mindmap

root((Regression

Analysis)

Continuous <br/>Outcome Y

{{Unbounded <br/>Outcome Y}}

)Chapter 3: <br/>Ordinary <br/>Least Squares <br/>Regression(

(Normal <br/>Outcome Y)

{{Nonnegative <br/>Outcome Y}}

)Chapter 4: <br/>Gamma Regression(

(Gamma <br/>Outcome Y)

{{Bounded <br/>Outcome Y <br/> between 0 and 1}}

)Chapter 5: Beta <br/>Regression(

(Beta <br/>Outcome Y)

{{Nonnegative <br/>Survival <br/>Time Y}}

)Chapter 6: <br/>Parametric <br/> Survival <br/>Regression(

(Exponential <br/>Outcome Y)

(Weibull <br/>Outcome Y)

(Lognormal <br/>Outcome Y)

)Chapter 7: <br/>Semiparametric <br/>Survival <br/>Regression(

(Cox Proportional <br/>Hazards Model)

(Hazard Function <br/>Outcome Y)

Discrete <br/>Outcome Y

{{Binary <br/>Outcome Y}}

{{Ungrouped <br/>Data}}

)Chapter 8: <br/>Binary Logistic <br/>Regression(

(Bernoulli <br/>Outcome Y)

{{Grouped <br/>Data}}

)Chapter 9: <br/>Binomial Logistic <br/>Regression(

(Binomial <br/>Outcome Y)

{{Count <br/>Outcome Y}}

{{Equidispersed <br/>Data}}

)Chapter 10: <br/>Classical Poisson <br/>Regression(

(Poisson <br/>Outcome Y)

10 Classical Poisson Regression

When to Use and Not Use Classical Poisson Regression

Classical Poisson regression is a type of generalized linear model that is appropriately used under the following conditions:

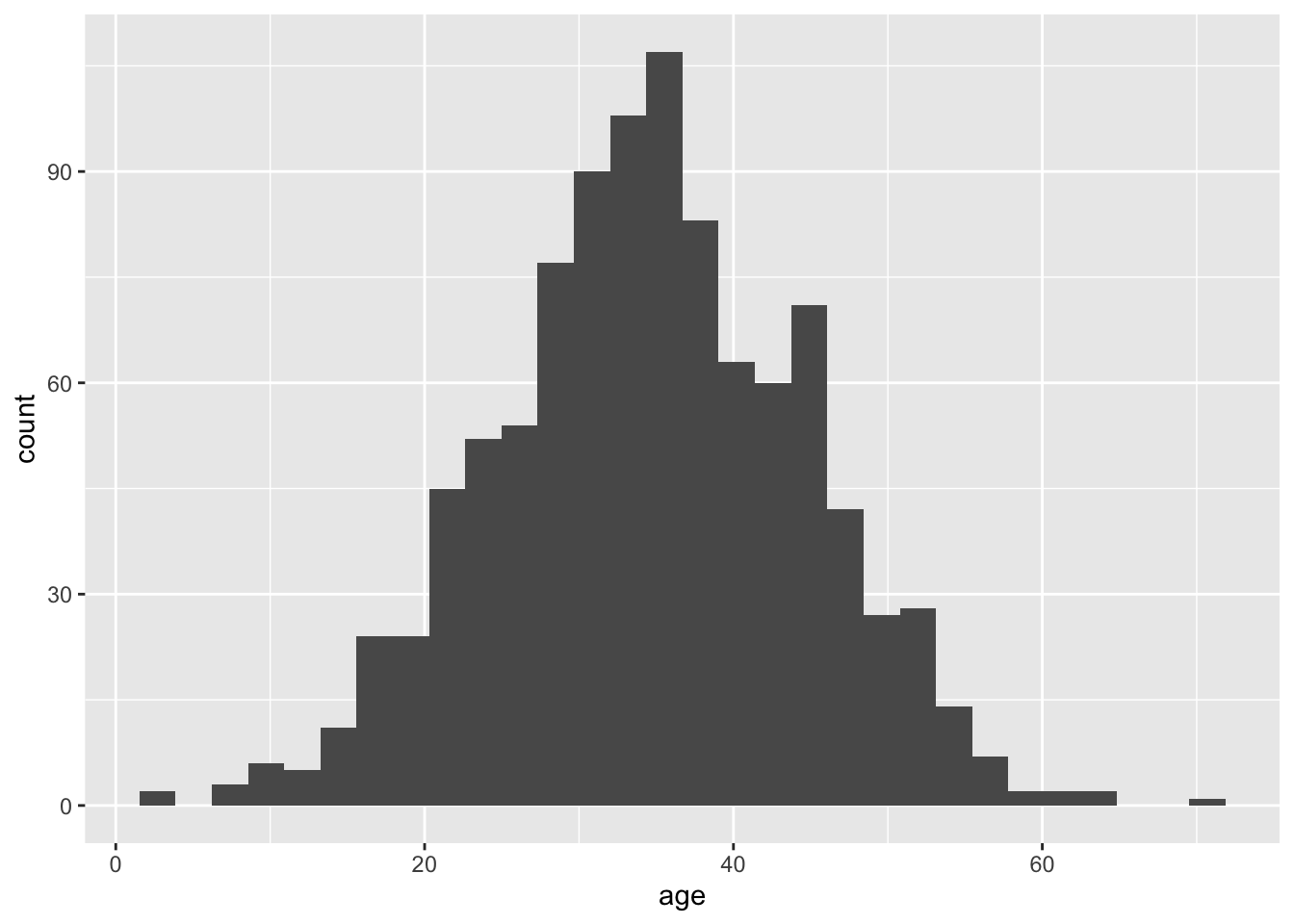

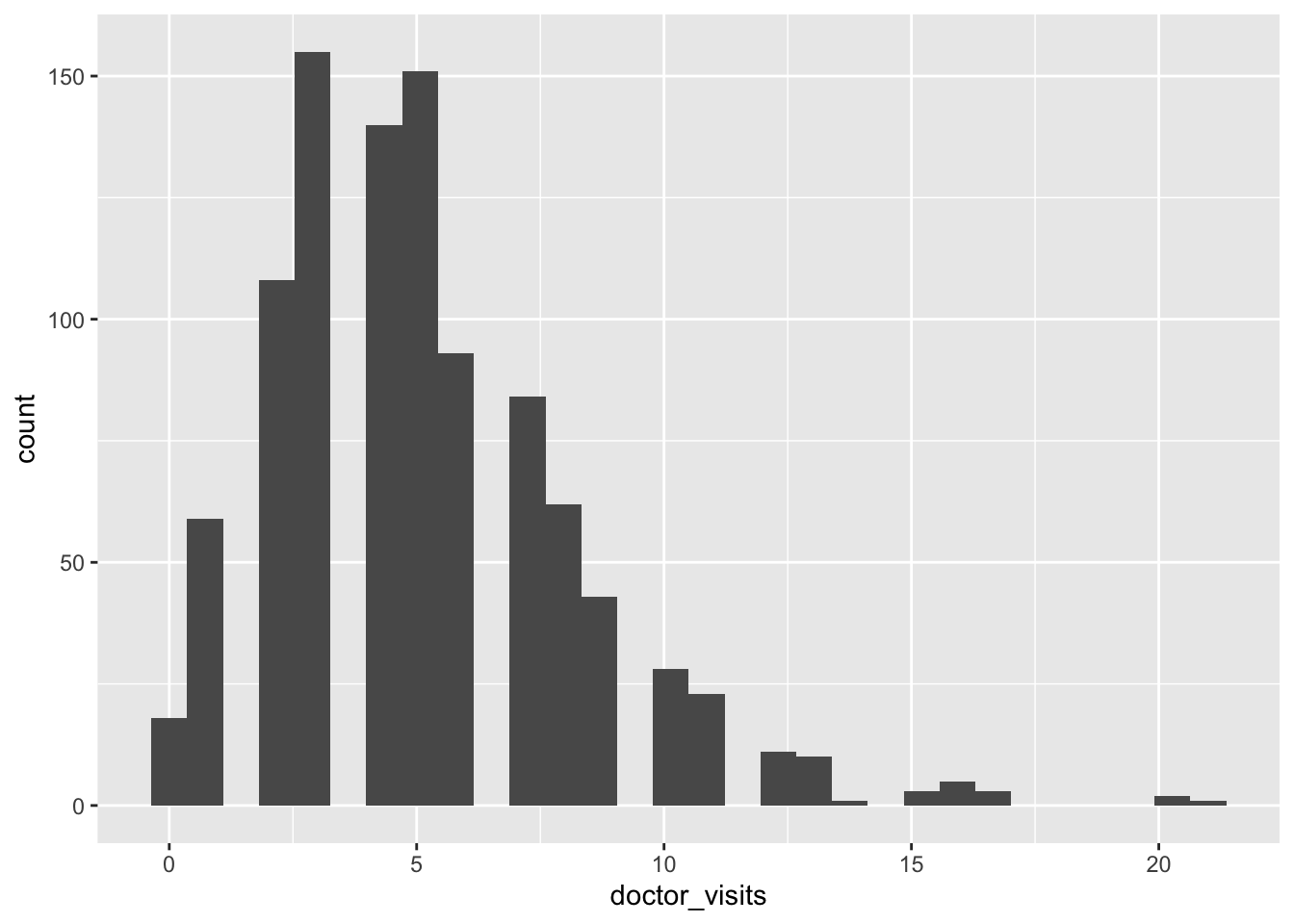

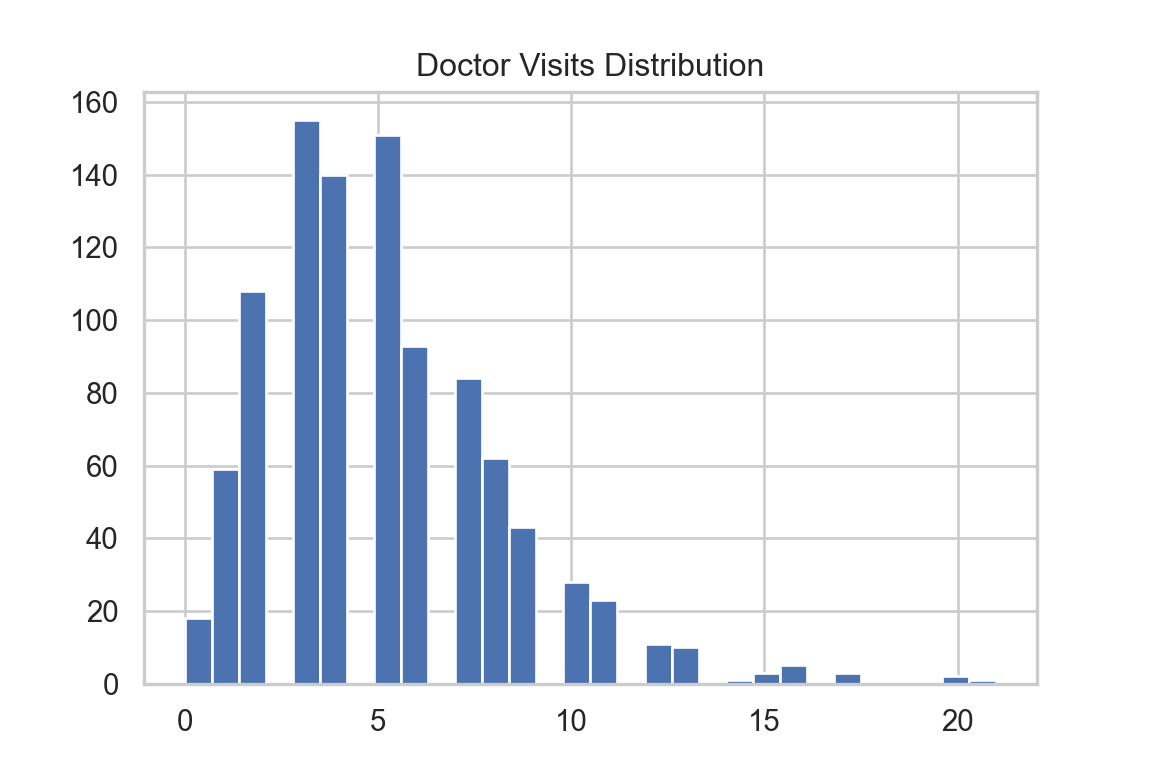

- The outcome variable is discrete and count-type as shown in Figure 10.1. Examples include number of doctor visits, number of web clicks, number of accidents, etc.

- Outcomes are statistically independent from one to the next.

- The mean and variance of the counts is approximately equal (i.e., there is equidispersion).

- Counts occur over fixed and known exposures (such as time intervals or geographic areas).

- We intend to use the logarithm of the mean of the outcome as a link function, which ensures that our predictions are always positive.

However, Classical Poisson regression should not be used in the following scenarios:

- The outcome is not a count (e.g., binary outcomes, proportions, or continuous variables).

- The data shows overdispersion (i.e., the variance exceeds the mean). In this case, check Negative Binomial or Generalized Poisson regressions.

