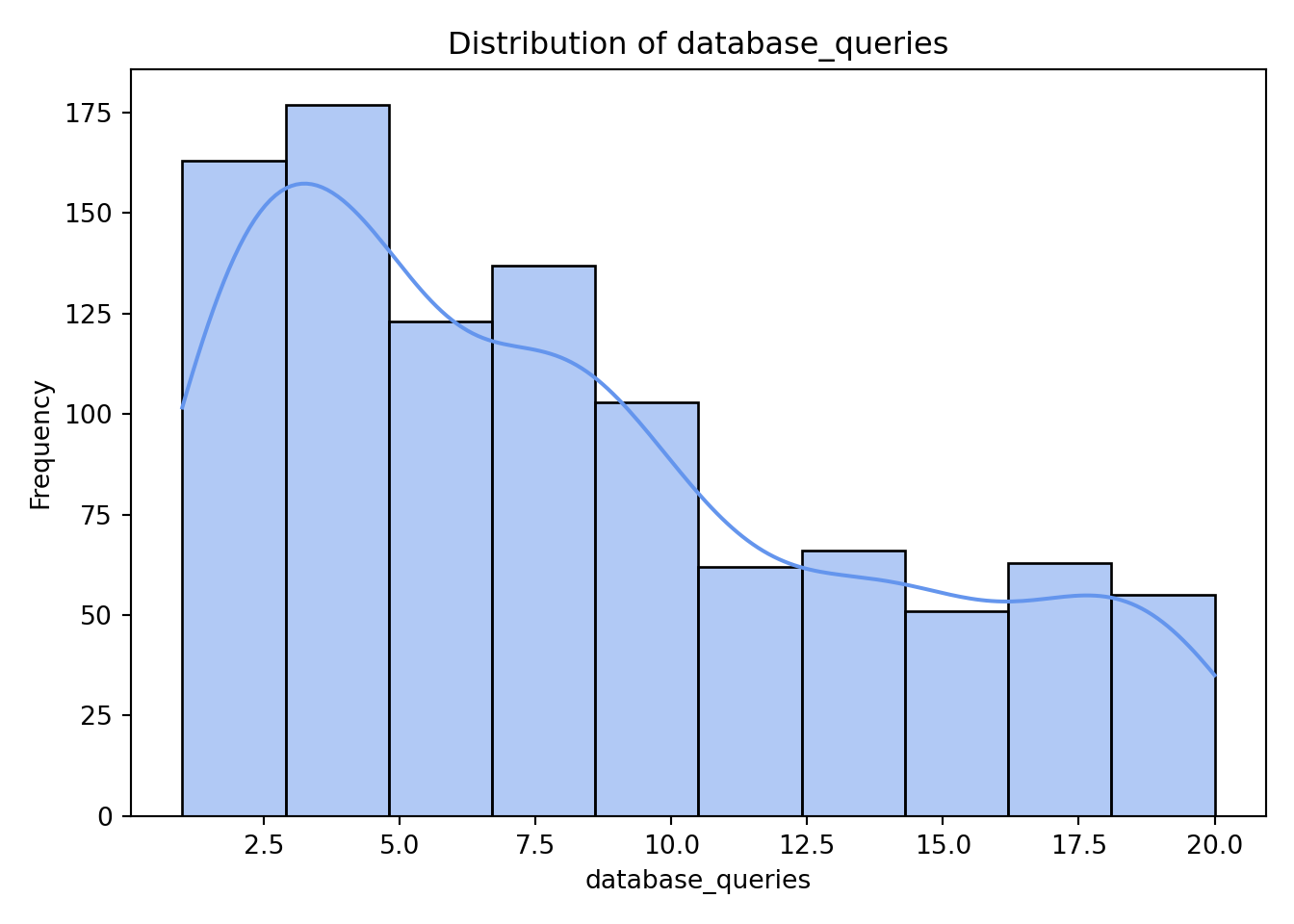

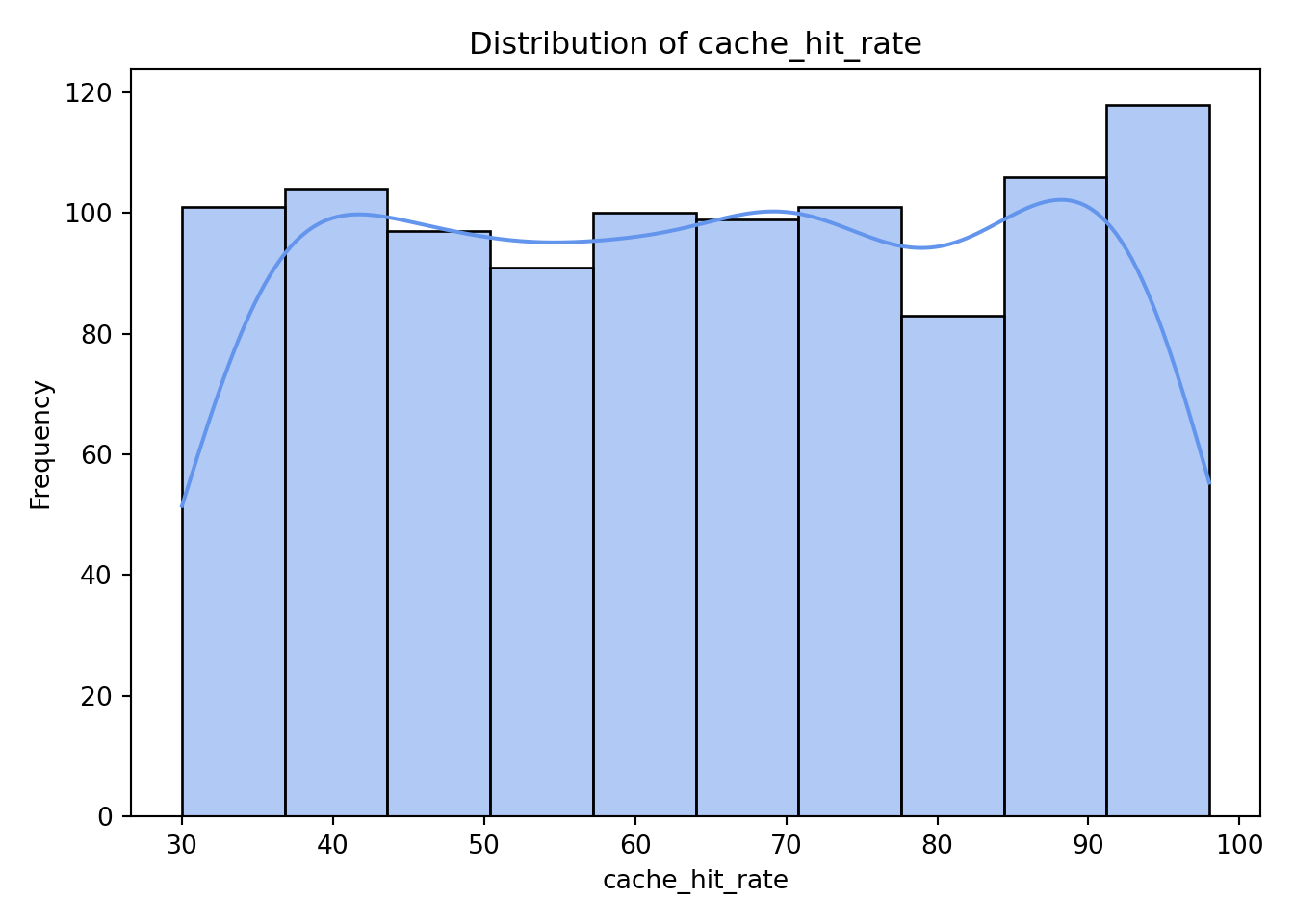

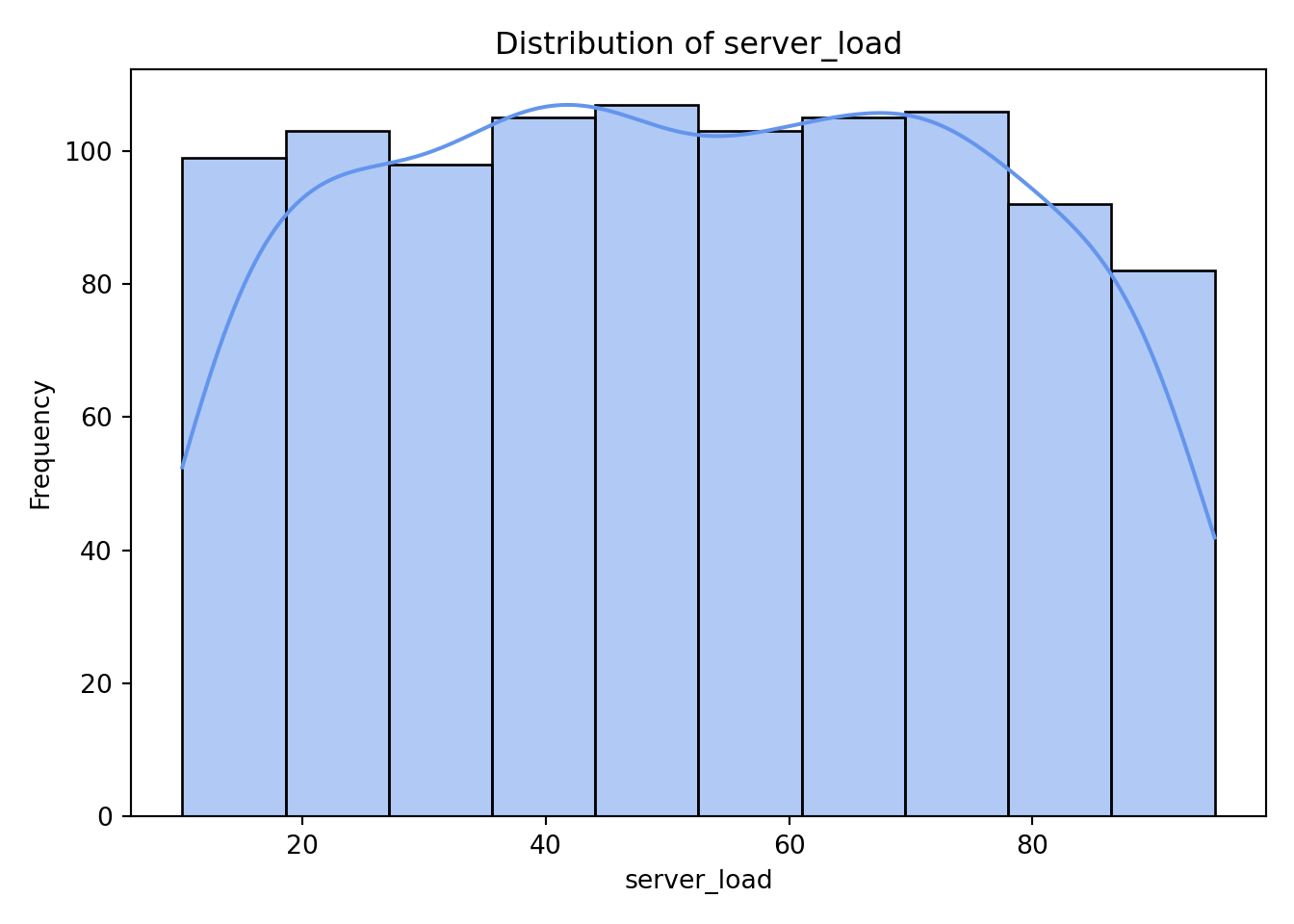

Next, we examine the distributions of the continuous predictors to understand their range, shape, and potential skewness.

library(ggplot2)

continuous_vars <- c(

"concurrent_users", "database_queries", "cache_hit_rate",

"server_load", "memory_usage", "time_of_day"

)

for (var in continuous_vars) {

p <- ggplot(gamma_server, aes(x = .data[[var]])) +

geom_histogram(bins = 10, fill = "cornflowerblue", color = "white") +

labs(

title = paste("Distribution of", var),

x = var,

y = "Frequency"

) +

theme_minimal()

print(p)

}

continuous_vars = ["concurrent_users", "database_queries", "cache_hit_rate", "server_load", "memory_usage", "time_of_day"]

for var in continuous_vars:

sns.histplot(data[var], bins=10, kde=True, color="cornflowerblue")

plt.title(f"Distribution of {var}")

plt.xlabel(var)

plt.ylabel("Frequency")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

As we can see from the histograms, nothing appears too concerning. Both concurrent_users and database_queries show clear right-skewness, while the remaining continuous variables have more uniform or evenly spread distributions. memory_usage shows a lower count in its final (largest) bin, but this pattern is not unusual and does not raise any major concerns for our analysis.

4.9.3 Visualizing Predictor Relationships to Response

Having explored the univariate distributions, we can now turn to bivariate visualizations to examine how each predictor relates to the response.

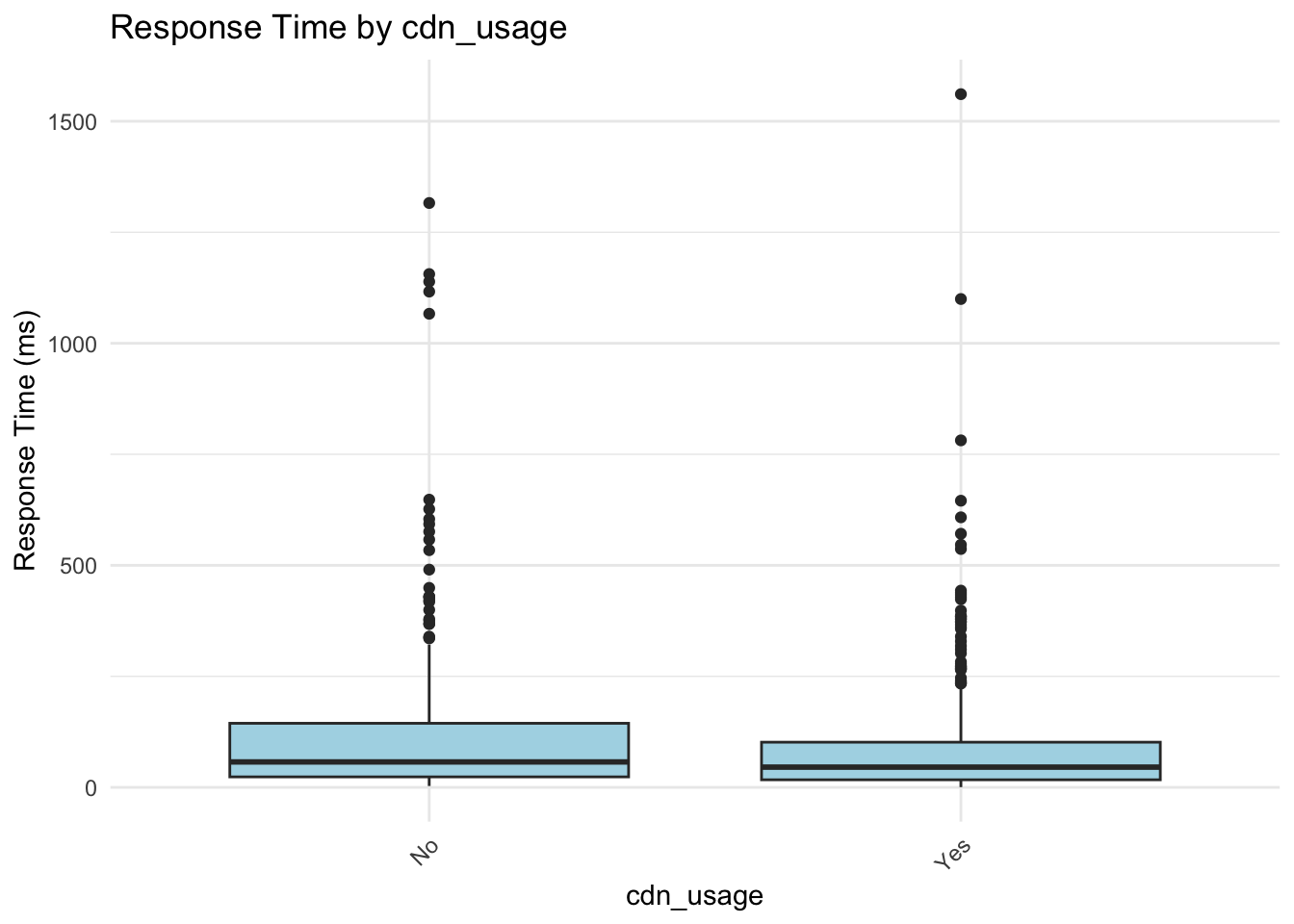

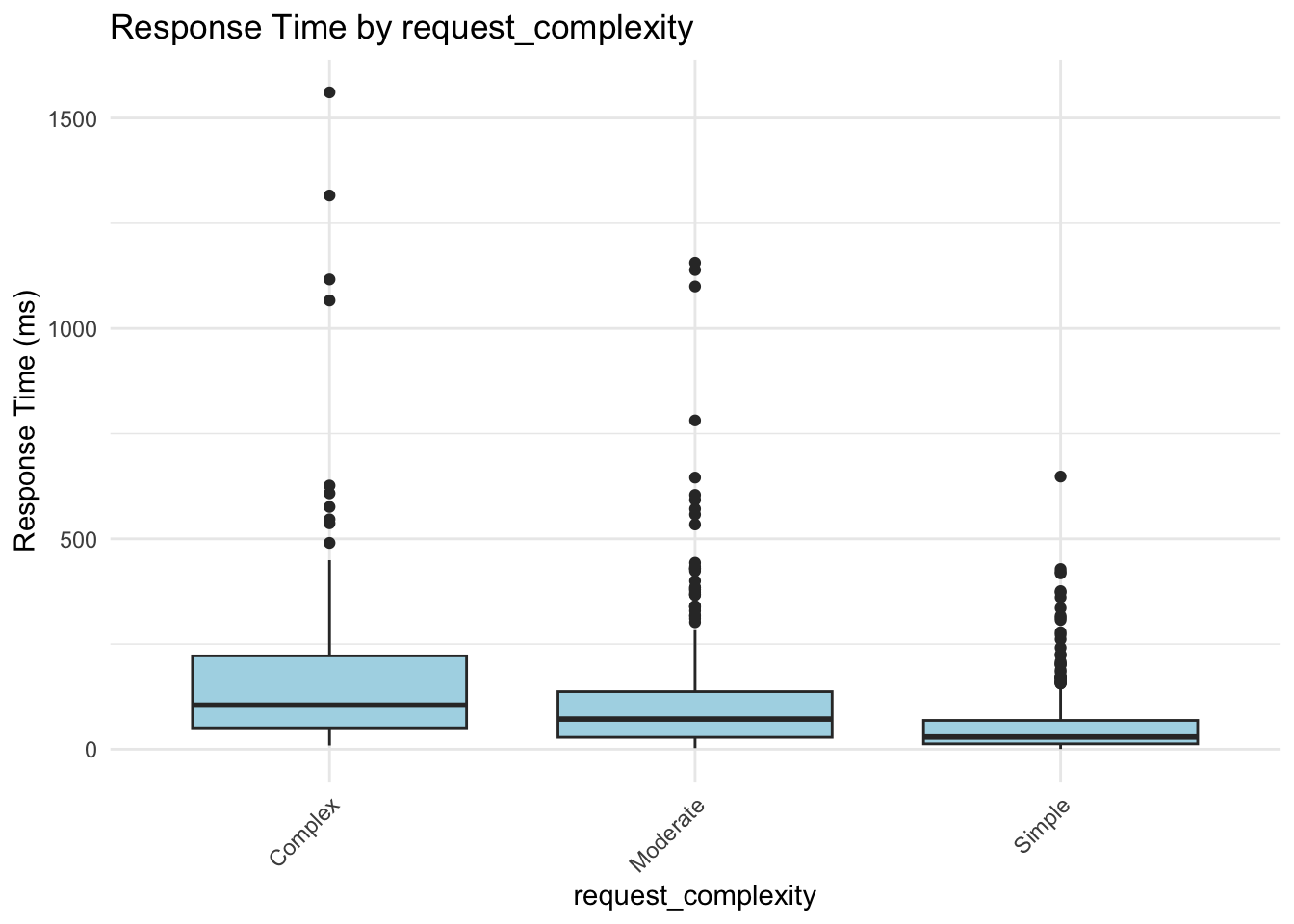

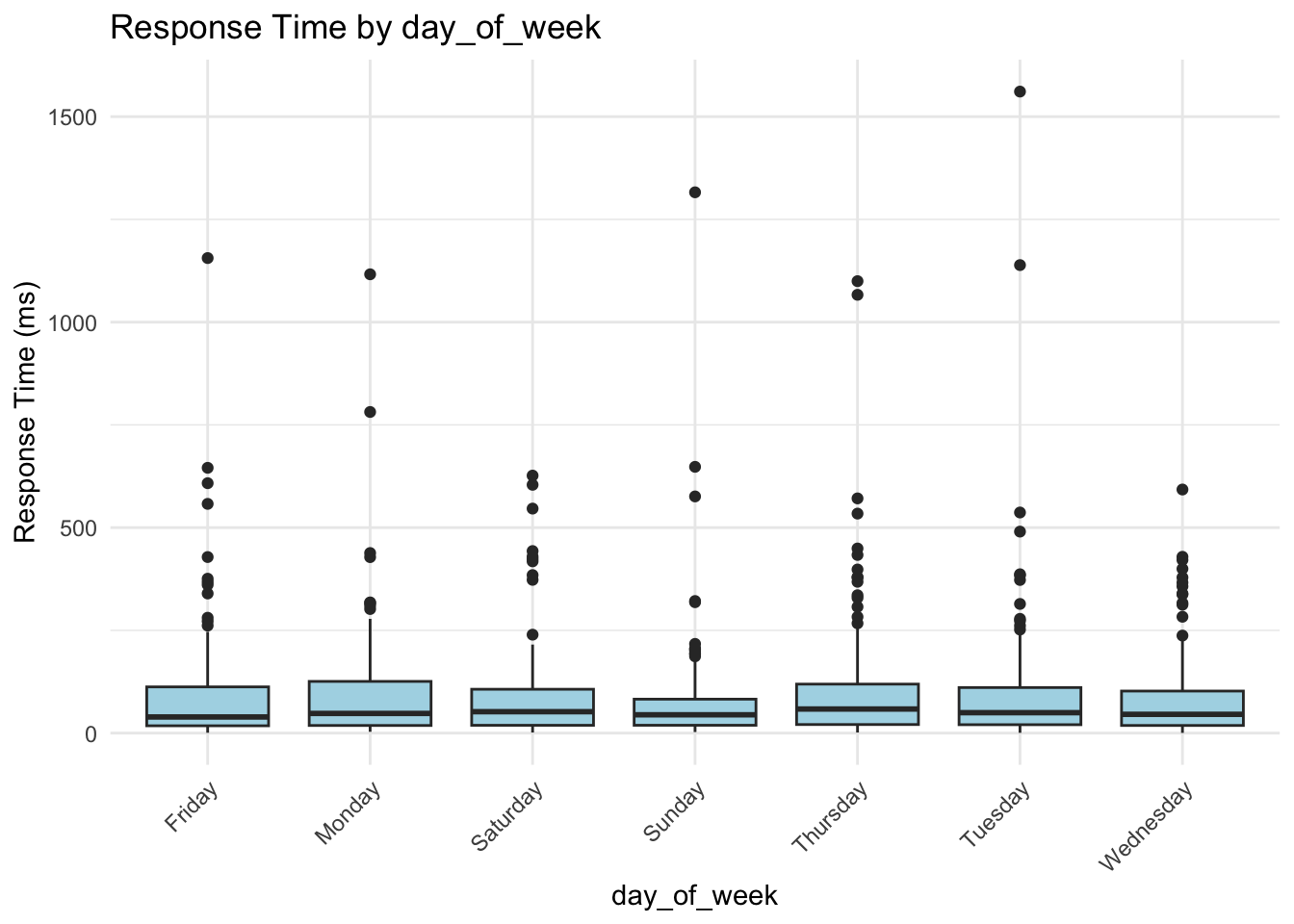

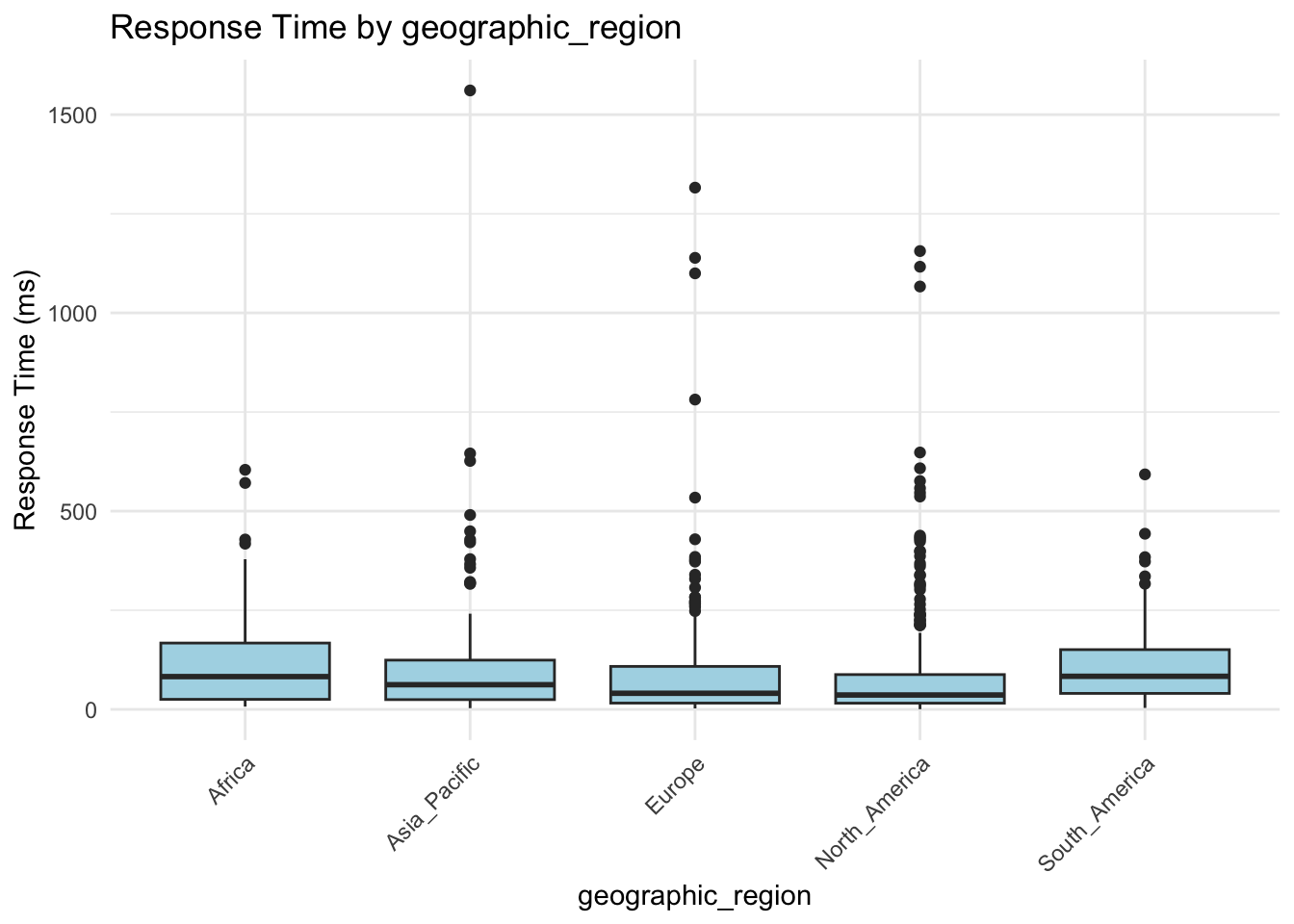

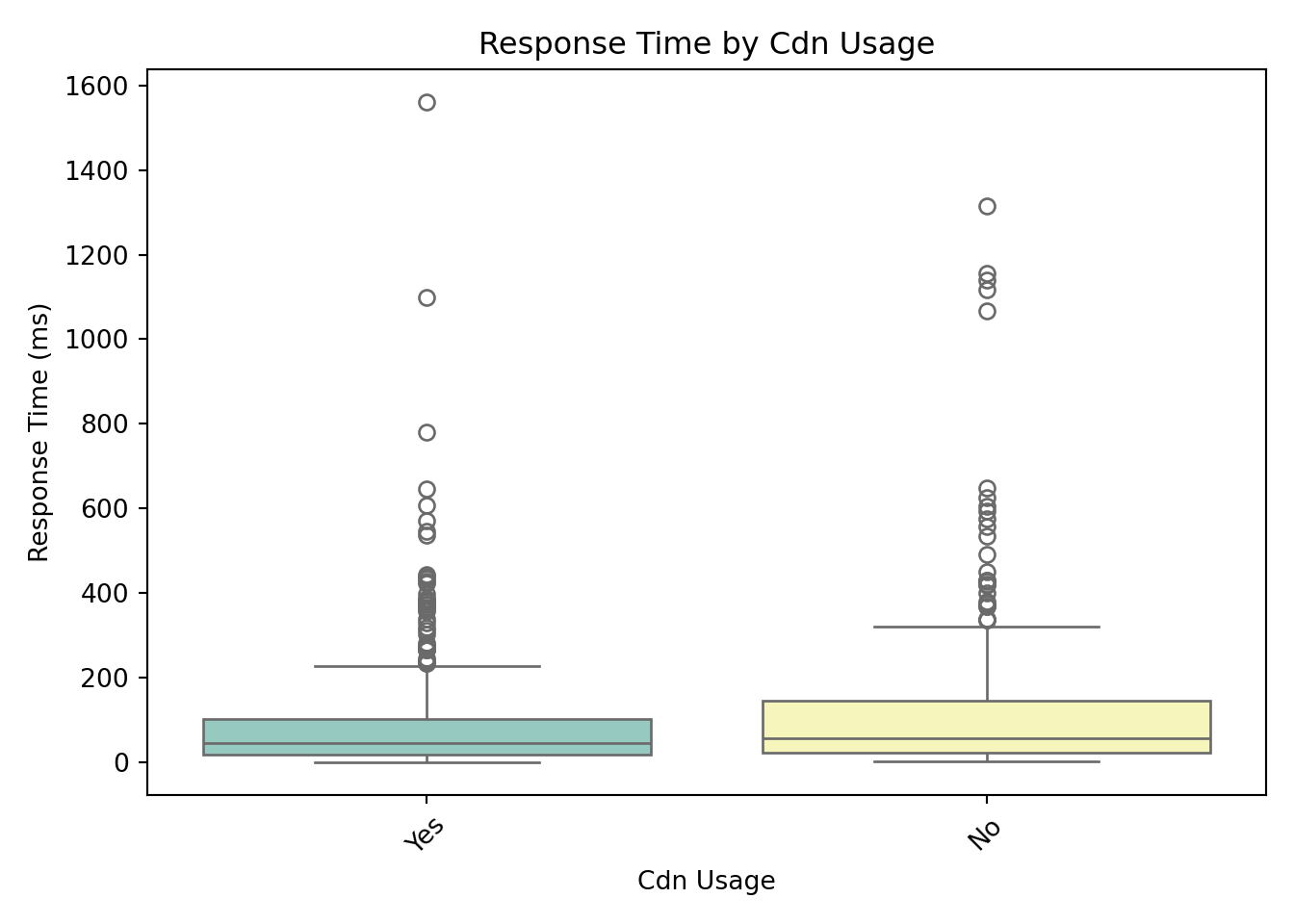

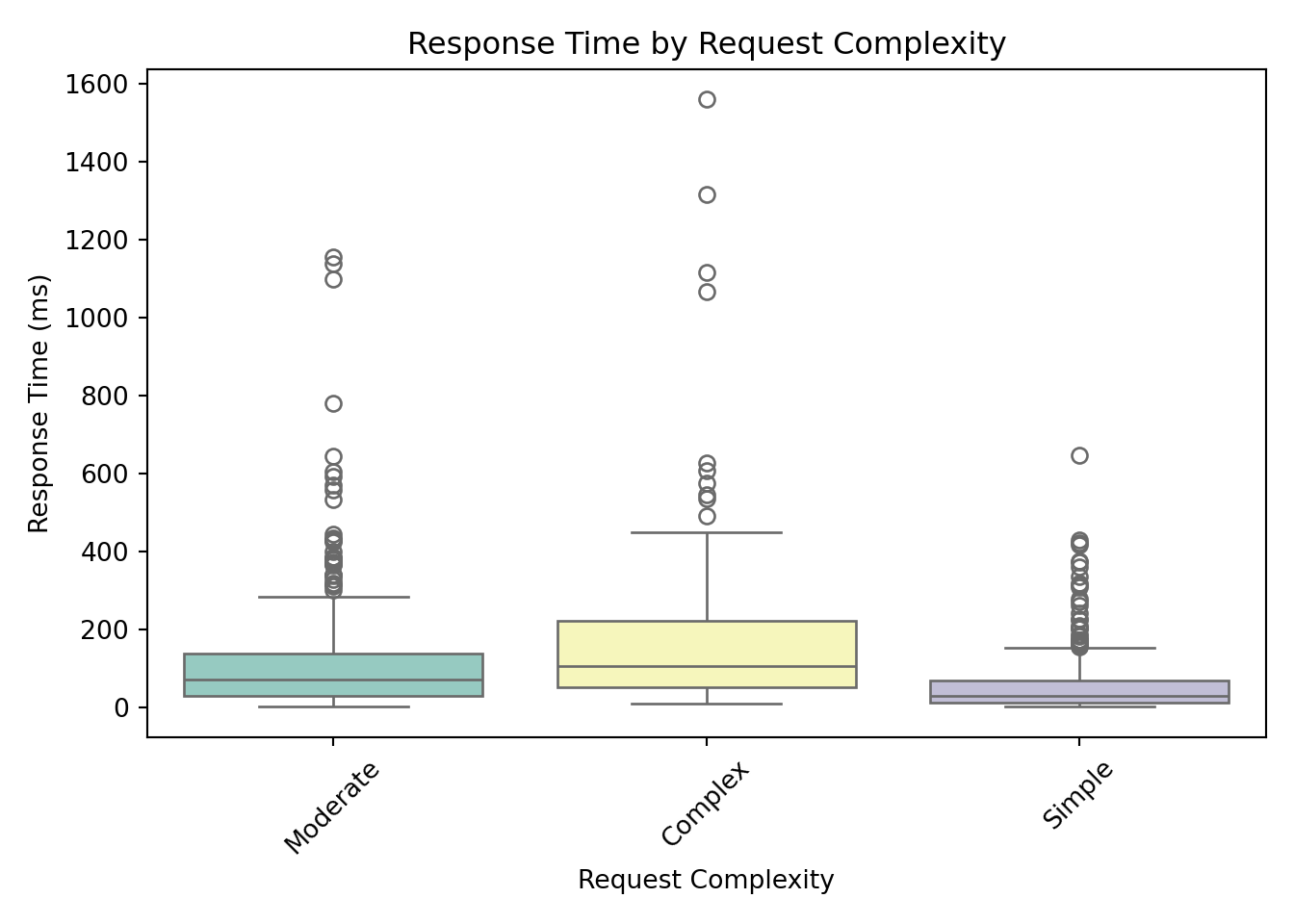

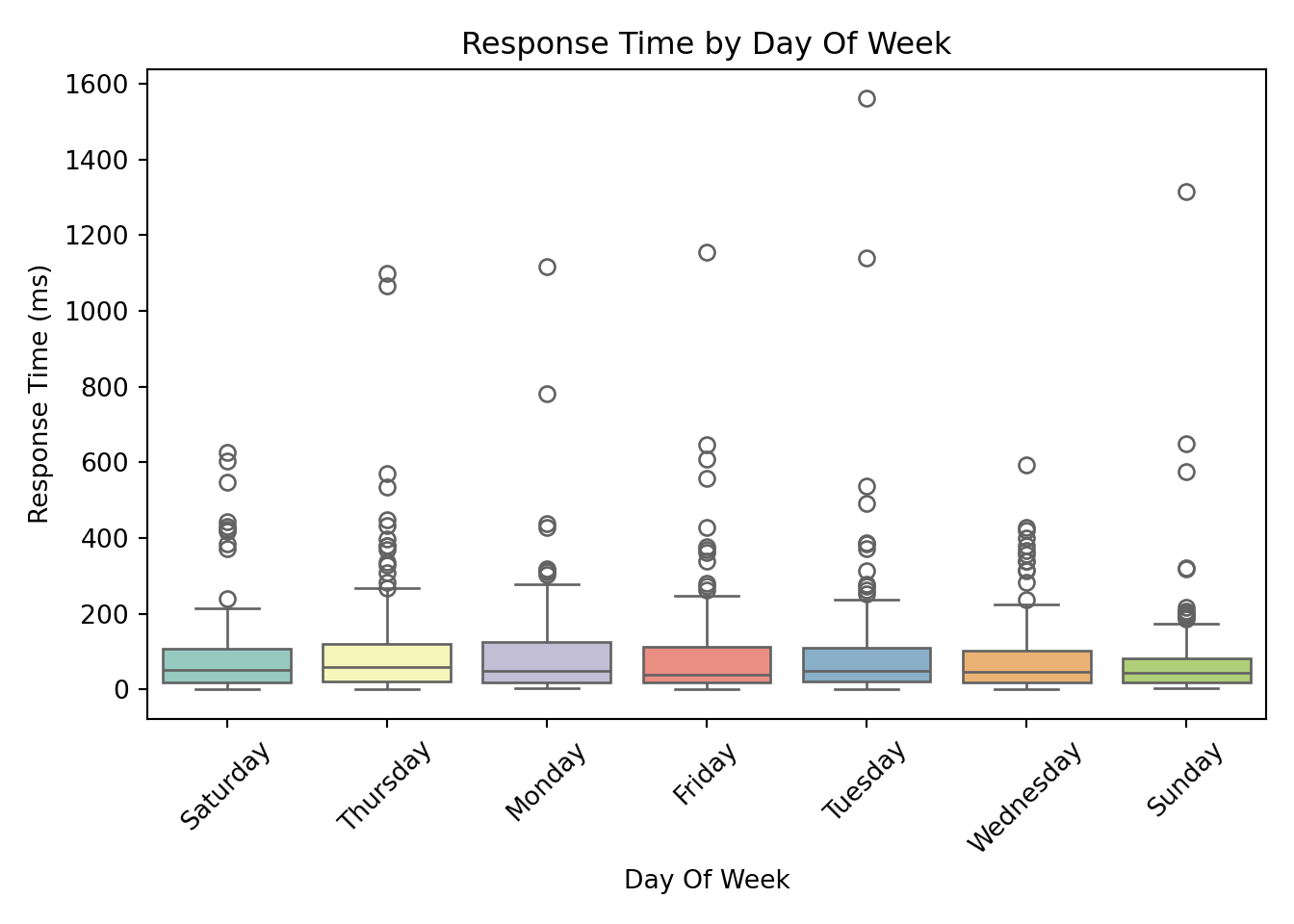

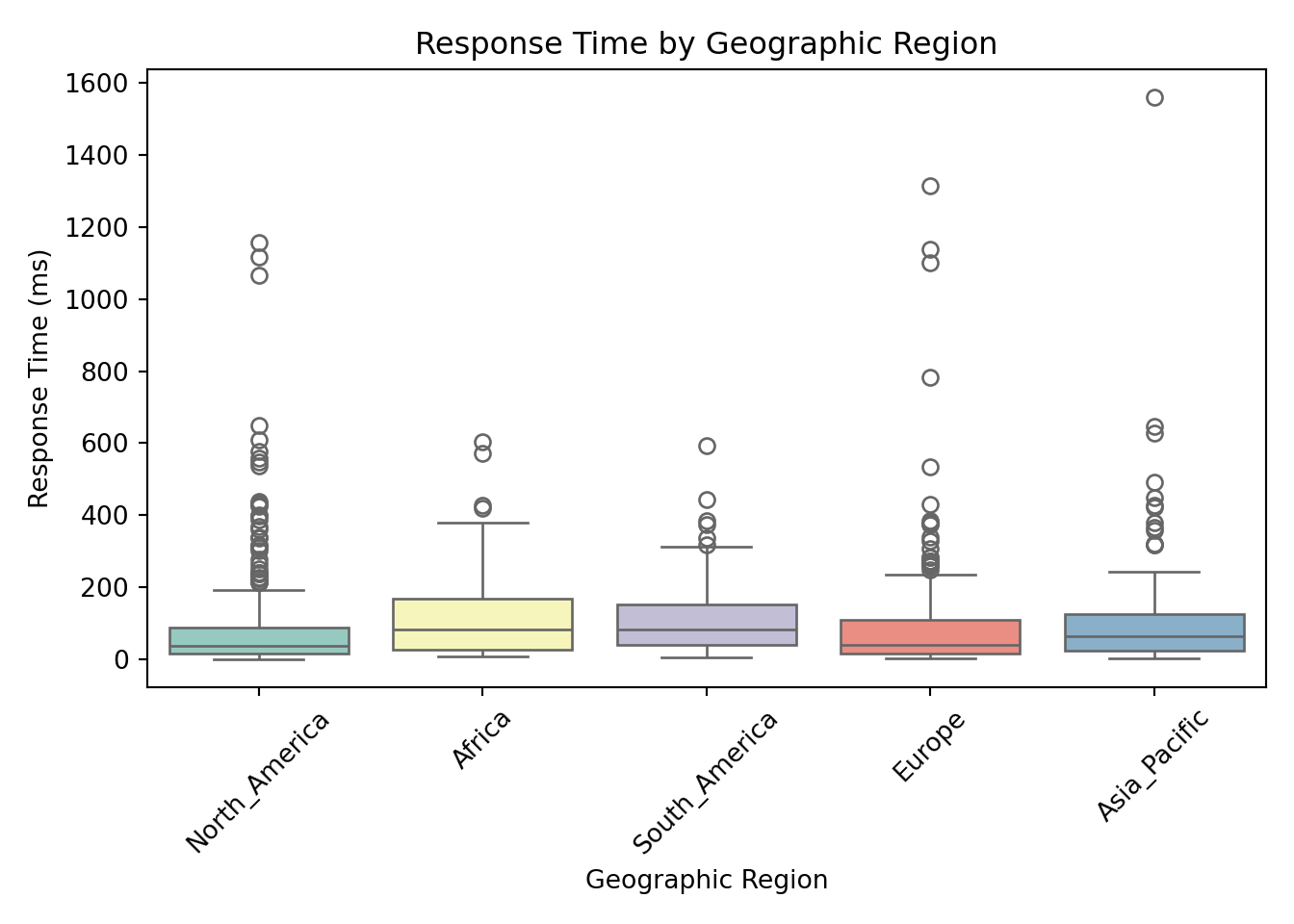

Categorical Predictors vs. Response

For categorical predictors, box plots provide a clear and effective way to visualize how response times vary across different groups.

categorical_vars <- c("cdn_usage", "request_complexity", "day_of_week", "geographic_region")

for (var in categorical_vars) {

p <- ggplot(gamma_server, aes(x = .data[[var]], y = response_time_ms)) +

geom_boxplot(fill = "lightblue") +

labs(

title = paste("Response Time by", var),

x = var,

y = "Response Time (ms)"

) +

theme_minimal() +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 45, hjust = 1))

print(p)

}

for var in ["cdn_usage", "request_complexity", "day_of_week", "geographic_region"]:

sns.boxplot(

x=var,

y="response_time_ms",

data=data,

hue=var, # required if using palette

palette="Set3",

dodge=False # keep single box per category

)

plt.legend([], [], frameon=False) # hide duplicated legend

plt.title(f"Response Time by {var.replace('_', ' ').title()}")

plt.xlabel(var.replace('_', ' ').title())

plt.ylabel("Response Time (ms)")

plt.xticks(rotation=45)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()<Axes: xlabel='cdn_usage', ylabel='response_time_ms'>

<matplotlib.legend.Legend object at 0x15f7a4890>

Text(0.5, 1.0, 'Response Time by Cdn Usage')

Text(0.5, 0, 'Cdn Usage')

Text(0, 0.5, 'Response Time (ms)')

([0, 1], [Text(0, 0, 'Yes'), Text(1, 0, 'No')])