- The data shows underdispersion (i.e., the variance is less than the mean), which Poisson regression cannot accommodate. Alternatively, check Generalized Poisson regression.

- The outcome variable includes a large number of zeros. Instead, check Zero-Inflated Poisson regression.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Describe the reason that ordinary linear models is inappropriate to use.

- Determine when Poisson regression is an appropriate modeling choice.

- Write down the likelihood function of a Poisson regression models.

- Understand the computation procedure of the Poisson regression coefficient estimation.

- Interpret the Poisson regression coefficients in the real scenarios.

- Evaluate model performance and construct confidence intervals.

10.1 Introduction

This chapter introduces a generalized linear regression model that can be applied on Poisson-distributed count data. Compared to ordinary regression, which assume normality and constant variance—homoskedasticity, Poisson regression models count data that is skewed and heteroskedastic.

Some research questions you might explore using Poisson regression:

- How is the number of insurance claims filed by policyholders in a year associated with ages, vehicle types, and regions?

- How can the number of complaints received by a telecom company from customers be explained by service types and contract lengths?

- How does the distribution of counts of satellite male horseshoe crabs residing around a female horseshoe crab nest vary by the phenotypic characteristics of the female horseshoe crabs?

10.1.1 Poisson Regression Assumptions

Independence: Poisson regression assumes the responses to be counts–(nonnegative integers: 0, 1, 2,…). Each response is mutually independent to each other with mean parameter \(\lambda_i,i=1,\dots,n\).

Log-linearity: Poisson regression models the log-link function of the response as a linear combination of the explanatory variables, i.e., \(\log(\lambda_i) = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X_{i1}+\dots+\beta_p X_{ip}\) with \(\lambda_i> 0\) for all \(i=1,\dots,n\).

Heteroskedasticity: Poisson regression assumes heteoroskedastic response, i.e., the variance of the response increases along with the mean increasing; in contrast to the ordinary regression with Gaussian noise, whose the variance is constant and independent to the mean. Poisson regression assumes equidispersion, i.e., the variance is the same as the expectation of the response; compared to overdispersion in negative binomial distribution where the variance is greater than the mean.

10.1.2 A Graphical Look

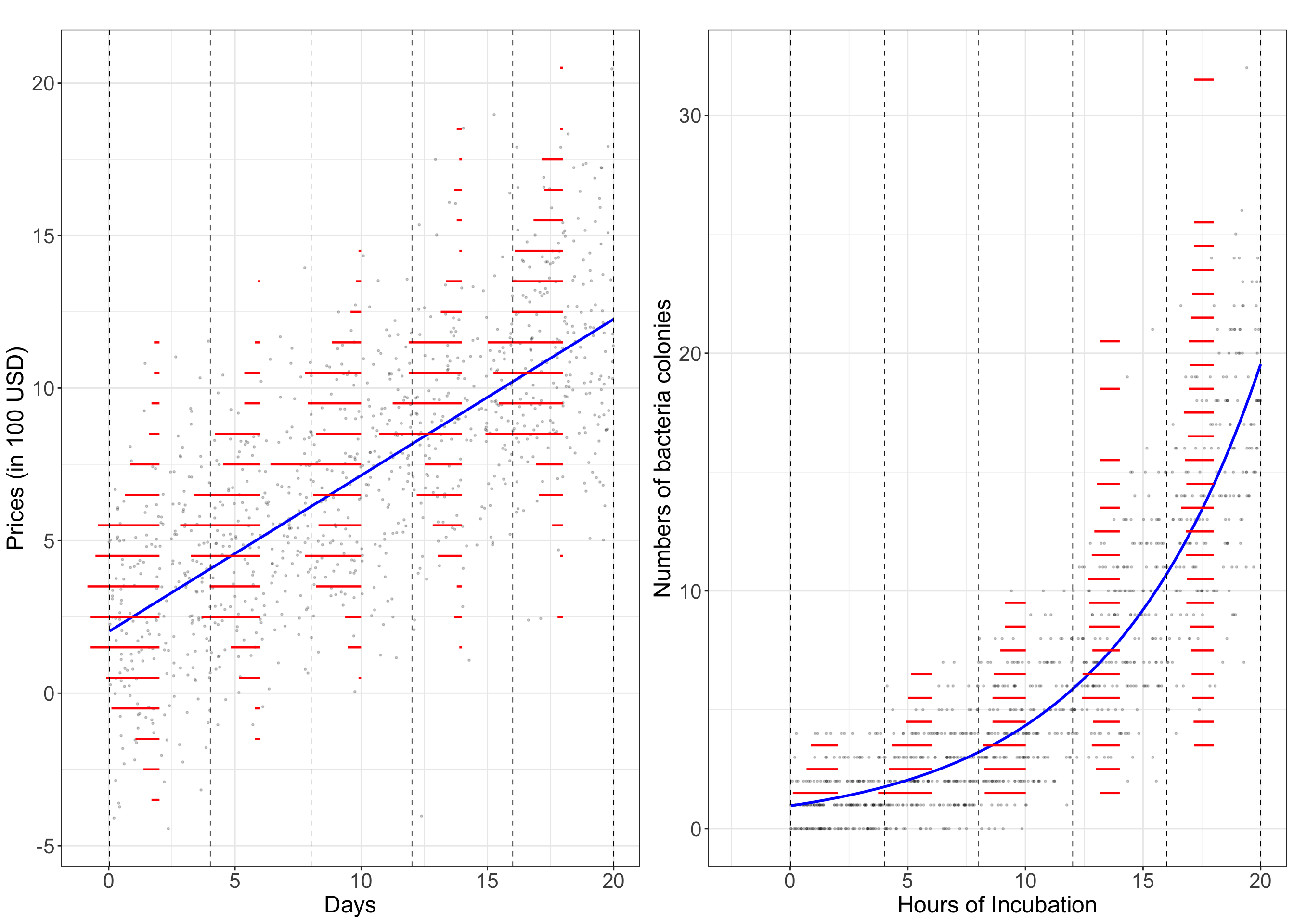

Below is a graphical demonstration of the comparison between the ordinary linear regression with Gaussian distributed response and Poisson regression with Poisson distributed response. The left panel illustrates the price of smartphones (in 100 USD) increase with the number of days listed on an online marketplace. The right panel illustrates the number of bacteria colonies on a petri dish versus the hours of incubation.

The ordinary linear regression has a linear fitted blue line (in the left panel), while the Poisson regression, due to the use of log-link function, has a fitted blue curve (in the right panel). Segment the explanatory variable (in the x axis) in each scenario into five sections using the gray dashed vertical lines. The red horizontal segments represent the frequencies of binned response in each section, which represents the rotated histogram of the response. In ordinary linear regression, the response in each section is symmetrically distributed with similar variation across five sections (i.e., homoskedasticity); while in Poisson regression, the response is skewed with heteroskedasticity (specifically, increasing variances as the responses increase) across sections.

10.2 Case Study: Horseshoe Crab Satellites

Let’s take a closer look at the example in the third question mentioned in the Introduction—exploring the differential distribution of the number of satellite male horseshoe crabs residing around a female horseshoe crab nest across various phenotypic characteristics. Using the dataset crabs provided by Brockmann, 1996, let’s load the dataset and do some data wrangling.

10.3 Data Collection and Wrangling

There are 173 records of the female horseshoe crab nests and their male satellites with 5 features: satell: satellite size of each nest (i.e., the number of male horseshoe crabs around each female horseshoe crab nest), width: shell width in cm, color: 1 = medium light, 2 = medium, 3 = medium dark, 4 = dark, spine: spine condition: 1 = both good, 2 = one broken, 3 = both broken, and weight: weight in kg (referring to Section 3.3.3 in Agresti, 2018).

# A tibble: 173 × 5

satell width color spine weight

<int> <dbl> <fct> <fct> <dbl>

1 8 28.3 2 3 3.05

2 0 22.5 3 3 1.55

3 9 26 1 1 2.3

4 0 24.8 3 3 2.1

5 4 26 3 3 2.6

6 0 23.8 2 3 2.1

7 0 26.5 1 1 2.35

8 0 24.7 3 2 1.9

9 0 23.7 2 1 1.95

10 0 25.6 3 3 2.15

# ℹ 163 more rowssatell int64

width float64

color category

spine category

weight float64

dtype: object| satell | width | color | spine | weight | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 8 | 28.3 | 2 | 3 | 3.050 |

| 1 | 0 | 22.5 | 3 | 3 | 1.550 |

| 2 | 9 | 26.0 | 1 | 1 | 2.300 |

| 3 | 0 | 24.8 | 3 | 3 | 2.100 |

| 4 | 4 | 26.0 | 3 | 3 | 2.600 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 168 | 3 | 26.1 | 3 | 3 | 2.750 |

| 169 | 4 | 29.0 | 3 | 3 | 3.275 |

| 170 | 0 | 28.0 | 1 | 1 | 2.625 |

| 171 | 0 | 27.0 | 4 | 3 | 2.625 |

| 172 | 0 | 24.5 | 2 | 2 | 2.000 |

173 rows × 5 columns

Let’s now split the data into training and test sets.

# Use 70% data for training and 30% for testing

par <- 0.7

# Set seed for reproducible splitting

set.seed(1046)

n <- nrow(crabs)

train_indices <- sample(seq_len(n), size = floor(par * n))

# Create training and test sets

train_set <- crabs[train_indices, ]

test_set <- crabs[-train_indices, ]

# Print the number of training and test samples

cat("Number of training samples:", nrow(train_set), "\n")

cat("Number of test samples:", nrow(test_set), "\n")# Use 70% data for training and 30% for testing

par = 0.7

# Set seed for reproducible splitting

np.random.seed(1046)

n = len(crabs)

train_indices = np.random.choice(n, size=int(par * n), replace=False)

# Create training and test sets

train_set = crabs.iloc[train_indices]

test_set = crabs.drop(index=train_indices)

# Print the number of training and test samples

print(f"Number of training samples: {len(train_set)}")

print(f"Number of test samples: {len(test_set)}")Number of training samples: 122 Number of test samples: 51 Number of training samples: 122Number of test samples: 5110.4 Exploratory Data Analysis