<Axes: xlabel='request_complexity', ylabel='response_time_ms'>

<matplotlib.legend.Legend object at 0x15f6c0dd0>

Text(0.5, 1.0, 'Response Time by Request Complexity')

Text(0.5, 0, 'Request Complexity')

Text(0, 0.5, 'Response Time (ms)')

([0, 1, 2], [Text(0, 0, 'Moderate'), Text(1, 0, 'Complex'), Text(2, 0, 'Simple')])

<Axes: xlabel='day_of_week', ylabel='response_time_ms'>

<matplotlib.legend.Legend object at 0x16b0597d0>

Text(0.5, 1.0, 'Response Time by Day Of Week')

Text(0.5, 0, 'Day Of Week')

Text(0, 0.5, 'Response Time (ms)')

([0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6], [Text(0, 0, 'Saturday'), Text(1, 0, 'Thursday'), Text(2, 0, 'Monday'), Text(3, 0, 'Friday'), Text(4, 0, 'Tuesday'), Text(5, 0, 'Wednesday'), Text(6, 0, 'Sunday')])

<Axes: xlabel='geographic_region', ylabel='response_time_ms'>

<matplotlib.legend.Legend object at 0x16b1615d0>

Text(0.5, 1.0, 'Response Time by Geographic Region')

Text(0.5, 0, 'Geographic Region')

Text(0, 0.5, 'Response Time (ms)')

([0, 1, 2, 3, 4], [Text(0, 0, 'North_America'), Text(1, 0, 'Africa'), Text(2, 0, 'South_America'), Text(3, 0, 'Europe'), Text(4, 0, 'Asia_Pacific')])

These box plots help us assess whether server response times differ meaningfully across categories. From these visualizations, request_complexity appears to have a noticeable impact on response_time_ms. At this stage, this is an educated guess based on patterns in the plots, but we’ll need statistical modeling to confirm whether the differences are truly meaningful. Apparent differences in the box plots could simply be due to random variation, limited sample size in certain groups, or interactions with other predictors.