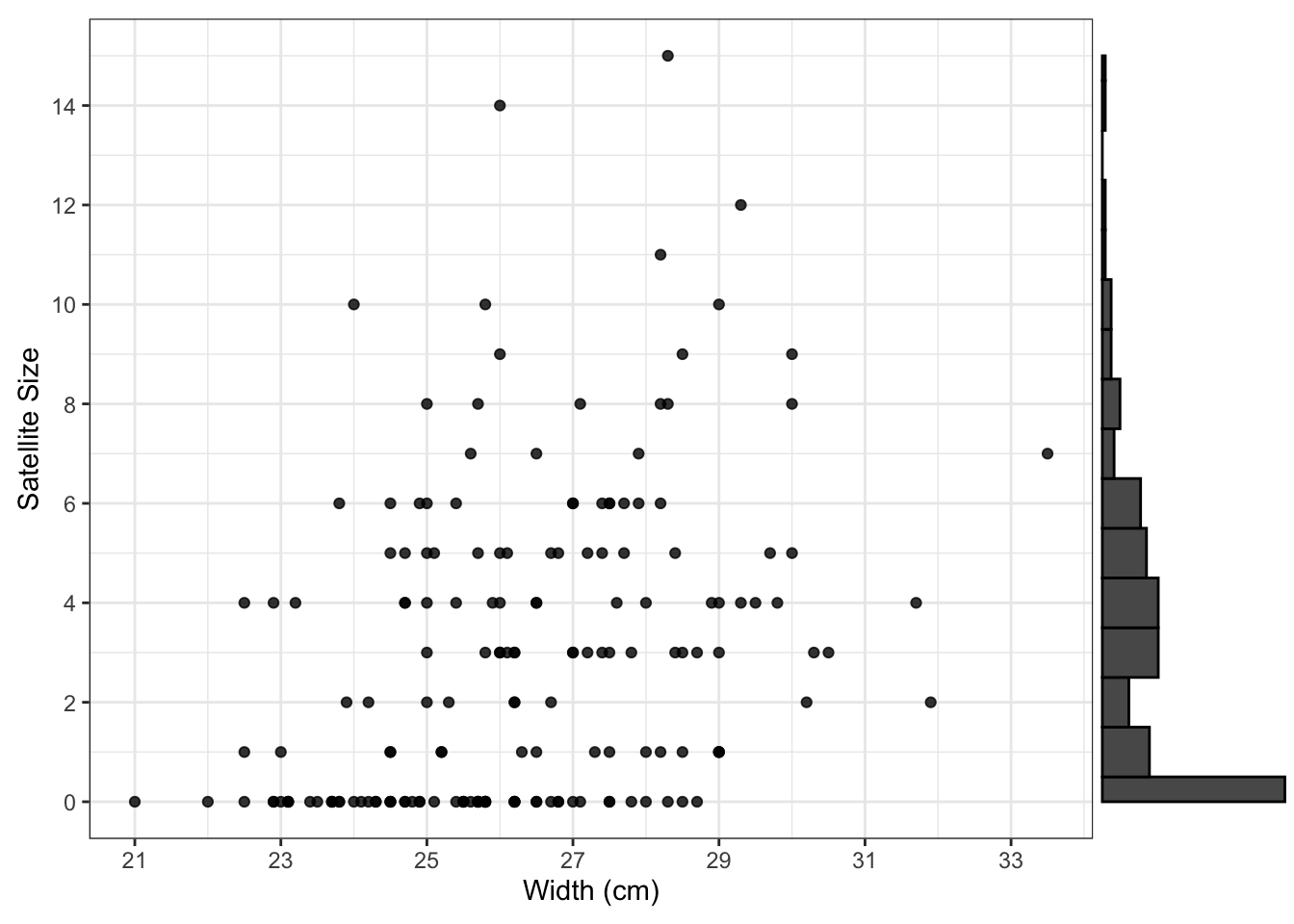

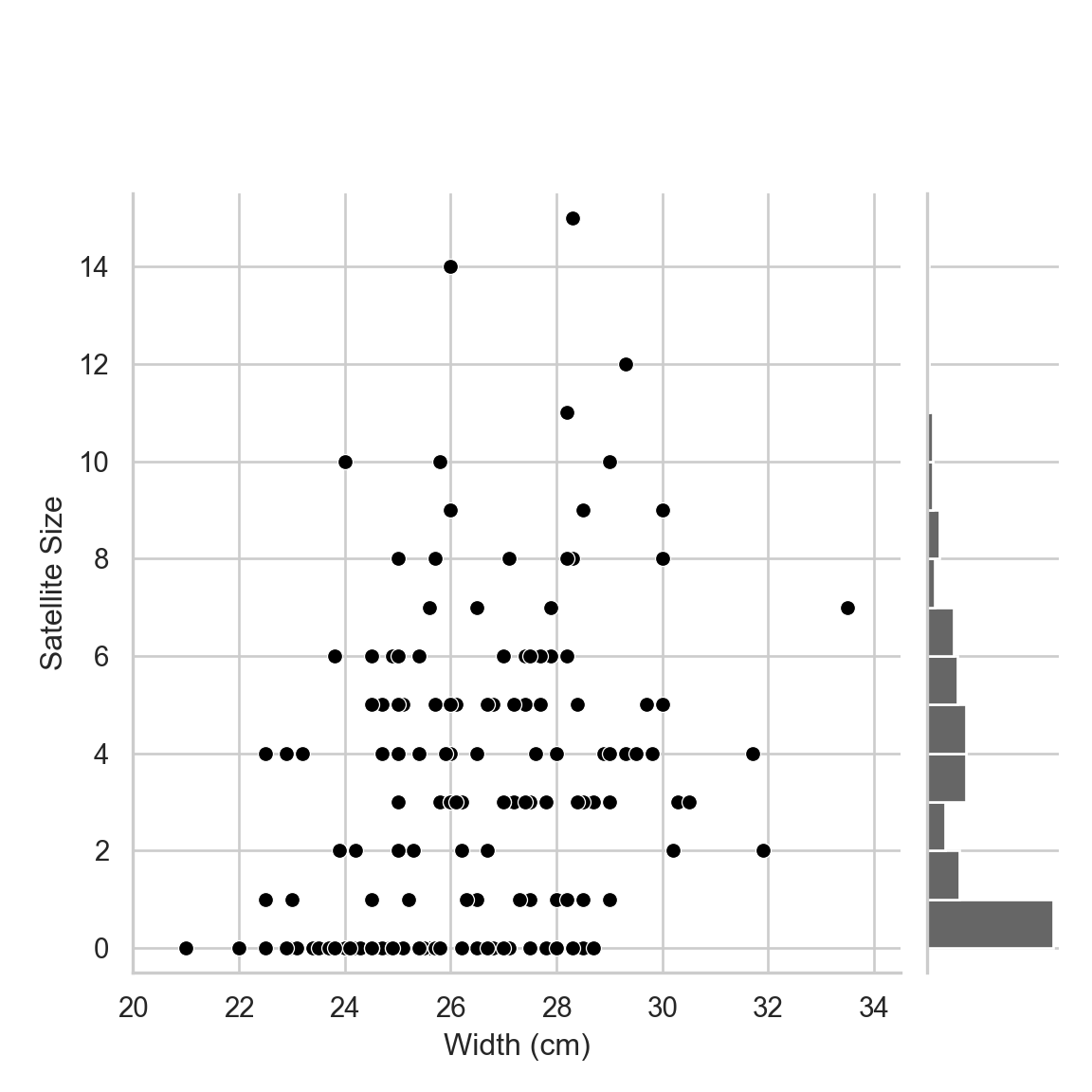

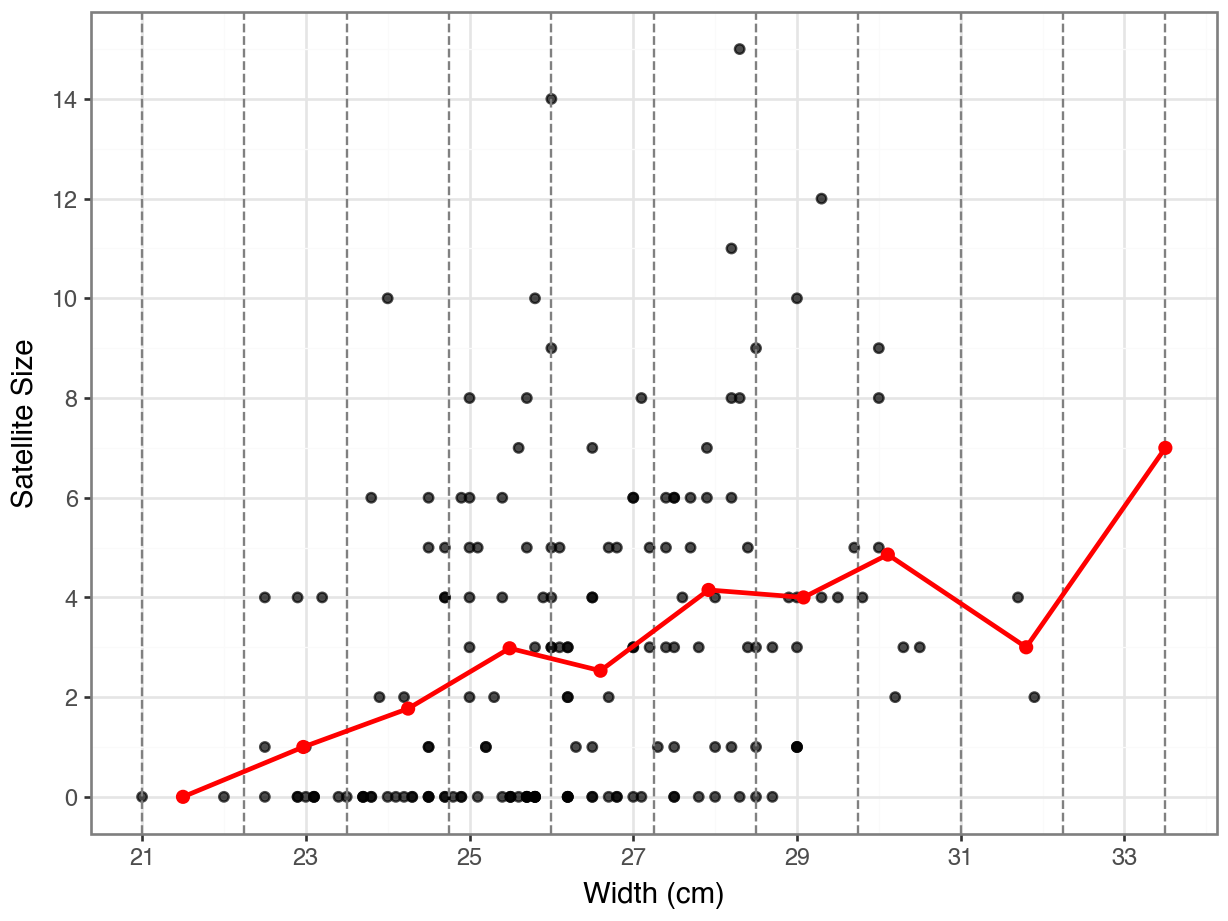

Suppose that the relationship between the satellite size per nest (satell) and width of the female horseshoe crab (width in cm) is our main research interest. Let’s explore their relationship in the following scatterplot with the distribution of satell on the margin.

# draw the scatterplot of satellite size versus width

p <- crabs %>%

ggplot(aes(y = satell, x = width)) +

geom_point(alpha = 0.8) +

labs(x = "Width (cm)", y = "Satellite Size") +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = seq(floor(min(crabs$width)), ceiling(max(crabs$width)), by = 2)) +

scale_y_continuous(breaks = scales::pretty_breaks(n = 10)) +

theme_bw()

# add a marginal histogram with binwidth of 1, i.e., bins for integers; equivalent to the barplot

ggMarginal(p, type = "histogram", margins = "y", binwidth = 1, boundary = -0.5) # start with `satell=-0.5` to avoid the first bins (0s and 1s) being combined in one binimport seaborn as sns

sns.set(style = "whitegrid")

# create bins of width 1 for the marginal histogram

bin_edges = np.arange(crabs['satell'].min(), crabs['satell'].max() + 2, 1) # bins of width 1

# draw the scatterplot of satellite size versus width with marginal distributions

g = sns.jointplot(

data = crabs,

x = "width",

y = "satell",

color = "black",

kind = "scatter",

marginal_ticks = False,

marginal_kws = dict(bins = bin_edges, fill = True, color="black", alpha=0.6)

)

g.ax_marg_x.remove() # remove the marginal histogram on x axis

# add labels

g.ax_joint.set_xlabel("Width (cm)")

g.ax_joint.set_ylabel("Satellite Size")

# add axes' limits

ymin, ymax = crabs['satell'].min(), crabs['satell'].max()

xmin, xmax = crabs['width'].min(), crabs['width'].max()

g.ax_joint.set_xlim(xmin - 1, xmax + 1);

g.ax_joint.set_ylim(ymin - 0.5, ymax + 0.5);

g.ax_marg_y.set_ylim(ymin - 0.5, ymax + 0.5);

The distribution of satellite sizes is highly right skewed, which violates the normality assumption of the ordinary linear regression.

In the scatter plot above, we can tell that the satellite size gets more spread out as the width increases. The averaged satellite sizes turn to increase along the width increasing. Let’s now split the width into a few intervals and compute the representative point for each interval to have a clear look at the trend.

# set up the number of intervals

n_intervals <- 10

# compute the average points for each interval of `width`

crabs_binned <- crabs %>%

mutate(width_inl = cut(width, breaks = n_intervals)) %>%

group_by(width_inl) %>%

summarize(

mean_width = mean(width),

mean_satell = mean(satell),

.groups = "drop"

)

crabs_binned# set up the number of intervals

n_intervals = 10

# compute the average points for each interval of `width`

crabs['width_inl'] = pd.cut(crabs['width'], bins=n_intervals)

crabs_binned = (

crabs

.groupby('width_inl', observed=True)

.agg(mean_width=('width', 'mean'), mean_satell=('satell', 'mean'))

.reset_index()

.round(2)

)

crabs_binned# A tibble: 10 × 3

width_inl mean_width mean_satell

<fct> <dbl> <dbl>

1 (21,22.2] 21.5 0

2 (22.2,23.5] 23.0 1

3 (23.5,24.8] 24.2 1.77

4 (24.8,26] 25.5 2.98

5 (26,27.2] 26.6 2.53

6 (27.2,28.5] 27.9 4.15

7 (28.5,29.8] 29.1 4

8 (29.8,31] 30.1 4.86

9 (31,32.2] 31.8 3

10 (32.2,33.5] 33.5 7 | width_inl | mean_width | mean_satell | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | (20.988, 22.25] | 21.50 | 0.00 |

| 1 | (22.25, 23.5] | 22.97 | 1.00 |

| 2 | (23.5, 24.75] | 24.25 | 1.77 |

| 3 | (24.75, 26.0] | 25.49 | 2.98 |

| 4 | (26.0, 27.25] | 26.60 | 2.53 |

| 5 | (27.25, 28.5] | 27.92 | 4.15 |

| 6 | (28.5, 29.75] | 29.08 | 4.00 |

| 7 | (29.75, 31.0] | 30.11 | 4.86 |

| 8 | (31.0, 32.25] | 31.80 | 3.00 |

| 9 | (32.25, 33.5] | 33.50 | 7.00 |

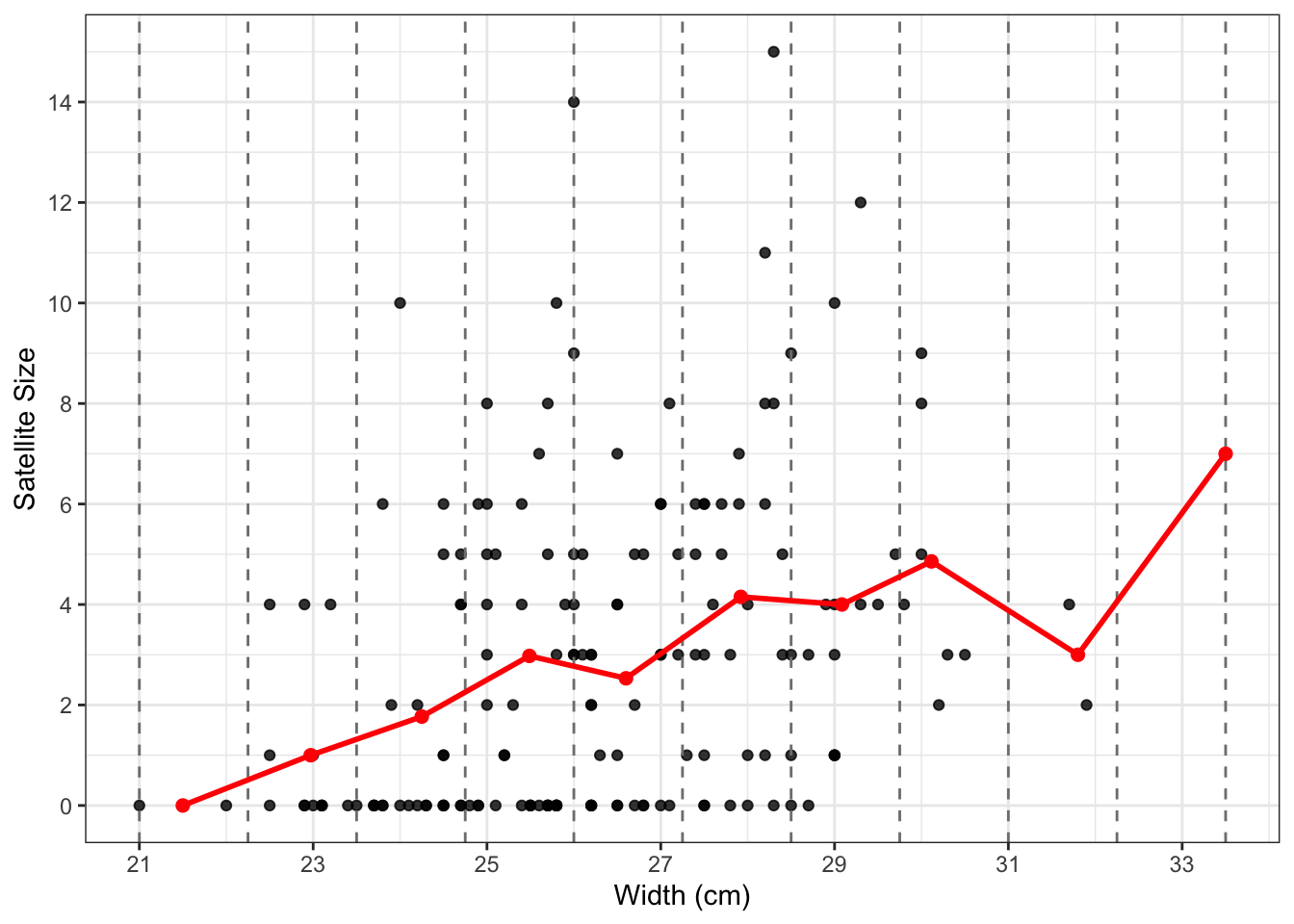

We’ve prepared the summarized dataset for the average points—each entry includes an interval of width, an averaged width, and an averaged satellite size per interval. Now, let’s visualize the representative points on the scatter plot to take a closer look at the trend.

# add the average points onto the scatterplot, connect them, and mark intervals

breaks <- seq(min(crabs$width), max(crabs$width), length.out = n_intervals + 1)

p +

geom_vline(xintercept = breaks, linetype = "dashed", color = "gray50") +

geom_point(data = crabs_binned, aes(x = mean_width, y = mean_satell), color = "red", size = 2) +

geom_line(data = crabs_binned, aes(x = mean_width, y = mean_satell), color = "red", linewidth = 1)# draw the scatterplot of satellite size versus width

p = (

ggplot(crabs, aes(x='width', y='satell')) +

geom_point(alpha=0.7, color='black') + # points in gray

labs(x="Width (cm)", y="Satellite Size") +

scale_x_continuous(breaks=range(int(np.floor(crabs['width'].min())), int(np.ceil(crabs['width'].max())) + 1, 2)) +

scale_y_continuous(breaks=range(int(np.floor(crabs['satell'].min())), int(np.ceil(crabs['satell'].max())) + 1, 2)) +

theme_bw()

)

# add the average points onto the scatterplot, connect them, and mark intervals

breaks = np.linspace(crabs['width'].min(), crabs['width'].max(), n_intervals + 1)

p_final = (

p +

geom_vline(xintercept=breaks, linetype='dashed', color='gray') +

geom_point(data=crabs_binned, mapping=aes(x='mean_width', y='mean_satell'), color='red', size=2) +

geom_line(data=crabs_binned, mapping=aes(x='mean_width', y='mean_satell'), color='red', size=1)

)

p_final.show()

We can see a general increasing trend of the satellite size as the nest width grows.

10.5 Data Modelling

The Poisson regression model assumes a random sample of \(n\) count observations \(Y_i\)s, hence independent (but not identically distributed!), which have the following distribution: \[Y_i \sim \mathrm{Poisson}(\lambda_i).\] Each \(i\)th observation has its own \(\mathbb{E}(Y_i)=\lambda_i>0\), which also implicates \(Var(Y_i)=\lambda_i>0\).

Parameter \(\lambda_i\) is the risk of an event occurrence, coming from the definition of the Poisson random variable, in a given timeframe or even a space. It is a continuous distributional parameter! For the crabs dataset, the events are the number of satellite male horseshoe crabs around a space: the female breeding nest.

Since the Poisson Regression model is also a GLM, we need to set up a link function for the mean. Let \(X_{i,\text{width}}\) be the \(i\)th value for the regressor width in our dataset. An easy modelling solution would be an identity link function as in \[

h(\lambda_i)=\lambda_i=\beta_0+\beta_1 X_{i,\text{width}}. \label{eq:pois-uni-iden}

\]

However, we have a response range issue!

The model (eq:pois-uni-iden?) for has a significant drawback: the right-hand side is allowed to take on even negative values, which does not align with the nature of the parameter \(\lambda_i\) (that always has to be non-negative).

Recall the essential characteristic of a GLM that should come into play for a link function. In this class of models, the direct relationship between the original response and the regressors may be non-linear as in \(h(\lambda_i)\). Hence, instead of using the identity link function, we will use the natural logarithm of the mean: \(\log(\lambda_i)\).

Before continuing with the crabs dataset, let us generalize the Poisson regression model with \(k\) regressors as: \[ h(\lambda_i) = \log(\lambda_i)=\beta_0+\beta_1 X_{i,1}+\dots+\beta_k X_{i,k}. \label{eq:pois-k} \] We could make more sense in the interpretation by exponentiating (eq:pois-k?): \[ \lambda_i = \exp(\beta_0+\beta_1 X_{i,1}+\dots+\beta_k X_{i,k}), \label{eq:pois-k-exp} \] where an increase in one unit in any of the \(k\) regressors (while keeping the rest of them constant) multiplies the mean \(\lambda_i\) by a factor \(\exp(\beta_j)\), for all \(j=i,\dots,k\).

In the crabs dataset with width as a regressor, the Poisson regression model is depicted as: \[

\log(\lambda_i)=\lambda_i=\beta_0+\beta_1 X_{i,\text{width}}. \label{eq:pois-uni}

\]

10.6 Estimation

In generalized linear models (GLMs), parameter estimation is typically performed using maximum likelihood estimation (MLE). A widely used algorithm to compute the MLE in GLMs is the iteratively reweighted least squares (IRLS) method, which learns the regression coefficients by solving the weighted least squares problems through iteration. Below we learn the essential elements of the IRLS method and the MLE that it solves. We use Poisson regression as an example, but the procedure applies to other distributions straightforwardly.

The general idea to solve the generalized linear regression is to estimate the parameters by maximizing the likelihood. For Poisson regression in (eq:pois-k?) specifically, it is written as: \[ \prod_{i=1}^n p_{Y_i}(y_i) = \prod_{i=1}^n \frac{e^{-\lambda_i}{\lambda_i}^{y_i}}{y_i!}, \] where \(p_{Y_i}(y_i)\) is the probability mass function of \(Y_i\), for \(i=1,\dots,n\).

Let \(\boldsymbol{\beta}:=(\beta_0,\dots,\beta_k)^{\top}\) be the coefficient vector, and then (eq:pois-k-exp?) can be rewritten as \(\lambda_i=\exp(X_{i}^{\top}\boldsymbol{\beta})\), where \(X_{i}^{\top}\) is the row \(i\) in the design matrix \(X\). Maximizing the likelihood is equivalent to minimizing the log-likelihood in terms of solving for the parameters \(\beta_j,j=1,\dots,k\): \[ {\arg\min}_{\boldsymbol{\lambda}} - \prod_{i=1}^n\frac{e^{-\lambda_i}{\lambda_i}^{y_i}}{y_i!} = {\arg\min}_{\boldsymbol{\lambda}} \sum_{i=1}^n \lambda_i - y_i \log(\lambda_i). \] Plugging in \(\lambda_i=\exp(X_{i}^{\top}\boldsymbol{\beta})\) gives the minimization problem with respect to the Poisson regression coefficients: \[ {\arg\min}_{\boldsymbol{\beta}} \sum_{i=1}^n \exp(X_{i}^{\top}\boldsymbol{\beta}) - y_i X_{i}^{\top}\boldsymbol{\beta}. \label{eq:pois-log} \]

Since the objective in (eq:pois-log?) is not quadratic and there is no closed form solution, we could not solve the equation exactly. IRLS solves an approximated solution with a specified accuracy or tolerance. The basic idea is that IRLS uses Fisher scoring (or Newton-Raphson) to solve an approximated problem of the original objective (eq:pois-log?) and solve it iteratively with weights updated through iteration until the specified accuracy is achieved, i.e., the objective is converged.

The MLE \(\hat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}\) satisfies the score function \(U(\boldsymbol{\beta}) = \nabla_{\boldsymbol{\beta}} \ell(\boldsymbol{\beta}) = 0\). Applying the Fisher scoring update gives: \[ \boldsymbol{\beta}^{t+1} \leftarrow \boldsymbol{\beta}^{t} + {\mathcal{I}(\boldsymbol{\beta}^t)}^{-1} U(\boldsymbol{\beta}^{t}), \] where \(\mathcal{I}(\boldsymbol{\beta}^t) := \mathbb{E}\big[- \nabla^2_{\boldsymbol{\beta}} \ell(\boldsymbol{\beta}^t)\big]\) is the Fisher information, which is the expectation of the negative second-order derivative of the log-likelihood with respect to the parameters.

The Fisher scoring update corresponds to solve the following approximated problem of the original objective at iterate \(t+1\), which is a weighted least squares problem written as: \[

\begin{align}

\boldsymbol{\beta}^{t+1} &= {\arg\min}_{\boldsymbol{\beta}} \sum_{i=1}^n w_i^t (y_i^t - X_i^{\top}\boldsymbol{\beta})^2 \\

&= {\arg\min}_{\boldsymbol{\beta}} \sum_{i=1}^n w_i^t (y_i^t - \beta_0 - \beta_1 x_{i,\text{width}})^2 \label{eq:irls-approx}

\end{align}

\] given the estimates at time \(t\) for the univariate case using crabs dataset. The approximated problem has a closed-form solution and is much easier to solve than the original objective. The observations \(y_i\) and weights \(w_i\) should be updated per iterate. The arbitrary observations \(y_i^{t+1}\) is a function of the original observations \(y_i^0\) and the coefficient estimates. The weights is updated by \[w_i^{t+1} = \Big(\frac{1}{Var(Y_i)}\Big)\Big(\frac{1}{g'(\lambda_i)}\Big)^2,\] where \(\lambda_i\) is the mean of the response \(y_i\), \(\eta_i=g(\lambda_i)\) is the link function of the mean. In our case, the weights at iterate \(t+1\) can be updated given the coefficient estimates at \(t\) using the following formula: \[

w_i^{t+1} = \exp(X_i^{\top} \boldsymbol{\beta}^t), \forall i=1,\dots,n.

\]

The IRLS iteration procedure is as follows.

- Choose a set of initial coefficients \(\boldsymbol{\lambda}^0 = (\lambda_0^0,\dots,\lambda_k^0)\), which can be a vector of zeros.

- Compute the weights based on the estimates from the previous iterate, or the inital coefficients at the first iterate.

- Solve the approximated problem (irls-approx?).

- Check te convergence condition.

- Return estimates if the objective is converged; go back to step 2 if not.

Let’s now fit the model on the training data.