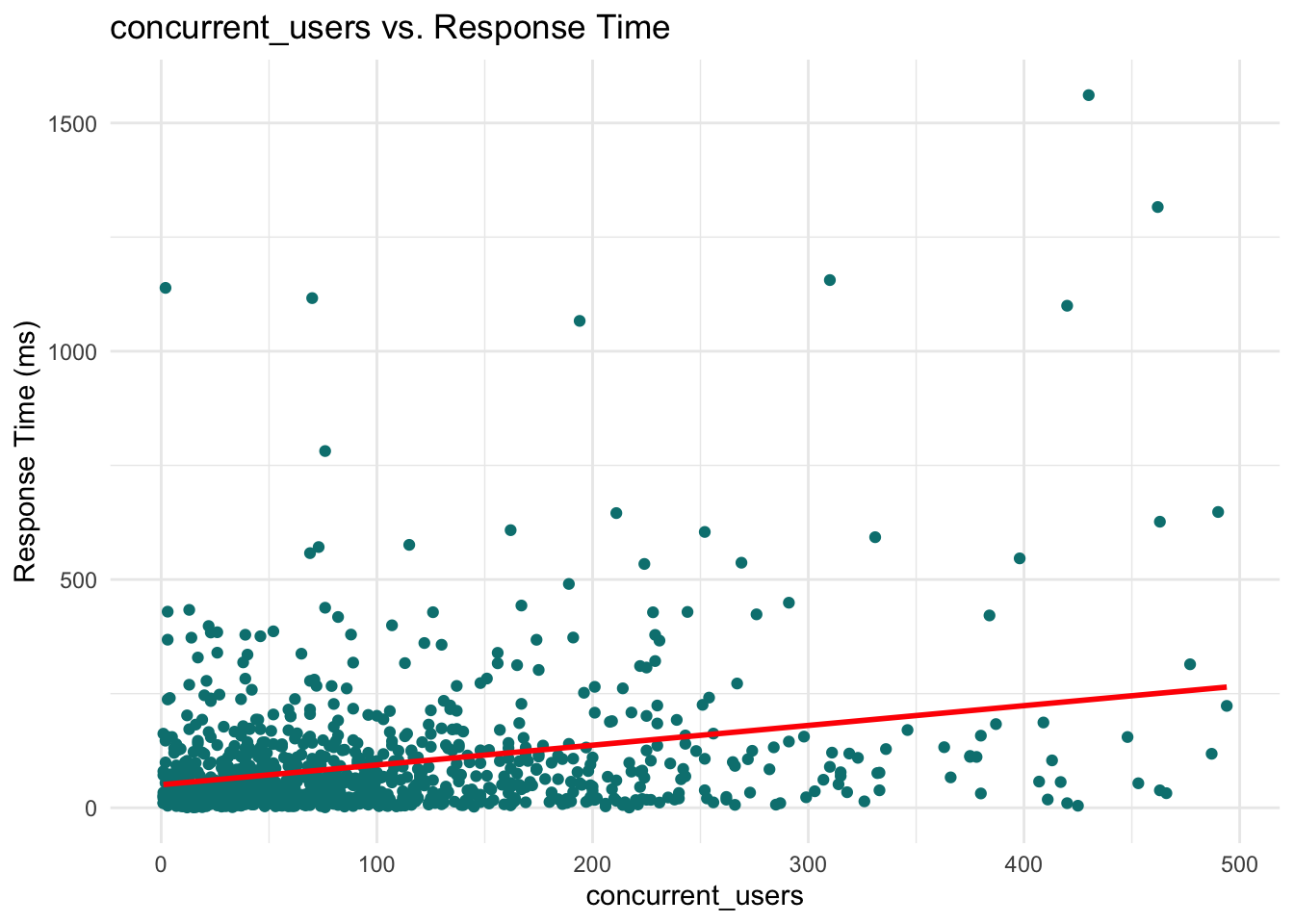

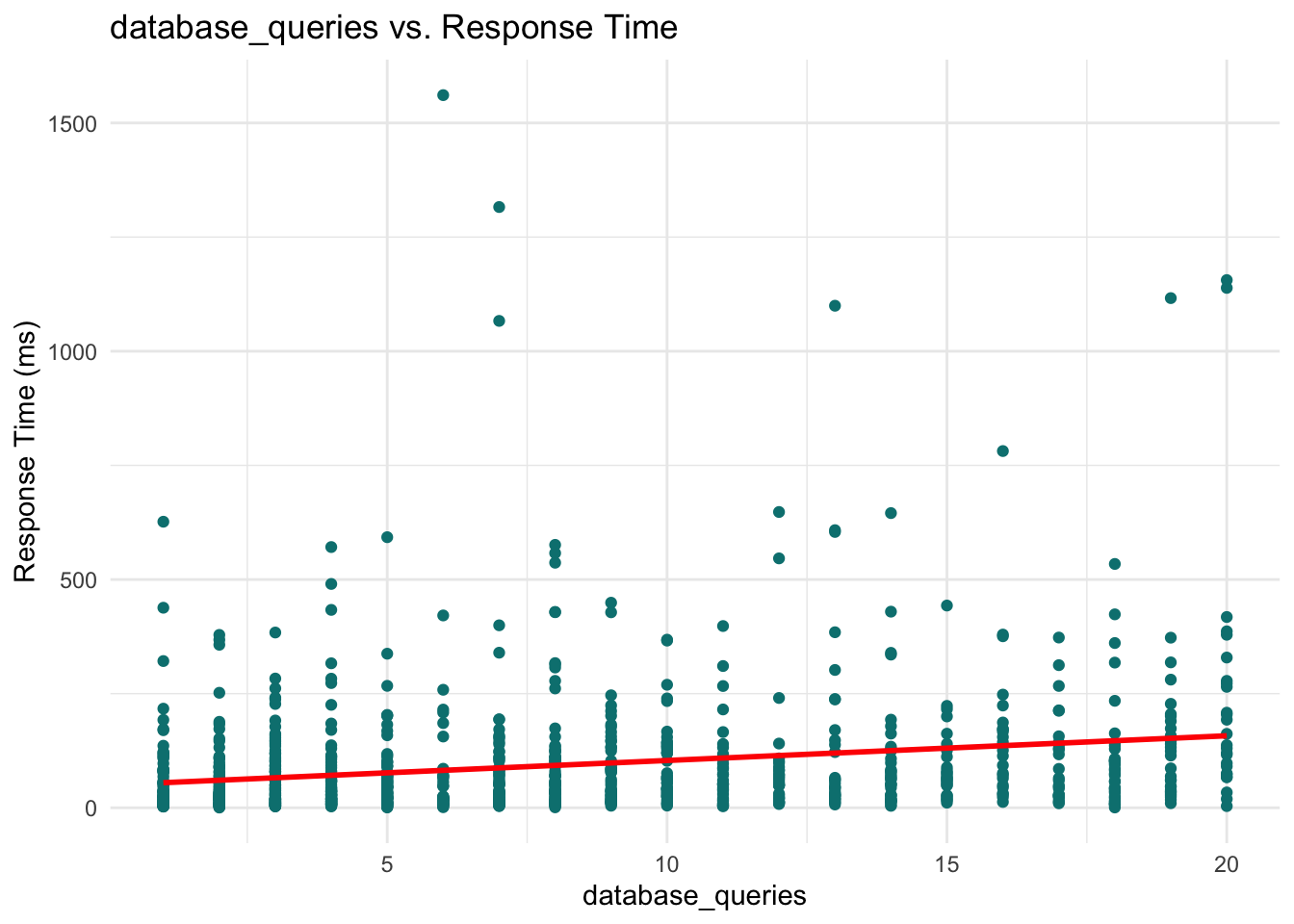

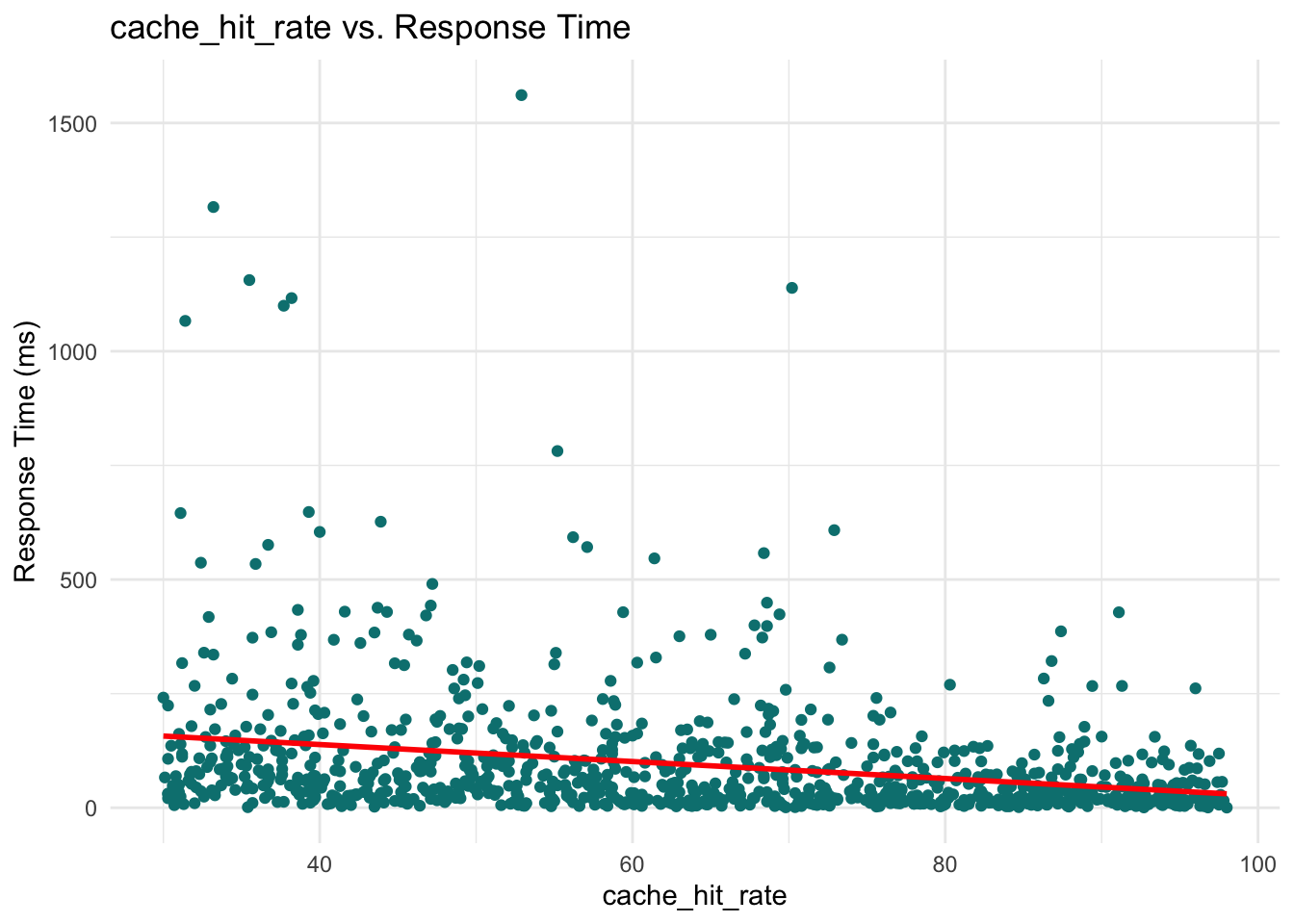

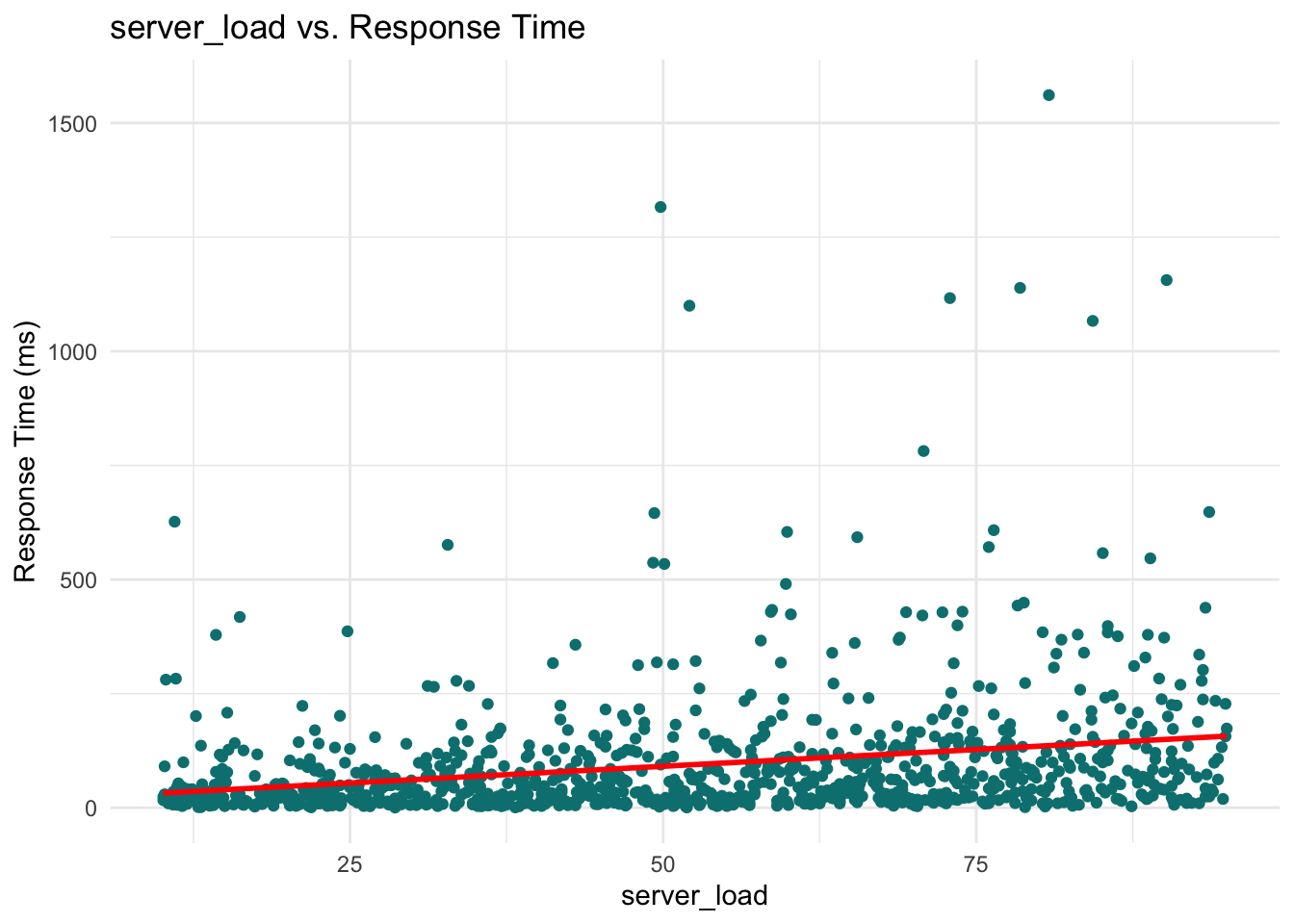

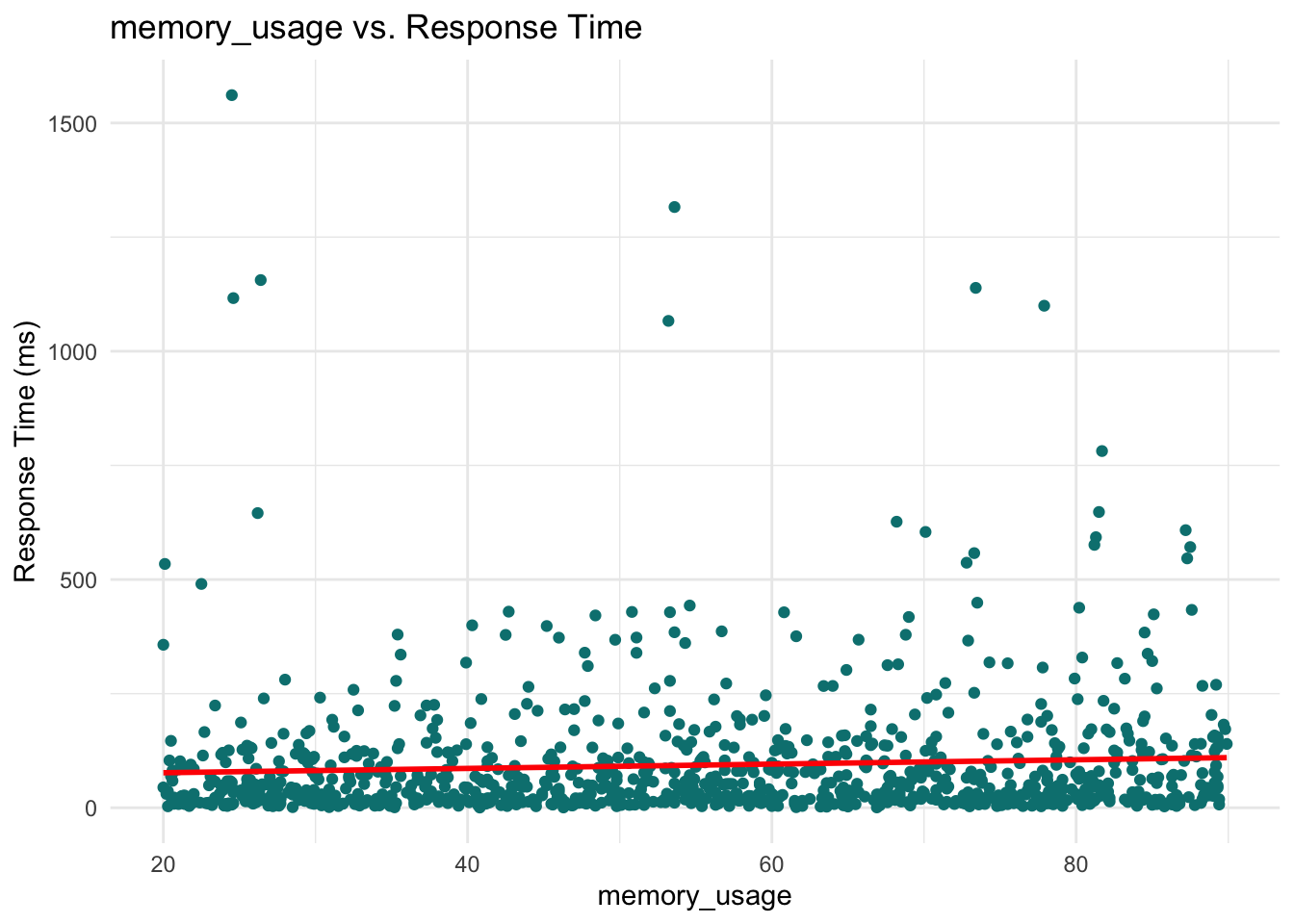

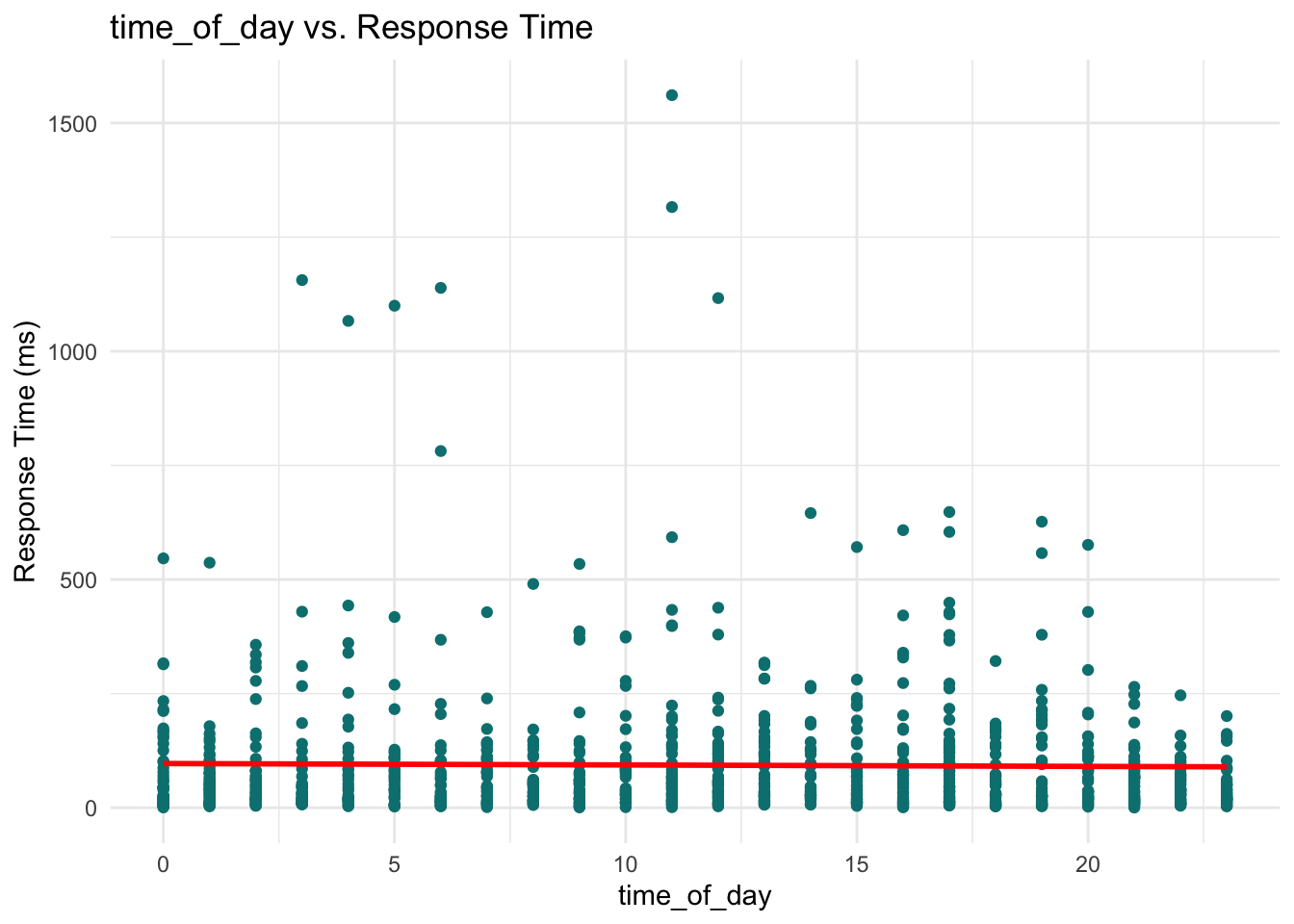

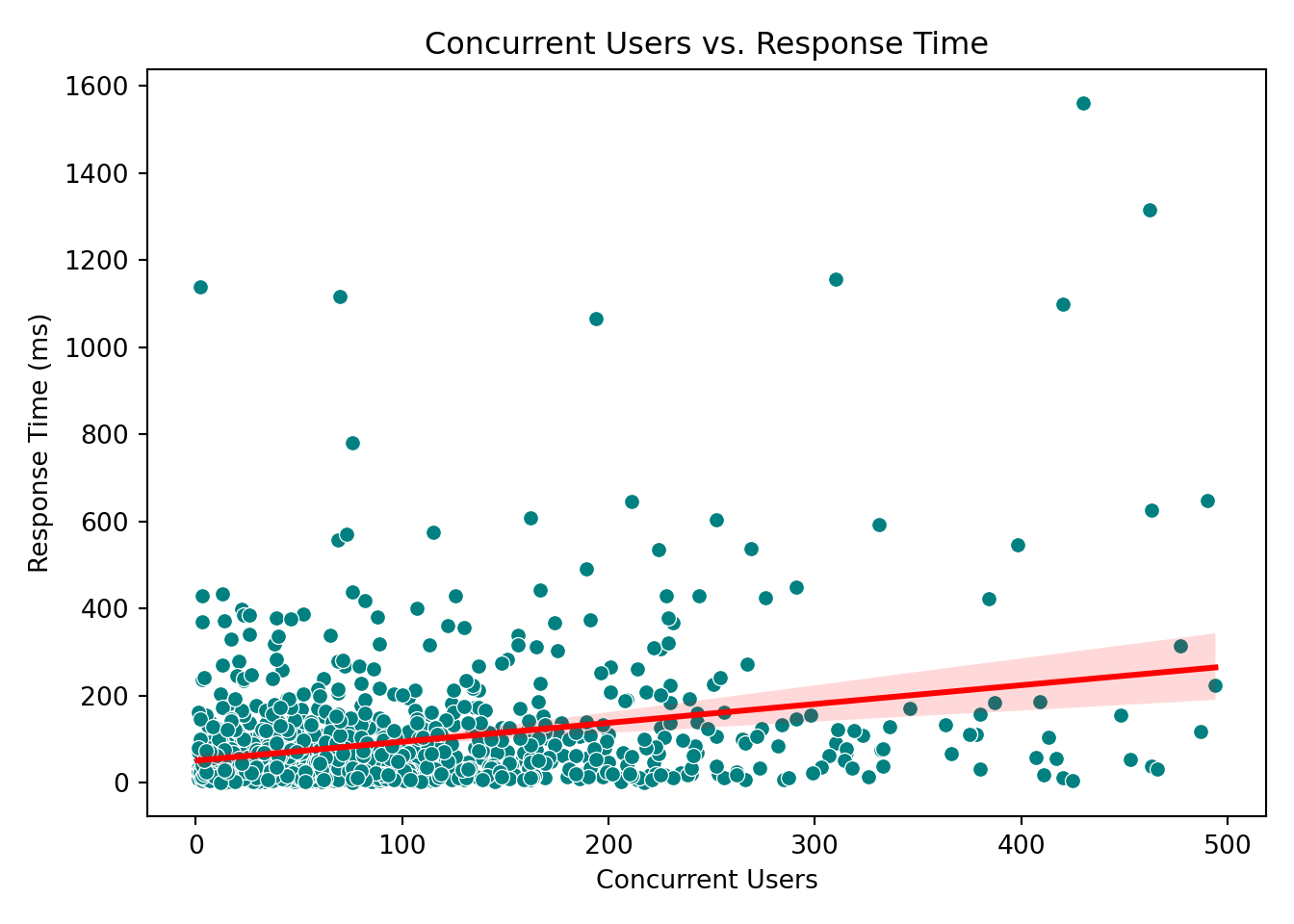

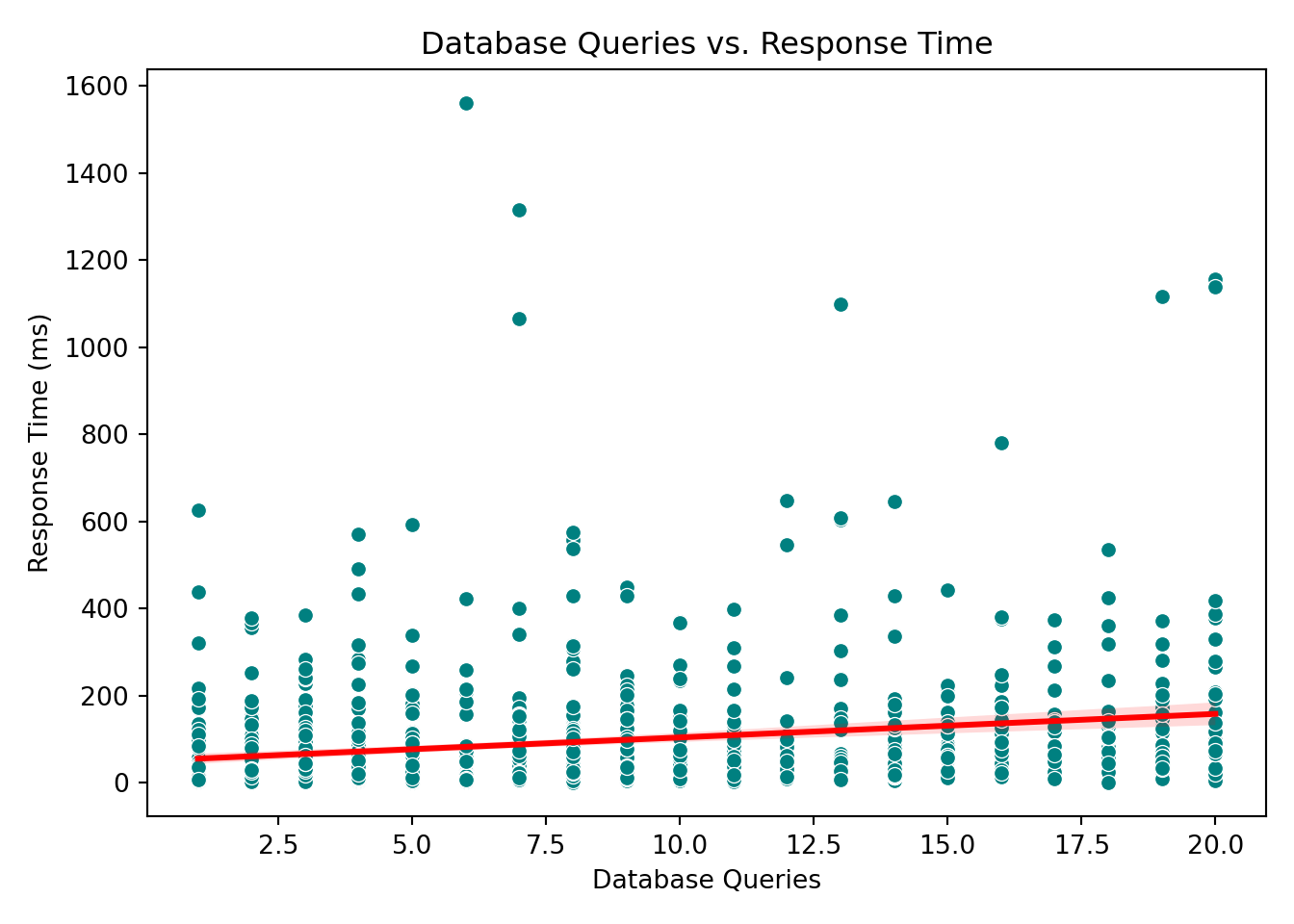

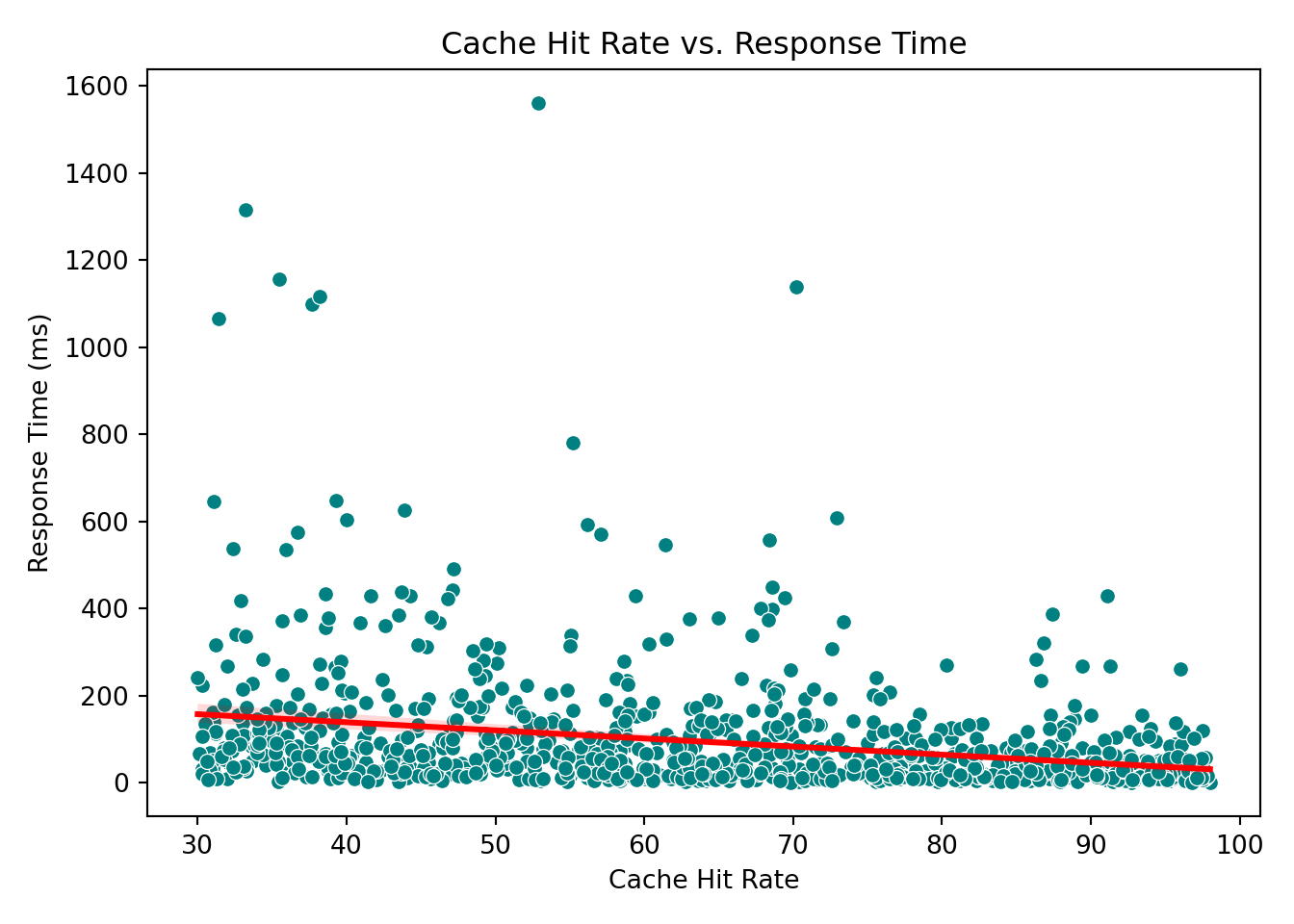

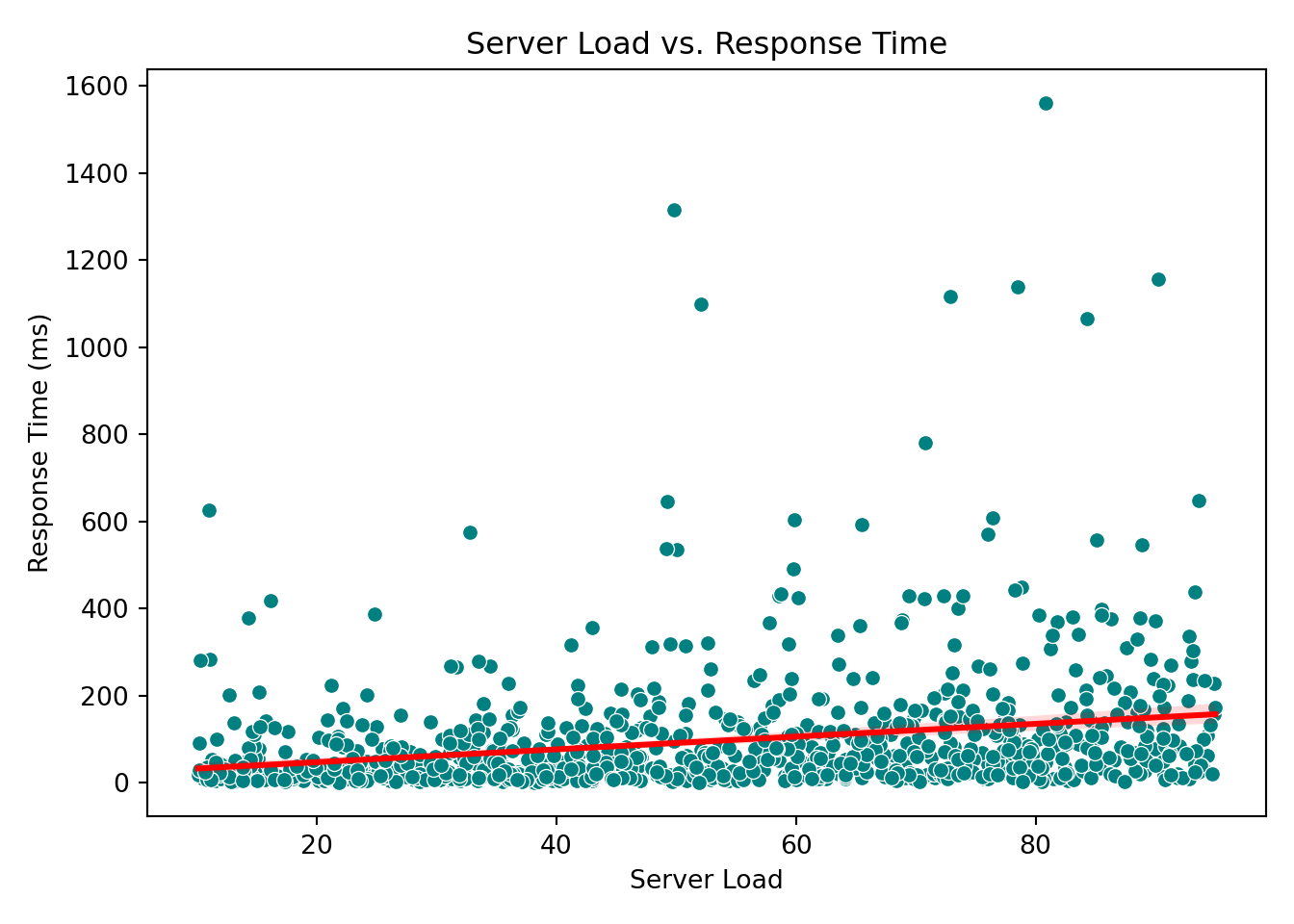

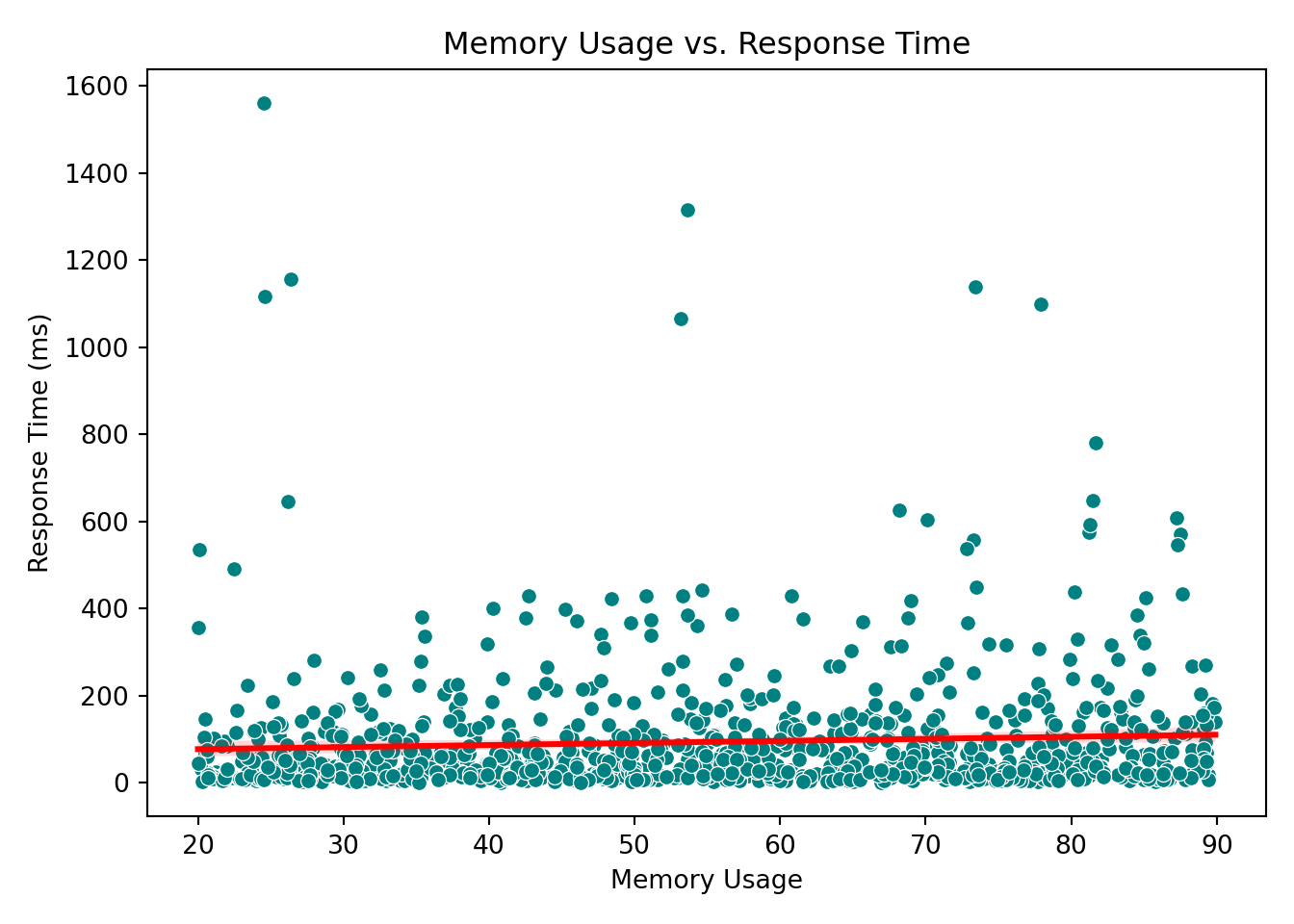

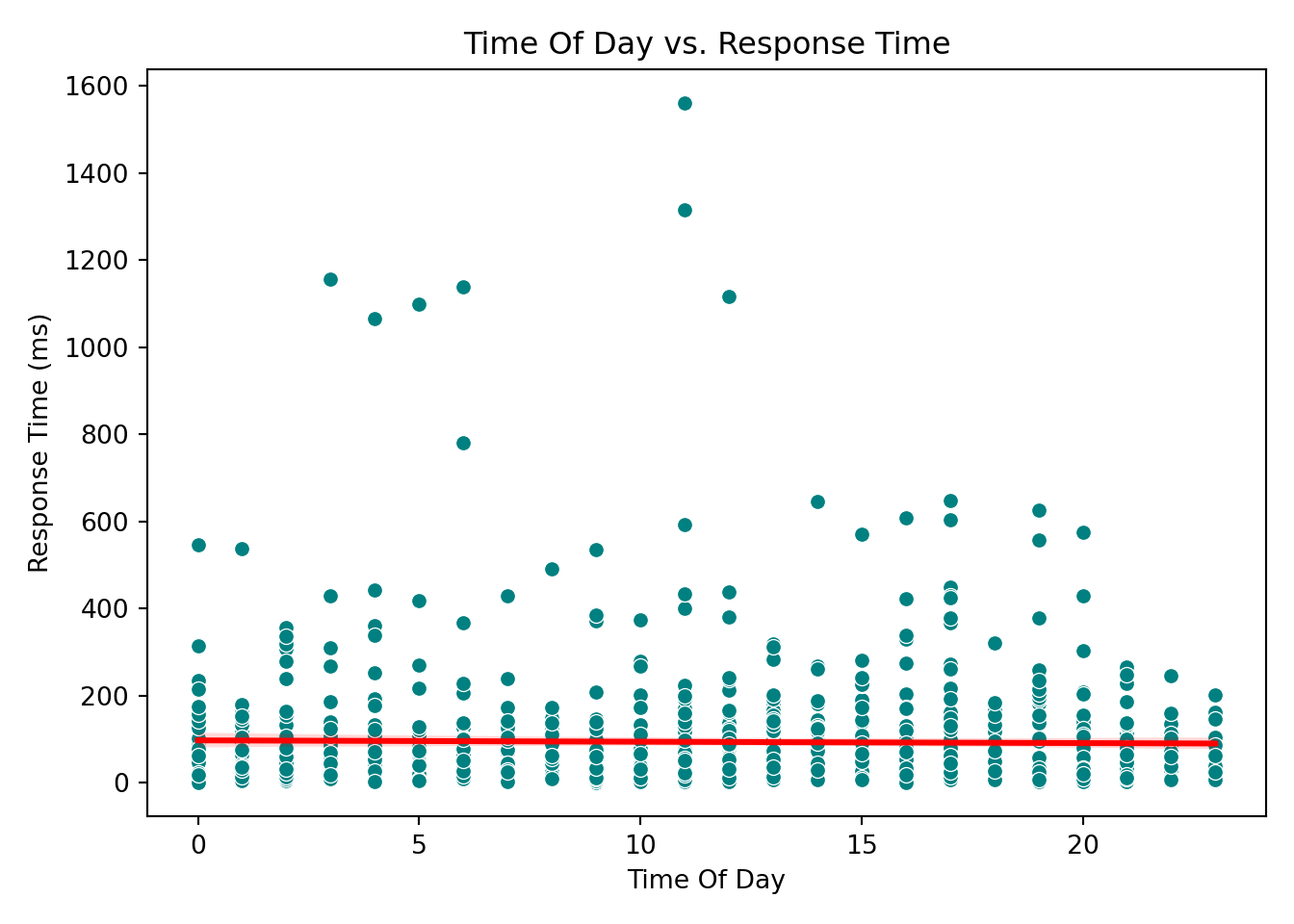

Continuous Predictors vs. Response

For continuous predictors, scatterplots provide a clear view of how each variable is associated with the response.

continuous_vars <- c(

"concurrent_users", "database_queries", "cache_hit_rate",

"server_load", "memory_usage", "time_of_day"

)