# Fit Poisson regression

poisson_model = glm(formula='satell ~ width', data=train_data, family=sm.families.Poisson(link=sm.families.links.log())).fit()

# View summary

print(poisson_model.summary())

Call:

glm(formula = satell ~ width, family = poisson(link = "log"),

data = train_set)

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

(Intercept) -3.43023 0.64716 -5.300 1.16e-07 ***

width 0.16973 0.02386 7.112 1.14e-12 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

(Dispersion parameter for poisson family taken to be 1)

Null deviance: 476.83 on 121 degrees of freedom

Residual deviance: 428.20 on 120 degrees of freedom

AIC: 679.01

Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 6 Generalized Linear Model Regression Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: satell No. Observations: 122

Model: GLM Df Residuals: 120

Model Family: Poisson Df Model: 1

Link Function: log Scale: 1.0000

Method: IRLS Log-Likelihood: -337.50

Date: Wed, 18 Feb 2026 Deviance: 428.20

Time: 22:23:39 Pearson chi2: 418.

No. Iterations: 5 Pseudo R-squ. (CS): 0.3287

Covariance Type: nonrobust

==============================================================================

coef std err z P>|z| [0.025 0.975]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Intercept -3.4302 0.647 -5.300 0.000 -4.699 -2.162

width 0.1697 0.024 7.112 0.000 0.123 0.216

==============================================================================10.7 Goodness of Fit

In GLMs, we can use residual deviance and Chi-squared test to check the goodness of fit of the model. The residual deviance measures how well the fitted model explains the observed outcomes, compared to a perfect model (the saturated model) that explains the data exactly. A smaller residual deviance means a better fit of the data. It is computed as \[\text{Residual Deviance } = 2 (\ell_{\mathrm{saturated}} - \ell_{\mathrm{fitted}}),\] where \(\ell_A\) is the log-likelihood of model \(A\). For Poisson regression specifically, the residual deviance is \(2\sum_{i=1}^n \Big[y_i\log\big(\frac{y_i}{\hat{\lambda}_i}\big) - (y_i-\hat{\lambda}_i)\Big]\).

When the model is a good fit, the residual deviance is expected to follow a chi-squared distribution with degrees of freedom \(df = n - p\), where \(n\) is the number of observations and \(p\) is the number of parameters, asymptotically for a large enough sample size. We then can compute the \(p\)-value using the chi-squared distribution: \[ p\text{-value} = 1-P(\chi^2_{\mathrm{df}} \leq \text{residual deviance}). \]

\(p\)-value is the probability of observing a residual deviance as large as (or larger than) what we got, if the model is truly correct. A large p-value (e.g., > 0.05) means that the observed deviance is not surprisingly large. Out model is a good fit and could plausibly have generated the data. A small p-value (e.g., < 0.05) means that the deviance is too large to be due to chance. The model is a poor fit and likely missing something important.

# Residual deviance and degrees of freedom

res_dev <- deviance(poisson_model)

df_res <- df.residual(poisson_model)

# Chi-squared goodness-of-fit test

p_value <- 1 - pchisq(res_dev, df_res)

cat("Residual Deviance:", round(res_dev, 4), "\n")

cat("Degrees of Freedom:", df_res, "\n")

cat("Goodness-of-fit p-value:", round(p_value, 4), "\n")res_dev = poisson_model.deviance

df_res = poisson_model.df_resid

p_value = 1 - stats.chi2.cdf(res_dev, df_res)

print(f"Residual Deviance: {res_dev:.4f}")

print(f"Degrees of Freedom: {df_res}")

print(f"Goodness-of-fit p-value: {p_value:.4f}")Residual Deviance: 428.2018 Degrees of Freedom: 120 Goodness-of-fit p-value: 0 Residual Deviance: 428.2018Degrees of Freedom: 120Goodness-of-fit p-value: 0.0000The probability of observing a deviance as large as this if the model is truly correct (i.e., the goodness-of-fit \(p\)-value) is esentially 0, saying that there is significant evidence of lack-of-fit. There can be several reasons for lack-of-fit. The model is misspecified, e.g., it is missing important covariates or nonlinear effects. The link function might be incorrect, so that the model is systematically overestimate or underestimate the data. There can be outliers or influential points that inflate the deviance. The data might be overdispersed, so that the residual deviance is inflated by the large variance.

10.8 Inference

The estimated model can be used for two purposes: inference and prediction. In terms of inference, we use the fitted model to identify the relationship between the response and regressors. Wald’s test is a general method for hypothesis testing in maximum likelihood estimation (MLE), including generalized linear models (GLMs) like Poisson regression. It tests the hypotheses of the form: \[ \begin{align} H_0 &: \beta_j = 0, \\ H_a &: \beta_j \neq 0. \end{align} \] using the fact that \(\frac{\hat{\beta}_j}{SE(\hat{\beta}_j)} \sim \mathcal{N}(0,1)\) asymptotically under \(H_0\), where \(\beta_j\) is the \(j\)th estimated regression coefficient and \(SE(\hat{\beta}_j)\) is its corresponding variability which is reflected in the standard error of the estimate. This ratio is the Wald’s test statistic \[z_j = \frac{\hat{\beta}_j}{SE(\hat{\beta}_j)}\] that is used to determine the statistical significance of \(\hat{\beta}_j\) using the fact that the squared statistic asymptotically follows a one-degree-of-freedom chi-squared test, i.e., \[W_j = \Big(\frac{\hat{\beta}_j}{SE(\hat{\beta}_j)}\Big)^2\sim \chi_1^2.\]

Remark 1: A statistic like \(t_j=\frac{\hat{\beta}_j}{SE(\hat{\beta}_j)}\) in t test is referred to as a \(t\)-value. It assumes finite-sample normality—a student’s \(t\)-distribution under the null hypothesis with \(H_0\) with \(n-k-1\) degrees of freedom. It can only be used for linear models with normal errors. While the Wald’s test applies to any MLE (e.g., Poisson or logistic) to be used in any GLMs, and assumes asymptotic normality—standard normal or \(\chi^2\) distribution under \(H_0\).

Remark 2: Wald’s test is validate under several conditions: 1-large sample size, so that the test statistic is asymptotically normal, 2-regularity conditions for MLE, including differentiable likelihood, positive definite Fisher information, correctly specified model and parameter space, 3-well-estimated parameters, i.e., parameters are not near the bounaries, 4-stable and finite standard errors, and 5-no outliers or high leverage points.

We can obtain the corresponding \(p\)-values for each \(\beta_j\) associated to the Wald’s test statistic under the null hypothesis \(H_0\). The smaller the \(p\)-value, the stronger the evidence against the null hypothesis \(H_0\) in our sample. Hence, small \(p\)-values (less than the significance level \(\alpha\)) indicate that the data provides evidence in favour of association (or causation if that is the case) between the response variable and the \(j\)th regressor.

Similarly, given a specified \((1-\alpha)\times 100%\) level of confidence, we can construct confidence intervals for the corresponding true value of \(\beta_j\): \[\hat{\beta}_j \pm t_{\alpha/2,n-k-1} SE(\hat{\beta}_j),\] where \(t_{\alpha/2,n-k-1}\) is the upper \(\alpha/2\) quantile of the \(t\)-distribution with \(n-k-1\) degrees of freedom.

Let’s now compute the 95% confidence interval.

tidy(poisson_model, conf.int = TRUE) %>% mutate_if(is.numeric, round, 3)# Get coefficient table

summary_df = poisson_model.summary2().tables[1]

# Compute confidence intervals

conf_int = poisson_model.conf_int()

conf_int.columns = ['conf_low', 'conf_high']

# Combine with coefficient table

summary_df = summary_df.join(conf_int)

# Round all numeric columns to 3 decimals

summary_df = summary_df.round(3)

print(summary_df)# A tibble: 2 × 7

term estimate std.error statistic p.value conf.low conf.high

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 (Intercept) -3.43 0.647 -5.3 0 -4.70 -2.16

2 width 0.17 0.024 7.11 0 0.123 0.216 Coef. Std.Err. z P>|z| [0.025 0.975] conf_low conf_high

Intercept -3.43 0.647 -5.300 0.0 -4.699 -2.162 -4.699 -2.162

width 0.17 0.024 7.112 0.0 0.123 0.216 0.123 0.216Our sample gives us evidence to reject \(H_0\) (with a nearly-zero \(p\) value), which suggests that carapace width is statistically associated to the logarithm of the satellite size. Now, it is time to plot the fitted values coming from poisson_model to check whether it provides a positive relationship between width and the original scale of the response satell.

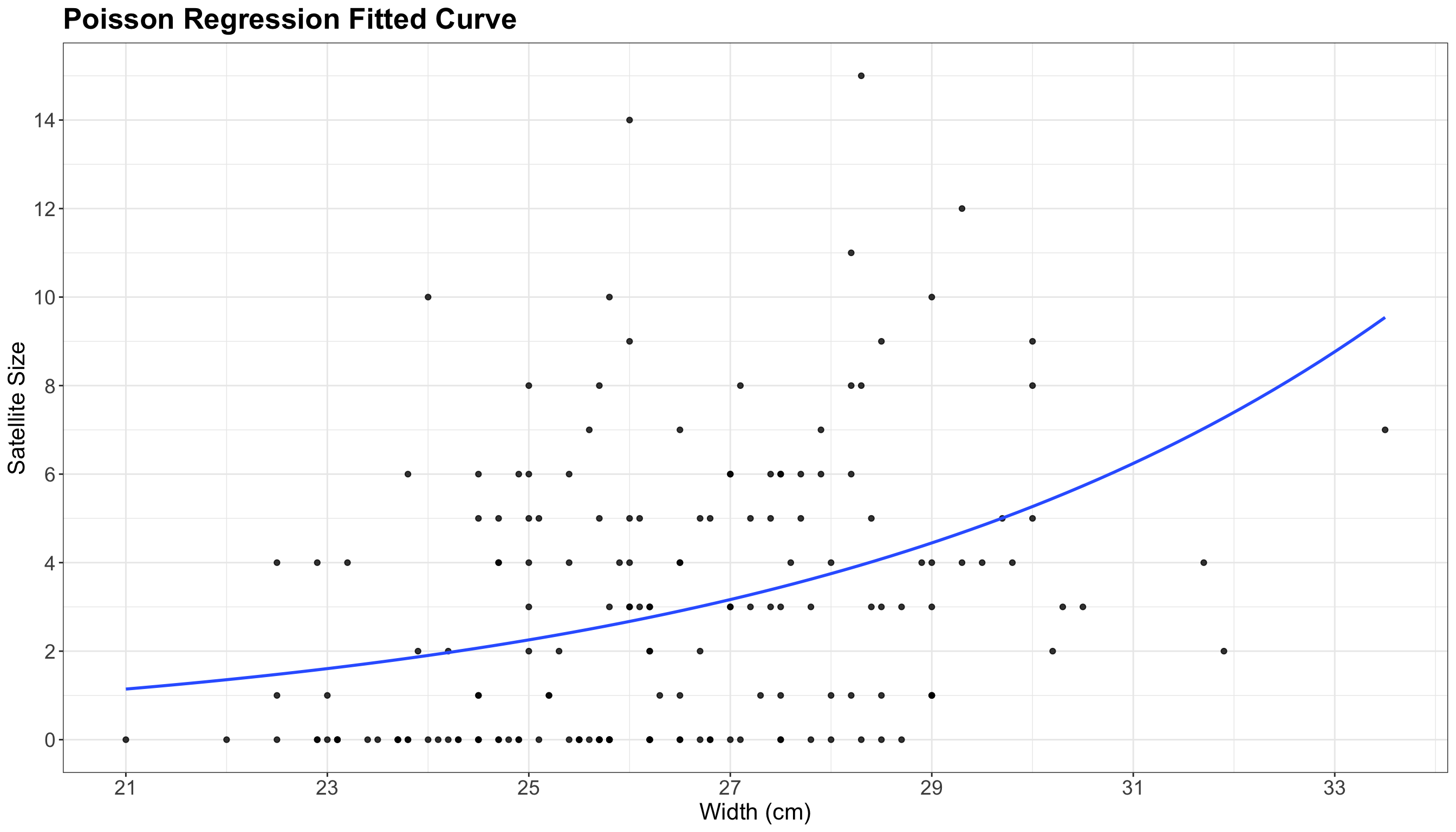

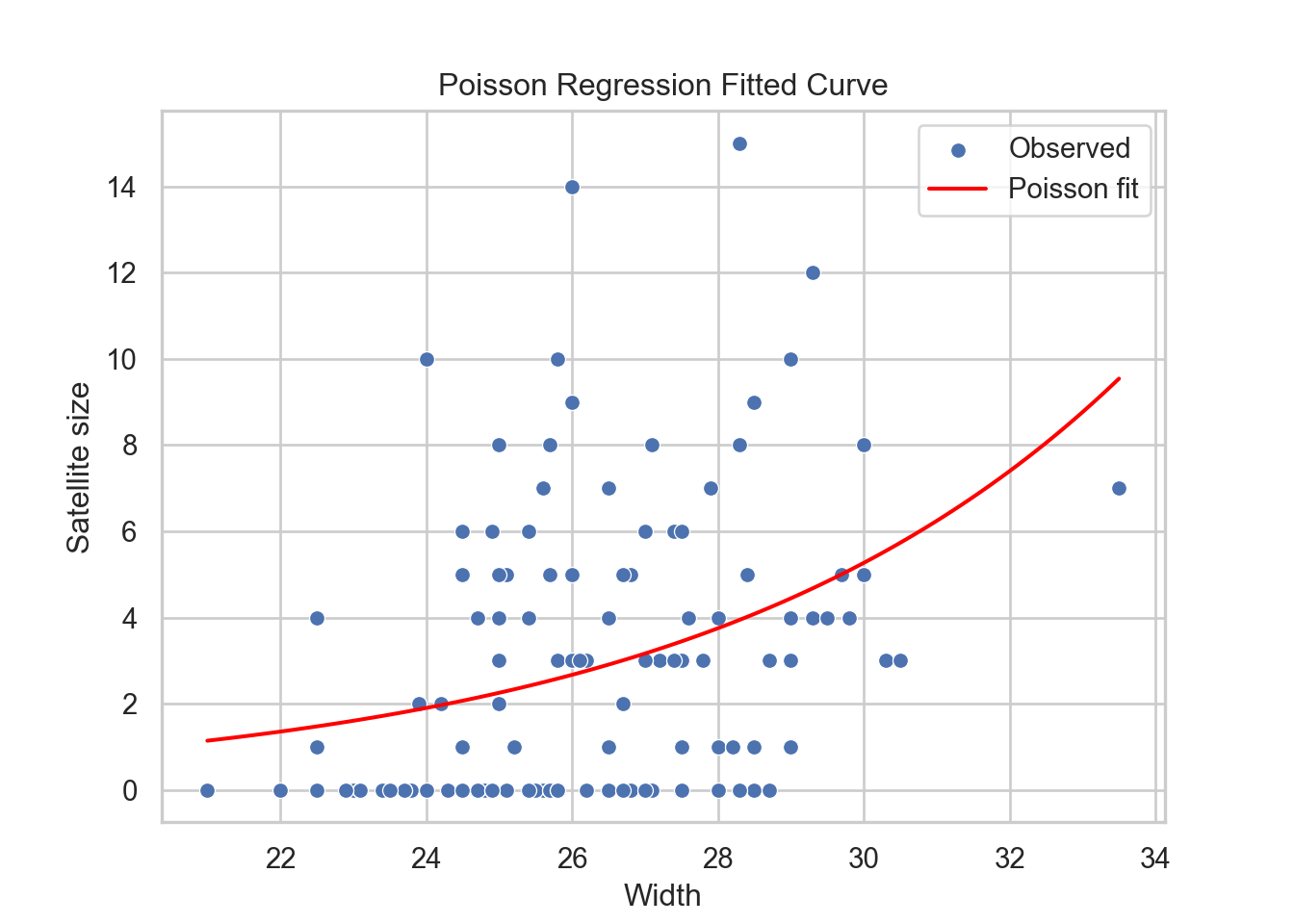

p +

geom_smooth(

data = train_set, aes(width, satell),

method = "glm", formula = y ~ x,

method.args = list(family = poisson), se = FALSE

) +

labs(title="Poisson Regression Fitted Curve")# Compute the fitted values

width_range = np.linspace(train_set['width'].min(), train_set['width'].max(), 100)

predict_df = pd.DataFrame({'width': width_range})

predict_df['predicted'] = poisson_model.predict(predict_df)

# Draw the scatterplot

sns.scatterplot(data=train_set, x='width', y='satell', label='Observed')

# Add the Poisson regression line

sns.lineplot(data=predict_df, x='width', y='predicted', color='red', label='Poisson fit')

# Add title

plt.title('Poisson Regression Fitted Curve')

plt.xlabel('Width')

plt.ylabel('Satellite size')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

The blue line in the plot above is the fitted Poisson regression of satell versus width. The positive relationship is now clear with this regression line.

10.9 Results

Let us fit a second model with two regressors: width (\(X_{\mathrm{width}_i}\)) and color (\(X_{\mathrm{color_2}_i}\), \(X_{\mathrm{color_3}_i}\), \(X_{\mathrm{color_4}_i}\)) for the \(i\)th observation: \[

h(\lambda_i) = \log(\lambda_i) = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X_{\mathrm{width}_i} + \beta_2 X_{\mathrm{color_2}_i} + \beta_3 X_{\mathrm{color_3}_i} + \beta_4 X_{\mathrm{color_4}_i}.

\] The explanatory variable color is of factor-type (discrete) and nominal (its levels do not follow any specific order). There are four levels: 1 = medium light, 2 = medium, 3 = medium dark, 4 = dark.

[1] "1" "2" "3" "4"Index([1, 2, 3, 4], dtype='int64')Using categorical variables such as color involves using dummy variables as in Binary Logistic regression. Taking the baseline 1 = medium light by default, this Poisson regression model will incorporate three dummy variables: \(X_{\mathrm{color_2}_i}\), \(X_{\mathrm{color_3}_i}\), and \(X_{\mathrm{color_4}_i}\). For different levels of color, these dummy variables take on the following values:

- When

coloris1 = medium light, then all three dummy variables \(X_{\mathrm{color_2}_i} = X_{\mathrm{color_3}_i} = X_{\mathrm{color_4}_i}=0\). - When

coloris2 = medium, then \(X_{\mathrm{color_2}_i}=1\) while the other two dummy variables \(X_{\mathrm{color_3}_i} = X_{\mathrm{color_4}_i}=0\). - When

coloris3 = medium dark, then \(X_{\mathrm{color_3}_i}=1\) while the other two dummy variables \(X_{\mathrm{color_2}_i} = X_{\mathrm{color_4}_i}=0\). - When

coloris4 = dark, then \(X_{\mathrm{color_4}_i}=1\) while the other two dummy variables \(X_{\mathrm{color_2}_i} = X_{\mathrm{color_3}_i}=0\).

Note that the level 1 = medium light is depicted as the baseline here. Hence, the interpretation of the coefficients in the model for each dummy variable will be compared to this baseline.

Now, let us fit this second Poisson regression model and print the model summary including coefficient estimates, standard errors, Wald’s test statistic (\(z\)-test), the corresponding \(p\)-value, and 95% confidence intervals.

# Fit the Poisson model

poisson_model2 <- glm(satell ~ width + color, family = poisson, data = train_set)

# Summarise the model output

summary_df <- tidy(poisson_model2, conf.int = TRUE) %>% mutate_if(is.numeric, round, 3)

# Display the output in table

kable(summary_df, "pipe")# Fit the Poisson regression model

poisson_model2 = glm(formula='satell ~ width + color', data=train_set, family=sm.families.Poisson()).fit()

# Extract the summary table

summary_df = poisson_model2.summary2().tables[1]

# Display the table

print(summary_df.round(3))| term | estimate | std.error | statistic | p.value | conf.low | conf.high |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | -2.915 | 0.687 | -4.244 | 0.000 | -4.257 | -1.564 |

| width | 0.161 | 0.025 | 6.495 | 0.000 | 0.112 | 0.209 |

| color2 | -0.224 | 0.180 | -1.244 | 0.213 | -0.562 | 0.145 |

| color3 | -0.458 | 0.212 | -2.160 | 0.031 | -0.867 | -0.034 |

| color4 | -0.410 | 0.231 | -1.773 | 0.076 | -0.862 | 0.047 |

Coef. Std.Err. z P>|z| [0.025 0.975]

Intercept -2.915 0.687 -4.244 0.000 -4.261 -1.568

color[T.2] -0.224 0.180 -1.244 0.213 -0.576 0.129

color[T.3] -0.458 0.212 -2.160 0.031 -0.873 -0.042

color[T.4] -0.410 0.231 -1.773 0.076 -0.862 0.043

width 0.161 0.025 6.495 0.000 0.112 0.209We can see that width and color3 are significant according to the \(p\)-value column under the significance level \(\alpha=0.05\).

10.9.1 Interpreting the results of a continuous variable

First, let us focus on the coefficient corresponding to width, while keeping color constant. Consider an observation with a given shell width \(X_{\mathrm{width}}=\texttt{w}\) cm, and another observation with a given \(X_{\mathrm{width+1}}=\texttt{w}+1\) cm (i.e., an increase of \(1\) cm). Denote the corresponding expected satell sizes as \(\lambda_{\mathrm{width}}\) and \(\lambda_{\mathrm{width+1}}\) respectively. Then we have their corresponding regression equations:

\[ \begin{align} \log \left( \lambda_{\mathrm{width}} \right) &= \beta_0 + \beta_1 \overbrace{\texttt{w}}^{X_{\mathrm{width}}} + \overbrace{\beta_2 X_{\mathrm{color_2}} + \beta_3 X_{\mathrm{color_3}} + \beta_4 X_{\mathrm{color_4}}}^{\mathrm{Constant}} \\ \log \left( \lambda_{\mathrm{width + 1}} \right) &= \beta_0 + \beta_1 \underbrace{(\texttt{w} + 1)}_{X_{\mathrm{width + 1}}} + \underbrace{\beta_2 X_{\mathrm{color_2}} + \beta_3 X_{\mathrm{color_3}} + \beta_4 X_{\mathrm{color_4}}}_{\mathrm{Constant}}. \end{align} \]

We take the difference between both equations as: \[ \begin{align} \log \left( \lambda_{\mathrm{width + 1}} \right) - \log \left( \lambda_{\mathrm{width}} \right) &= \beta_1 (\texttt{w} + 1) - \beta_1 \texttt{w} \\ &= \beta_1. \end{align} \]

We apply the logarithm property for a ratio: \[ \begin{align*} \log \left( \frac{\lambda_{\mathrm{width + 1}} }{\lambda_{\mathrm{width}}} \right) &= \log \left( \lambda_{\mathrm{width + 1}} \right) - \log \left( \lambda_{\mathrm{width}} \right) \\ &= \beta_1. \end{align*} \]

Finally, we have to exponentiate the previous equation: \[\frac{\lambda_{\mathrm{width+1}}}{\lambda_{\mathrm{width}}} = e^{\beta_1},\] which indicates that the satellite size varies in a multiplicative way when 1 cm is increased in satellite width.

Therefore, by using the estimate \(\hat{\beta_1}\) (note the hat notation) coming from the model poisson_model2, we calculate this multiplicative effect as follows (via exponentiate = TRUE in tidy()):

summary_exp_df <- tidy(poisson_model2, exponentiate = TRUE, conf.int = TRUE)

%>% mutate_if(is.numeric, round, 3)

knitr::kable(summary_exp_df, "pipe")summary_exp_df = summary_df.copy()

summary_exp_df['Coef.'] = np.exp(summary_df['Coef.'])

summary_exp_df['[0.025'] = np.exp(summary_df['[0.025'])

summary_exp_df['0.975]'] = np.exp(summary_df['0.975]'])

summary_exp_df = summary_exp_df.round(3)

print(summary_exp_df)| term | estimate | std.error | statistic | p.value | conf.low | conf.high |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.054 | 0.687 | -4.244 | 0.000 | 0.014 | 0.209 |

| width | 1.174 | 0.025 | 6.495 | 0.000 | 1.118 | 1.232 |

| color2 | 0.800 | 0.180 | -1.244 | 0.213 | 0.570 | 1.156 |

| color3 | 0.633 | 0.212 | -2.160 | 0.031 | 0.420 | 0.967 |

| color4 | 0.664 | 0.231 | -1.773 | 0.076 | 0.422 | 1.048 |

Coef. Std.Err. z P>|z| [0.025 0.975]

Intercept 0.054 0.687 -4.244 0.000 0.014 0.208

color[T.2] 0.800 0.180 -1.244 0.213 0.562 1.137

color[T.3] 0.633 0.212 -2.160 0.031 0.418 0.958

color[T.4] 0.664 0.231 -1.773 0.076 0.422 1.044

width 1.174 0.025 6.495 0.000 1.119 1.232\(\frac{\hat{\lambda}_{\mathrm{width + 1}} }{\hat{\lambda}_{\mathrm{width}}} = e^{\hat{\beta}_1} = 1.174\) indicates that the averaged satellite size (satell) of male horseshoe crabs around a female breeding nest increases by \(17.4\%\) when increasing the crab width by \(1\) cm, while keeping color constant. The interpretation of the significant coefficients corresponding to difference between the color groups and the baseline level.