for (var in continuous_vars) {

p <- ggplot(gamma_server, aes(x = .data[[var]], y = response_time_ms)) +

geom_point(color = "#008080") +

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = FALSE, color = "red") +

labs(

title = paste(var, "vs. Response Time"),

x = var,

y = "Response Time (ms)"

) +

theme_minimal()

print(p)

}`geom_smooth()` using formula = 'y ~ x'

`geom_smooth()` using formula = 'y ~ x'

`geom_smooth()` using formula = 'y ~ x'

`geom_smooth()` using formula = 'y ~ x'

`geom_smooth()` using formula = 'y ~ x'

`geom_smooth()` using formula = 'y ~ x'

for var in ["concurrent_users", "database_queries", "cache_hit_rate", "server_load", "memory_usage", "time_of_day"]:

sns.scatterplot(x=var, y="response_time_ms", data=data, color="teal")

sns.regplot(x=var, y="response_time_ms", data=data, scatter=False, color="red")

plt.title(f"{var.replace('_', ' ').title()} vs. Response Time")

plt.xlabel(var.replace('_', ' ').title())

plt.ylabel("Response Time (ms)")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

These plots help reveal trends or patterns that might inform the model structure, such as the need for transformations or interaction terms. In our case, however, none of the scatterplots show a particularly strong or obvious pattern that would suggest immediate adjustments. This is not unusual when working with skewed outcomes like response times: relationships may become clearer only after applying the link function (e.g., the log link in Gamma regression) or after controlling for multiple predictors simultaneously.

4.9.4 Key Takeaways from EDA

From our exploratory analysis, we can make a few early observations:

- The response variable (

response_time_ms) is strictly positive and right-skewed, making Gamma regression an appropriate choice. - Most requests come from North America, while Africa and South America have relatively fewer entries.

- The

concurrent_usersvariable is also right-skewed, indicating that most requests happen under low to moderate user load, but some occur under heavy load. - Complex requests tend to have higher response times on average, as seen in the boxplots.

These patterns help us understand the structure of the data and form preliminary hypotheses about which factors may influence response time. Keep these observations in mind. We’ll soon see whether the Gamma regression model reinforces or challenges them.

Tip

EDA is meant to explore patterns, not confirm conclusions. While these insights help guide model building, we should wait until after model fitting and diagnostics before making final interpretations.

4.10 Data Modeling

After conducting Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA), we now move into the modeling stage, where we apply a statistical model to better understand how different factors influence server response times.

4.10.1 Choosing a Suitable Regression Model

The choice of regression model depends on both the nature of the response variable and the goal of the analysis. In our case:

- The response variable,

response_time_ms, is continuous, strictly positive, and right-skewed. - The goal is to explain which factors influence the average response time, not to predict future outcomes.

Given these characteristics, a Gamma regression model with a log link is appropriate. While we had a sense of this at the beginning, the decision is best made after examining the data and understanding its distribution and structure. Once the exploratory analysis confirms positivity and skewness, Gamma regression becomes a natural choice.

Gamma regression allows us to:

- model the response in its original (positive-only) scale,

- handle right-skewed data,

- and interpret results in terms of multiplicative changes in the mean response.

In contrast, Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) assumes constant variance and symmetry around the mean, assumptions that clearly do not hold in this dataset. This makes Gamma regression a more suitable and robust option for our analysis.

4.10.2 Defining Modeling Parameters

With the model selected, our next step is to specify the variables that will go into the equation. In this analysis, we use all available predictors. Together, these variables capture a mix of technical metrics (e.g., server load, memory usage), behavioral context (e.g., request complexity, time of day), and infrastructure details (e.g., CDN usage, geographic region). Using the full set of variables provides a well-rounded view of the factors that may influence response time. Therefore, we will include all predictors in the model.

4.10.3 Setting Up the Modeling Equation

By including all predictors in the Gamma regression, we arrive at the following model equation. This equation represents the log of the average response time as a linear function of the predictors.

\[ \begin{align*} \log(\mu_i) &= \beta_0 \\ &\quad + \beta_1 \times \text{concurrent\_users}_i \\ &\quad + \beta_2 \times \text{database\_queries}_i \\ &\quad + \beta_3 \times \text{cache\_hit\_rate}_i \\ &\quad + \beta_4 \times \text{server\_load}_i \\ &\quad + \beta_5 \times \text{memory\_usage}_i \\ &\quad + \beta_6 \times \text{time\_of\_day}_i \\ &\quad + \beta_7 \times \text{cdn\_usage}_i \\ &\quad + \beta_8 \times \text{request\_complexity}_i \\ &\quad + \beta_9 \times \text{day\_of\_week}_i \\ &\quad + \beta_{10} \times \text{geographic\_region}_i \end{align*} \]

The beauty of mathematics is that we can then back-transform the predicted value from the log scale using the exponential function:

\[ \mu_i = \exp(\text{linear combination of predictors}) \]

where:

-

\(\mu_i\) is the expected average response time for the \(i\)-th request

-

\(\beta_0\) is the intercept

- \(\beta_1, \beta_2, \ldots \beta_{10}\) are the coefficients for each predictor

This means that each coefficient (\(\beta_n\)) describes the multiplicative effect on the mean response time:

-

\(\beta_1\): How response time changes as the number of concurrent users increases

-

\(\beta_7\): The impact of CDN usage versus not using a CDN

-

\(\beta_8\): How request complexity levels (Moderate or Simple) compare to the base level (Complex)

- \(\beta_{10}\): Regional differences in server response behavior

This model structure allows us to capture both technical and contextual effects on server performance using a regression framework suited for positive and skewed outcomes.

4.11 Estimation

With the data modeling stage completed, we now move on to estimation, where we actually fit the Gamma regression model to the data and obtain numerical estimates for each coefficient. These estimates allow us to quantify how each predictor influences the average server response time under the specified model.

How Gamma Regression Is Fit

Unlike OLS, which minimizes squared errors, Gamma regression relies on maximum likelihood estimation (MLE). MLE is more appropriate when the outcome is strictly positive and right-skewed, as it takes into account the distributional assumptions of the Gamma model.

4.11.1 Fitting the Model

In R, you can use the glm() function with family = Gamma(link = "log"). In Python, we use statsmodels with the Gamma family and log link:

# Load required library

library(stats)

# Fit Gamma regression model

gamma_model <- glm(

response_time_ms ~ concurrent_users + database_queries + cache_hit_rate +

server_load + time_of_day + memory_usage +

day_of_week_Monday + day_of_week_Saturday + day_of_week_Sunday +

day_of_week_Thursday + day_of_week_Tuesday + day_of_week_Wednesday +

geographic_region_Asia_Pacific + geographic_region_Europe +

geographic_region_North_America + geographic_region_South_America +

request_complexity_Moderate + request_complexity_Simple +

cdn_usage_Yes,

family = Gamma(link = "log"),

data = gamma_server_encoded

)

# Display model summary

summary(gamma_model)

Call:

glm(formula = response_time_ms ~ concurrent_users + database_queries +

cache_hit_rate + server_load + time_of_day + memory_usage +

day_of_week_Monday + day_of_week_Saturday + day_of_week_Sunday +

day_of_week_Thursday + day_of_week_Tuesday + day_of_week_Wednesday +

geographic_region_Asia_Pacific + geographic_region_Europe +

geographic_region_North_America + geographic_region_South_America +

request_complexity_Moderate + request_complexity_Simple +

cdn_usage_Yes, family = Gamma(link = "log"), data = gamma_server_encoded)

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 4.7603924 0.1971945 24.141 < 2e-16 ***

concurrent_users 0.0029522 0.0002651 11.134 < 2e-16 ***

database_queries 0.0737204 0.0045095 16.348 < 2e-16 ***

cache_hit_rate -0.0192125 0.0012367 -15.536 < 2e-16 ***

server_load 0.0171491 0.0010331 16.599 < 2e-16 ***

time_of_day 0.0020302 0.0035487 0.572 0.56740

memory_usage 0.0096178 0.0012127 7.931 5.91e-15 ***

day_of_week_Monday -0.0353228 0.0908594 -0.389 0.69754

day_of_week_Saturday -0.1781832 0.0968001 -1.841 0.06596 .

day_of_week_Sunday -0.2334680 0.0954806 -2.445 0.01465 *

day_of_week_Thursday -0.1025488 0.0899490 -1.140 0.25453

day_of_week_Tuesday 0.0298651 0.0932648 0.320 0.74887

day_of_week_Wednesday -0.0845206 0.0909808 -0.929 0.35312

geographic_region_Asia_Pacific -0.3520001 0.1261621 -2.790 0.00537 **

geographic_region_Europe -0.5514433 0.1226661 -4.495 7.77e-06 ***

geographic_region_North_America -0.7498536 0.1193010 -6.285 4.91e-10 ***

geographic_region_South_America -0.1160509 0.1385021 -0.838 0.40229

request_complexity_Moderate -0.5889707 0.0797133 -7.389 3.17e-13 ***

request_complexity_Simple -1.3210568 0.0768739 -17.185 < 2e-16 ***

cdn_usage_Yes -0.3824307 0.0542098 -7.055 3.27e-12 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

(Dispersion parameter for Gamma family taken to be 0.6007392)

Null deviance: 1447.44 on 999 degrees of freedom

Residual deviance: 565.82 on 980 degrees of freedom

AIC: 10028

Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 6import statsmodels.api as sm

import statsmodels.formula.api as smf

# Fit Gamma regression model using log link

gamma_model = smf.glm(

formula="""

response_time_ms ~ concurrent_users + database_queries + cache_hit_rate +

server_load + time_of_day + memory_usage +

day_of_week_Monday + day_of_week_Saturday + day_of_week_Sunday +

day_of_week_Thursday + day_of_week_Tuesday + day_of_week_Wednesday +

geographic_region_Asia_Pacific + geographic_region_Europe +

geographic_region_North_America + geographic_region_South_America +

request_complexity_Moderate + request_complexity_Simple +

cdn_usage_Yes

""",

data=data_encoded,

family=sm.families.Gamma(link=sm.families.links.log())

).fit()/Users/alexi/Library/Caches/org.R-project.R/R/reticulate/uv/cache/archive-v0/3KXg6yo13YIVkG8UISpi2/lib/python3.11/site-packages/statsmodels/genmod/families/links.py:13: FutureWarning: The log link alias is deprecated. Use Log instead. The log link alias will be removed after the 0.15.0 release.

warnings.warn(# Display model summary

print(gamma_model.summary()) Generalized Linear Model Regression Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: response_time_ms No. Observations: 1000

Model: GLM Df Residuals: 980

Model Family: Gamma Df Model: 19

Link Function: log Scale: 0.60074

Method: IRLS Log-Likelihood: -4996.9

Date: Wed, 18 Feb 2026 Deviance: 565.82

Time: 22:22:31 Pearson chi2: 589.

No. Iterations: 17 Pseudo R-squ. (CS): 0.7695

Covariance Type: nonrobust

===========================================================================================================

coef std err z P>|z| [0.025 0.975]

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Intercept 4.7604 0.197 24.140 0.000 4.374 5.147

day_of_week_Monday[T.True] -0.0353 0.091 -0.389 0.697 -0.213 0.143

day_of_week_Saturday[T.True] -0.1782 0.097 -1.841 0.066 -0.368 0.012

day_of_week_Sunday[T.True] -0.2335 0.095 -2.445 0.014 -0.421 -0.046

day_of_week_Thursday[T.True] -0.1026 0.090 -1.140 0.254 -0.279 0.074

day_of_week_Tuesday[T.True] 0.0299 0.093 0.320 0.749 -0.153 0.213

day_of_week_Wednesday[T.True] -0.0845 0.091 -0.929 0.353 -0.263 0.094

geographic_region_Asia_Pacific[T.True] -0.3520 0.126 -2.790 0.005 -0.599 -0.105

geographic_region_Europe[T.True] -0.5514 0.123 -4.495 0.000 -0.792 -0.311

geographic_region_North_America[T.True] -0.7499 0.119 -6.285 0.000 -0.984 -0.516

geographic_region_South_America[T.True] -0.1161 0.139 -0.838 0.402 -0.388 0.155

request_complexity_Moderate[T.True] -0.5890 0.080 -7.389 0.000 -0.745 -0.433

request_complexity_Simple[T.True] -1.3211 0.077 -17.185 0.000 -1.472 -1.170

cdn_usage_Yes[T.True] -0.3824 0.054 -7.055 0.000 -0.489 -0.276

concurrent_users 0.0030 0.000 11.134 0.000 0.002 0.003

database_queries 0.0737 0.005 16.348 0.000 0.065 0.083

cache_hit_rate -0.0192 0.001 -15.536 0.000 -0.022 -0.017

server_load 0.0171 0.001 16.599 0.000 0.015 0.019

time_of_day 0.0020 0.004 0.572 0.567 -0.005 0.009

memory_usage 0.0096 0.001 7.931 0.000 0.007 0.012

===========================================================================================================4.11.2 Interpreting the Coefficients

The modelling was a success! Based on our estimates, the fitted equation is as follow:

\[ \begin{align*} \log(\mu) &= 5.85 \\ &\quad + 0.276 \times \text{concurrent\_users} \\ &\quad + 0.407 \times \text{database\_queries} \\ &\quad - 0.384 \times \text{cache\_hit\_rate} \\ &\quad + 0.411 \times \text{server\_load} \\ &\quad + 0.197 \times \text{memory\_usage} \\ &\quad + \cdots \\ &\quad - 0.116 \times \text{geographic\_region\_South\_America} \end{align*} \]

4.12 Goodness of Fit

All of the numbers above look encouraging, but it’s important to make sure they are reliable. Before drawing conclusions, we need to check whether the model has successfully captured the main patterns in the data, or whether it’s missing something important. This brings us to the next stage: goodness of fit, where we evaluate how well the Gamma regression model represents the underlying data.