10.9.2 Interpreting the results of a categorical variable

Consider two observations, one with color 1 = medium light of the prosoma (the baseline) and another with 4 = dark. Their corresponding responses are denoted as \(\lambda_{\mathrm{D}}\) (for dark) and \(\lambda_{\mathrm{L}}\) (for medium light). While holding \(X_{\mathrm{width}}\) constant, their regression equations are: \[

\begin{gather*}

\log \left( \lambda_{\mathrm{D}} \right) = \beta_0 + \overbrace{\beta_1 X_{\mathrm{width}}}^{\text{Constant}} + \beta_2 X_{\mathrm{color_2}_{\mathrm{D}}} + \beta_3 X_{\mathrm{color_3}_{\mathrm{D}}} + \beta_4 X_{\mathrm{color_4}_{\mathrm{D}}} \\

\log \left( \lambda_{\mathrm{L}} \right) = \beta_0 + \underbrace{\beta_1 X_{\mathrm{width}}}_{\text{Constant}} + \beta_2 X_{\mathrm{color_2}_{\mathrm{L}}} + \beta_3 X_{\mathrm{color_3}_{\mathrm{L}}} + \beta_4 X_{\mathrm{color_4}_{\mathrm{L}}}

\end{gather*}

\]

The corresponding color indicator variables for both \(\lambda_{\mathrm{D}}\) and \(\lambda_{\mathrm{L}}\) take on these values: \[

\begin{align*}

\log \left( \lambda_{\mathrm{D}} \right) &= \beta_0 + \overbrace{\beta_1 X_{\mathrm{width}}}^{\text{Constant}} + \beta_2 X_{\mathrm{color_2}_{\mathrm{D}}} + \beta_3 X_{\mathrm{color_3}_{\mathrm{D}}} + \beta_4 X_{\mathrm{color_4}_{\mathrm{D}}} \\

&= \beta_0 + \beta_1 X_{\mathrm{width}}+ \beta_2 \times 0 + \beta_3 \times 0 + \beta_4 \times 1 \\

&= \beta_0 + \beta_1 X_{\mathrm{width}} + \beta_4, \\

\log \left( \lambda_{\mathrm{L}} \right) &= \beta_0 + \beta_1 X_{\mathrm{width}} + \beta_2 X_{\mathrm{color_2}_{\mathrm{L}}} + \beta_3 X_{\mathrm{color_3}_{\mathrm{L}}} + \beta_4 X_{\mathrm{color_4}_{\mathrm{L}}} \\

&= \beta_0 + \beta_1 X_{\mathrm{width}}+ \beta_2 \times 0 + \beta_3 \times 0 + \beta_4 \times 0 \\

&= \beta_0 + \underbrace{\beta_1 X_{\mathrm{width}}}_{\text{Constant}}.

\end{align*}

\]

Therefore, what is the association of the level medium light with respect to dark? Let us take the differences again: \[

\begin{align*}

\log \left( \frac{\lambda_{\mathrm{D}} }{\lambda_{\mathrm{L}}} \right) &= \log \left( \lambda_{\mathrm{D}} \right) - \log \left( \lambda_{\mathrm{L}} \right) \\

&= \beta_4.

\end{align*}

\]

Then, we exponentiate the previous equation:

\[ \frac{\lambda_{\mathrm{D}} }{\lambda_{\mathrm{L}}} = e^{\beta_4}. \]

The expression \(\frac{\lambda_{\mathrm{D}} }{\lambda_{\mathrm{L}}} = e^{\beta_4}\) indicates that the response varies in a multiplicative way when the color of the prosoma changes from medium light to dark.

\(\frac{\hat{\lambda}_{\mathrm{D}} }{\hat{\lambda}_{\mathrm{L}}} = e^{\hat{\beta}_4} = 0.66\) indicates that the mean satellite size (satell) of male horseshoe crabs around a female breeding nest decreases by \(34\%\) when the color of the prosoma changes from medium light to dark, while keeping the carapace width constant.

10.9.3 Prediction using test data

Let us now predict on the test set. Besides the residual deviance discussed in Goodness of fit, the model performance can also be measured by Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence, which is defined as \[ D_{\mathrm{KL}}(\hat{y_i} \Vert \hat{\lambda}_i) = y_i \log\left(\frac{\hat{y_i}}{\hat{\lambda}_i} \right) - y_i + \hat{\lambda}_i. \] Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence is a measure of how one probability distribution diverges from a reference distribution. In the context of Poisson regression, KL divergence quantifies how much the predicted Poisson distribution diverges from the true observed data.

Averaging \(\overline{D}_{\mathrm{KL}}(\hat{y}\Vert \hat{\lambda}) = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n D_{\mathrm{KL}}(\hat{y_i} \Vert \hat{\lambda}_i)\) across all observations gives a measure of how well the model captures the true data distribution. Smaller averaged KL values indicate better fit.

# Factorize `color` in test set

test_set['color'] = test_set['color'].astype('category')

# Predict

predictions = poisson_model2.predict(test_set)

actuals = test_set['satell']

# KL divergence

kf = 1

print(f"KF divergence: {kf:.4f}")KL divergence: 1 KL divergence: 1.0000Poisson residual deviance equals 2 times the KL divergence of Poisson distribution summed across all points. It measures the difference in log-likelihood between a saturated model (perfect fit) and the fitted model as defined in Goodness of fit. Lower deviance values indicate the model predictions are closer to the observed data.

10.10 Storytelling

The data case explores the relationship between satellite size, i.e., the number of male horseshoe crabs around the female horseshoe breeding nests, and several phenotypic characteristis of the female horseshoe crabs. The graphical display suggests that there is a dependence between satellite sizes and female horseshoe crab widths. The Poisson regression modelling suggests that widths is significantely related to satellite size and the dark color is significantly different to the medium light color of the female horseshoe size, given constant confoudning variables at the 5% significance level.

10.11 Practice Problems

In this final section, you can test your understanding with the following conceptual interactive exercises, and then proceed to work through an inferential analysis of a simple dataset.

10.11.1 Conceptual Questions

- What makes Poisson regression appropriate for modelling the number of satellites per crab?

Click to reveal answer

The response variable (number of satellites) is a non-negative integer, shows right skewness, and represents event counts for a fixed unit (one crab), all of which make Poisson regression appropriate.- What is the key assumption made about the distribution of the response by a classical Poisson regression model?

Click to reveal answer

Equidispersion: The conditional distribution of the response given the covariates follows a Poisson distribution with mean equal to variance.- Why do we use the log function in Poisson regression?

Click to reveal answer

The log function (technically the log link) ensures that the predicted mean of the response variable is always positive, which is necessary since counts cannot be negative.- In the univariate model, what does a positive coefficient on carapace width mean?

Click to reveal answer

Larger female crabs are expected to attract more satellite males, holding all other variables constant.- What can the incidence rate ratio (IRR) tell us in the context of carapace width for this dataset?

Click to reveal answer

The IRR indicates the multiplicative change in the expected number of satellites for each one-unit increase in carapace width, holding other variables constant.- In this chapter, why did we use binning (with grouped means) before fitting to a Poisson model?

Click to reveal answer

Binning helps to visualize the relationship between carapace width and satellite size, by highlighting trends in the mean response of the data, to assess whether a log-linear trend is plausible.- What does residual deviance measure in a Poisson regression model?

Click to reveal answer

How far the fitted model is from the saturated model (perfect fit) – lower values indicate a better fit.- How do we assess the goodness-of-fit of a Poisson regression model?

Click to reveal answer

Use the residual deviance, and its associated p-value from a chi-squared test to assess goodness-of-fit: A high p-value indicates a good fit, while a low p-value indicates a lack-of-fit.- What does overdispersion mean? Why is it a problem for Poisson regression?

Click to reveal answer

Overdispersion occurs when the variance of the response variable exceeds its mean. This violates the equidispersion assumption, which can lead to underestimated standard errors and overstated significance of predictors.- How can we diagnoze overdispersion in the horseshoe crab dataset?

Click to reveal answer

We can compare the residual deviance to the degrees of freedom. If the ratio is significantly greater than 1, this indicates overdispersion.- Why are categorical predictors, such as color, included as indicator variables in Poisson regression?

Click to reveal answer

They allow the model to estimate separate effects for each category relative to a baseline category, which allows for the analysis of how different levels of the categorical variable influence the response.- Why do we interpret on the response scale (exponentiated coefficients) rather than the log scale in Poisson regression?

Click to reveal answer

This is simply more intuitive, as it tells us the multiplicative effect on the expected count of the response variable for a one-unit change in the predictor.- How do we interpret the coefficient for a categorical variable in Poisson regression?

Click to reveal answer

The coefficient (exponentiated!) represents the change in the expected count of the response variable when moving from the baseline category to the category represented by the coefficient (holding other variables constant).10.11.2 Coding Question

Problem 1

In this problem, you are given a set of 700 individuals with different demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, along with their reported number of annual doctor visits. Your task will be to perform a full poisson regression analysis following a similar structure to this chapter. The variables involved are:

| Variable Name | Description |

|---|---|

| doctor_visits | The number of visits in the past year (0-20+) |

| age | Age in years |

| income | Annual income in USD |

| education_years | Total years of education |

| married | Married or not (0 or 1) |

| urban | Urban residence or not (0 or 1) |

| insurance | Health insurance or not (0 or 1) |

By the end of these questions, you will be able to describe how age, insurance and socioeconomic factors affect the number of doctor visits individuals need. You will determine whether the Poisson model is appropriate, and which predictors matter most in answering this problem.

A. Data Wrangling and Exploratory Data Analysis

Let us check if doctor_visists meets the assumptions for a classical Poisson model:

Check if it is a non-negative integer.

Examine its distribution, computing the mean and variance.

Is equidispersion (Var \(\approx\) Mean) plausible here?

Click to reveal answer

── Attaching core tidyverse packages ──────────────────────── tidyverse 2.0.0 ──

✔ forcats 1.0.1 ✔ purrr 1.1.0

✔ lubridate 1.9.4 ✔ stringr 1.5.2

── Conflicts ────────────────────────────────────────── tidyverse_conflicts() ──

✖ broom::bootstrap() masks asbio::bootstrap()

✖ gridExtra::combine() masks dplyr::combine()

✖ magrittr::extract() masks tidyr::extract()

✖ dplyr::filter() masks stats::filter()

✖ dplyr::lag() masks stats::lag()

✖ lubridate::pm() masks asbio::pm()

✖ purrr::set_names() masks magrittr::set_names()

ℹ Use the conflicted package (<http://conflicted.r-lib.org/>) to force all conflicts to become errors

Attaching package: 'MASS'

The following object is masked _by_ '.GlobalEnv':

crabs

The following object is masked from 'package:dplyr':

select

Attaching package: 'zoo'

The following objects are masked from 'package:base':

as.Date, as.Date.numericThis is DHARMa 0.4.7. For overview type '?DHARMa'. For recent changes, type news(package = 'DHARMa')select <- dplyr::select

## setwd("/home/michael/coding/stats-textbook/regression-cookbook")

load("./data/poisson_regression.rda")

df <- poisson_regression

# Convert to categorical

df <- df %>%

mutate(

married = factor(married),

urban = factor(urban),

insurance = factor(insurance)

)

############################################################

# A. Poisson Regression Assumptions

############################################################

summary(df$doctor_visits) Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

0.00 3.00 5.00 5.13 7.00 21.00 mean_val <- mean(df$doctor_visits)

var_val <- var(df$doctor_visits)

c(mean = mean_val, variance = var_val) mean variance

5.130000 9.624725 table(df$doctor_visits)

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 20 21

18 59 108 155 140 151 93 84 62 43 28 23 11 10 1 3 5 3 2 1 cat("Mean =", mean_val, "Variance =", var_val, "\n")Mean = 5.13 Variance = 9.624725 ############################################################

# Imports

############################################################

import pyreadr

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

import statsmodels.api as sm

import statsmodels.formula.api as smf

from scipy.stats import chi2

sns.set(style="whitegrid")

############################################################

# Load data (RDA)

############################################################

result = pyreadr.read_r("./data/poisson_regression.rda")

df = result["poisson_regression"]

# Convert categorical variables

for col in ["married", "urban", "insurance"]:

df[col] = df[col].astype("category")

############################################################

# A. Poisson Regression Assumptions

############################################################

print(df["doctor_visits"].describe())count 1000.000000

mean 5.130000

std 3.102374

min 0.000000

25% 3.000000

50% 5.000000

75% 7.000000

max 21.000000

Name: doctor_visits, dtype: float64mean_val = df["doctor_visits"].mean()

var_val = df["doctor_visits"].var()

print({"mean": mean_val, "variance": var_val}){'mean': np.float64(5.13), 'variance': np.float64(9.624724724724727)}print(df["doctor_visits"].value_counts().sort_index())doctor_visits