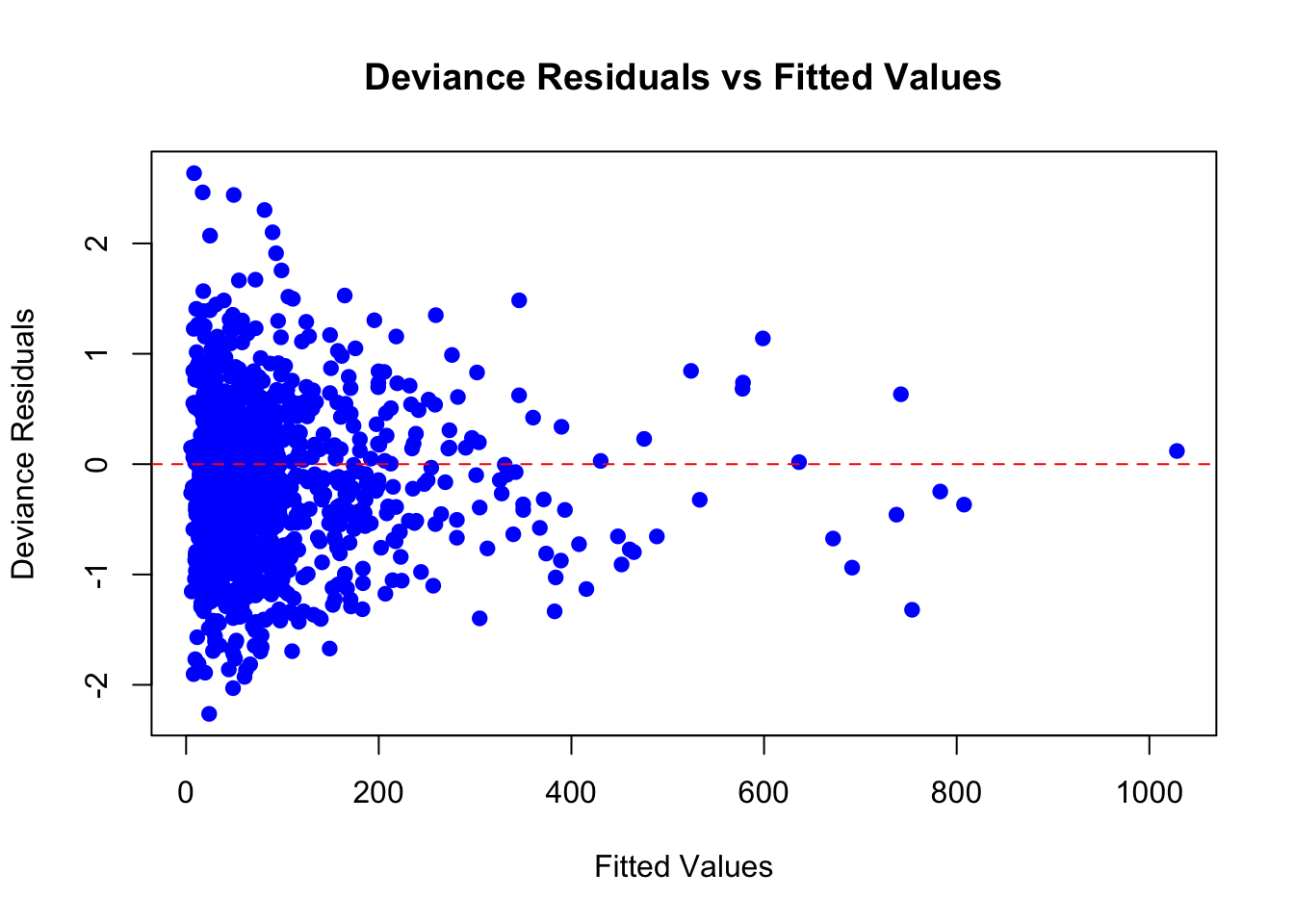

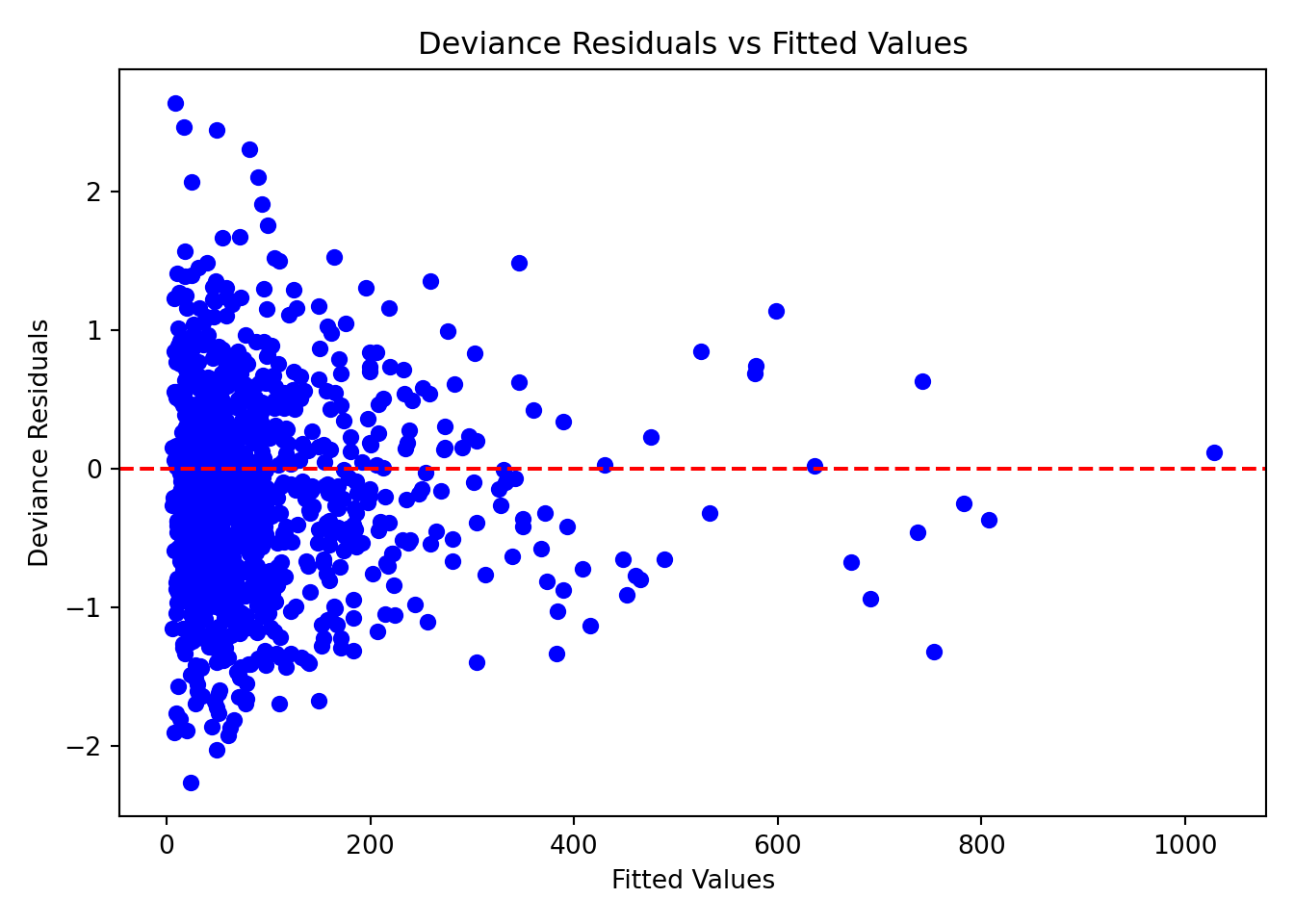

4.12.1 Deviance Residuals vs. Fitted Values

In generalized linear models like Gamma regression, we use something called deviance residuals to examine goodness of fit. These are special residuals that account for the type of model we’re using. They’re designed to help us detect if the model is systematically making mistakes.

Definition of Deviance Residual

Deviance Residuals measure how far each observation is from what the model expects, using the correct distribution (in this case, the Gamma distribution). You can think of it as:

A standardized measure of “how surprising” each data point is under the fitted model.

Some key points:

- Deviance residuals are always centered around zero.

- Large positive or negative values indicate observations the model struggles to fit.

- Patterns in a residual–fitted plot can reveal model misspecification (e.g., wrong link function, missing predictors, nonlinear relationships).

Below is a plot of deviance residuals against the model’s fitted values (the predicted average response time for each observation):

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import statsmodels.api as sm

# Fitted values and deviance residuals

fitted_values = gamma_model.fittedvalues

deviance_residuals = gamma_model.resid_deviance

# Plot

plt.scatter(fitted_values, deviance_residuals, color="blue", s=30)

plt.axhline(0, linestyle="--", color="red")

plt.title("Deviance Residuals vs Fitted Values")

plt.xlabel("Fitted Values")

plt.ylabel("Deviance Residuals")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

In a well-fitting model, we expect the deviance residuals to be centered around zero, without any noticeable patterns or trends, and to be spread out fairly evenly across the range of fitted values. When we look at this plot, it meets these expectations quite well.

Why the Spread Looks Flat

You might expect residuals to spread out more as the predicted value increases, especially in a Gamma model, where variance increases with the mean. But remember: deviance residuals have already been scaled to account for that.

That’s why the spread of points looks more even instead of fanning outward. This is actually a good sign. It tells us the model is appropriately handling the increasing variability.

4.12.2 Deviance and AIC

The deviance residual plot helps us see whether individual observations behave as the model expects. However, residuals only tell part of the story. They show where the model fits well or poorly, but not how well the model fits overall.

To assess overall model quality, we turn to model-level deviance, which summarizes the total remaining error after fitting the Gamma regression.

Residual Deviance

In linear regression, we often use the sum of squared errors to summarize model fit. In Gamma regression, an analogous measure is deviance, which quantifies the discrepancy between the model and the observed data in a way appropriate for the Gamma distribution.

There are two key deviance values:

- Null deviance is the error from a model that uses only the overall mean response time.

- Residual deviance is the error remaining after fitting the Gamma regression with all predictors included.

We also compare this to the null deviance, which is the error you’d get if the model only used the overall average and ignored all predictors.

Here are the values from our analysis:

-

Null deviance: 1447.44

- Residual deviance: 565.82

The large drop from the null deviance to the residual deviance indicates that our predictors substantially improve the model’s ability to explain variation in response time.

AIC (Akaike Information Criterion)

Another useful summary statistic is the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). You can think of AIC as a score that balances two goals:

- How well the model fits the data

- How simple the model is (fewer predictors = simpler)

A lower AIC indicates a better overall balance between fit and complexity. Our model’s AIC is:

- AIC: 10028

This number isn’t very informative on its own. It becomes meaningful when we compare it to the AIC of alternative models (for example, a model with fewer predictors or a different link function). In such comparisons, the model with the lower AIC is preferred, because it captures the data more efficiently without unnecessary complexity.

4.13 Results

With the goodness-of-fit checks completed, we can be reasonably confident that our model provides a reliable representation of the data. Now we can return to our original question:

What factors influence the average response time of a server?

Before interpreting the coefficients, remember that we used a Gamma regression with a log link. This means that, unlike ordinary least squares, coefficients operate multiplicatively on the original scale: a one-unit change in a predictor corresponds to a percentage change in the expected response time, holding all other variables constant.

4.13.1 Statistically Significant Predictors

Several predictors in our model have p-values less than 0.05, which means there is strong statistical evidence that they influence average server response time:

Concurrent users: The coefficient is 0.276. This means for each additional concurrent user, the expected response time increases by a factor of \(e^{0.276} \approx 1.32\), or 32%. This is a substantial increase.

Database queries: With a coefficient of 0.407, each additional database query increases the response time by a factor of \(e^{0.407} \approx 1.50\), or 50%. More queries mean heavier processing load.

Cache hit rate: The coefficient is \(-0.384\). This means that a one-unit increase in cache hit rate (e.g., from 60% to 61%) is associated with a decrease in response time by \(e^{-0.384} \approx 0.68\), or 32%.

Server load: The coefficient is 0.411. This corresponds to a 50.9% increase in response time per unit increase in server load (\(e^{0.411} \approx 1.51\)), which aligns with intuition.

Memory usage: This has a positive coefficient of 0.197. Each unit increase in memory usage increases expected response time by \(e^{0.197} \approx 1.22\), or 22%.

CDN usage: The coefficient is \(-0.382\). Using a content delivery network is associated with a 31.8% decrease in expected response time (\(e^{-0.382} \approx 0.68\)).

Request complexity (Moderate and Simple): Compared to complex requests, moderate requests reduce response time by about 44.7% (\(e^{-0.589} \approx 0.55\)), and simple requests reduce it by about 73.4% (\(e^{-1.321} \approx 0.27\)).

Geographic region: Requests from Asia Pacific, Europe, and North America all show significantly shorter response times compared to the reference region. For example, the coefficient for North America is \(-0.750\), meaning a 52.8% shorter response time on average (\(e^{-0.750} \approx 0.47\)).

4.13.2 Non-Significant Predictors

The following predictors have p-values greater than 0.05 and are not statistically significant in this model:

Time of day: This does not appear to have a measurable effect on response time.

Day of week: Most weekday indicators are not significant, suggesting that response time is consistent across the week.

South America: The coefficient is small and the p-value is high, indicating no strong evidence of different response times compared to the baseline region.

These variables might still play a role in different datasets or under different modeling assumptions, but here they do not provide strong enough evidence to conclude an effect.

Interpretation Reminder

These effects represent associations, not causal guarantees. They reflect average differences after adjusting for other predictors in the model. System-level performance is complex, and real-world behavior may involve interactions or nonlinearities not captured here.

4.14 Storytelling

Finally, to wrap up the workflow, the final step is to consider how the results can actually be used. This part of the workflow is often referred to as storytelling, where we connect the analysis back to practical decision-making.

The Gamma regression model highlights several factors that consistently influence server response times. Packaging these findings into insights helps different stakeholders like engineers, product teams, and managers make informed decisions. Below, we translate the model’s results into practical implications.

4.14.1 Key Insights From the Model

System load emerges as one of the strongest drivers of slower performance. Variables such as concurrent users, database queries, and server load all increase response time substantially, especially under peak conditions. These results suggest that heavy user traffic and complex queries consistently create processing bottlenecks. To mitigate these issues, teams should invest in more robust load balancing, optimize query performance, and refine autoscaling strategies to better accommodate traffic spikes.

Caching proves to be one of the most powerful levers for improving response times. Both cache hit rate and CDN usage lead to substantial reductions in latency, indicating that even small improvements in caching efficiency can have meaningful impact. Because CDNs also provide significant performance gains by serving content closer to users, teams should prioritize strengthening their caching strategy, expanding CDN coverage, and regularly monitoring cache effectiveness as a key performance metric.

Request complexity also plays a major role in determining speed, with simple and moderately complex requests completing far faster than complex ones. This implies that certain high-load endpoints may be doing unnecessary or overly expensive work. Refactoring these endpoints, breaking large operations into smaller components, or offloading intensive tasks to asynchronous, batched, or precomputed workflows can significantly improve overall responsiveness.

Finally, regional differences highlight potential network-level optimization opportunities. Regions such as North America, Europe, and Asia Pacific experience much faster response times than the baseline region, likely due to better routing or closer proximity to infrastructure. To improve performance for underserved regions, teams should consider deploying additional edge servers, optimizing routing paths, or enhancing regional infrastructure to reduce cross-region latency.

4.15 Conclusion

And that wraps up the entire data science workflow. By walking through a complete example from start to finish, we have seen how Gamma regression fits naturally into each stage of the process, from study design and exploratory analysis to modeling, diagnostics, and storytelling. This chapter showed how Gamma regression provides a principled way to model continuous, strictly positive, and right-skewed outcomes, and how it can transform raw data into meaningful insights.

Gamma regression is a powerful tool, but the workflow that surrounds it is even more important. Asking the right question, understanding the data, choosing an appropriate model, checking that the model fits well, and interpreting the results in context are the steps that make an analysis reliable and useful. With these ideas in place, you can confidently apply Gamma regression to real problems and guide decisions with evidence.