0.0 18

1.0 59

2.0 108

3.0 155

4.0 140

5.0 151

6.0 93

7.0 84

8.0 62

9.0 43

10.0 28

11.0 23

12.0 11

13.0 10

14.0 1

15.0 3

16.0 5

17.0 3

20.0 2

21.0 1

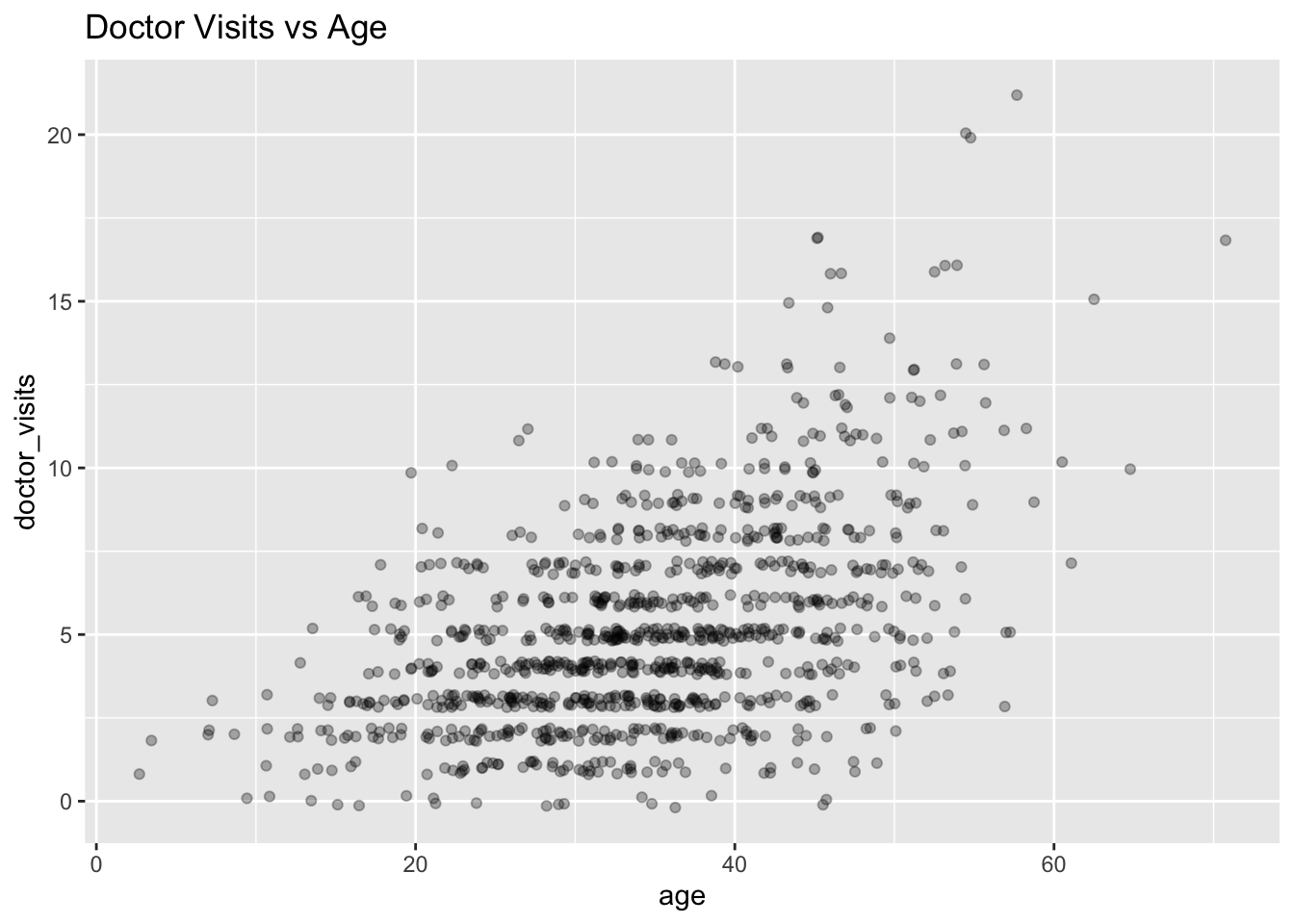

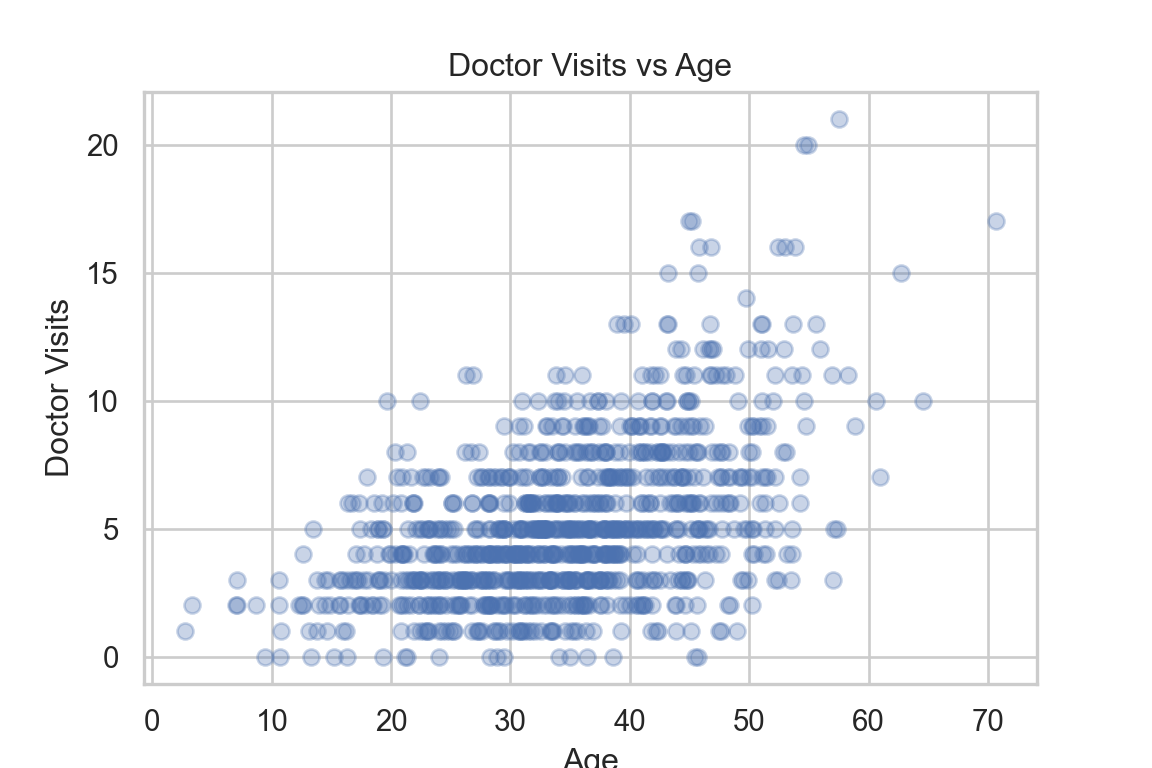

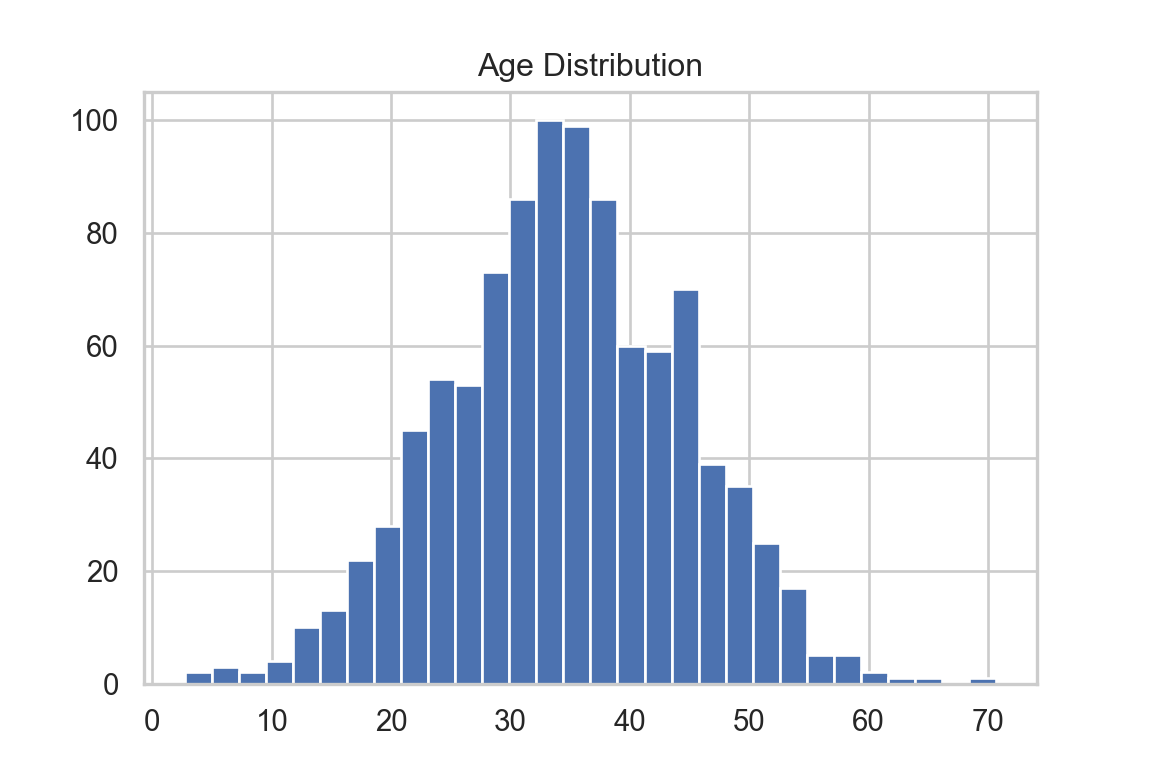

Name: count, dtype: int64B. A Graphical Look

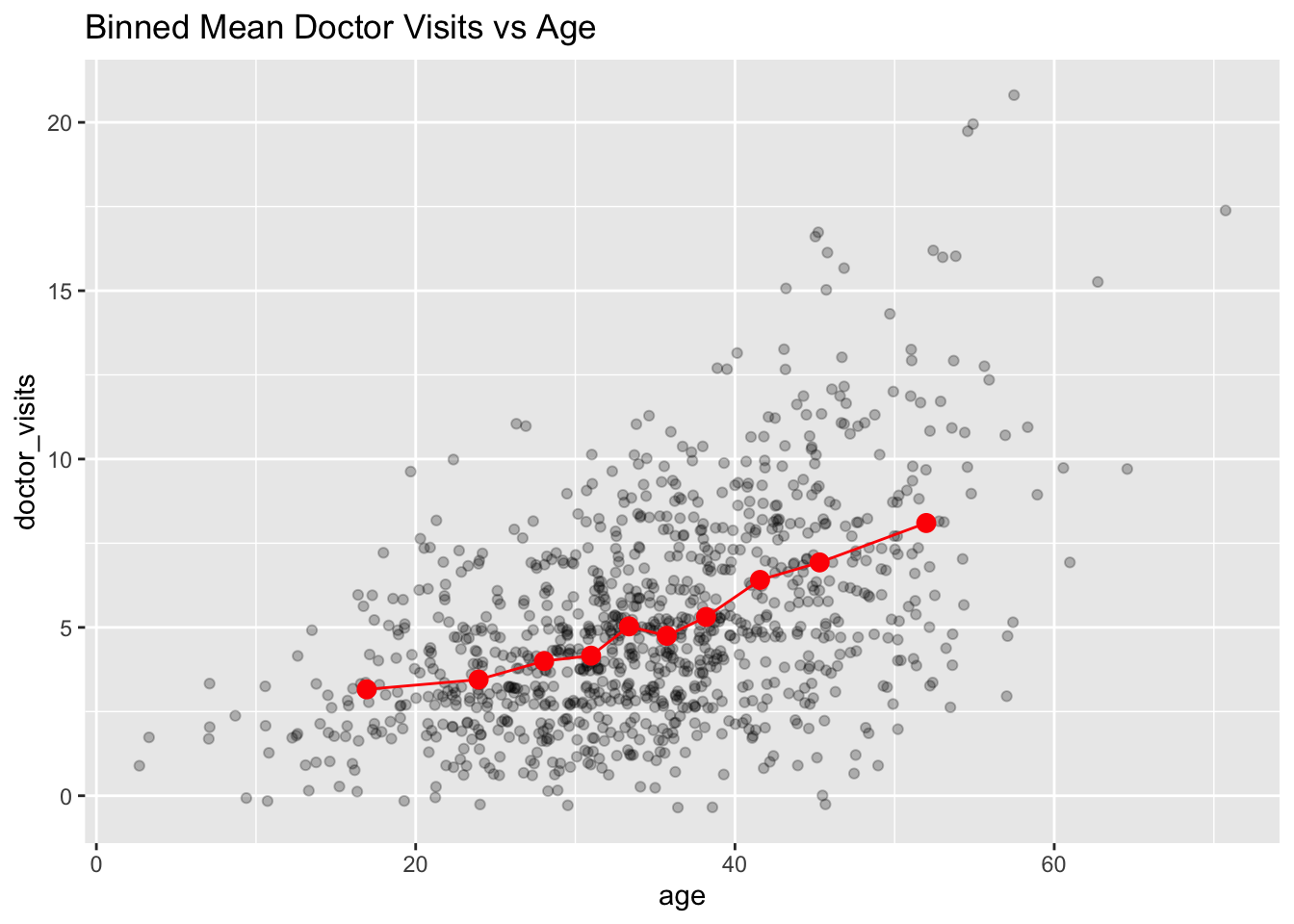

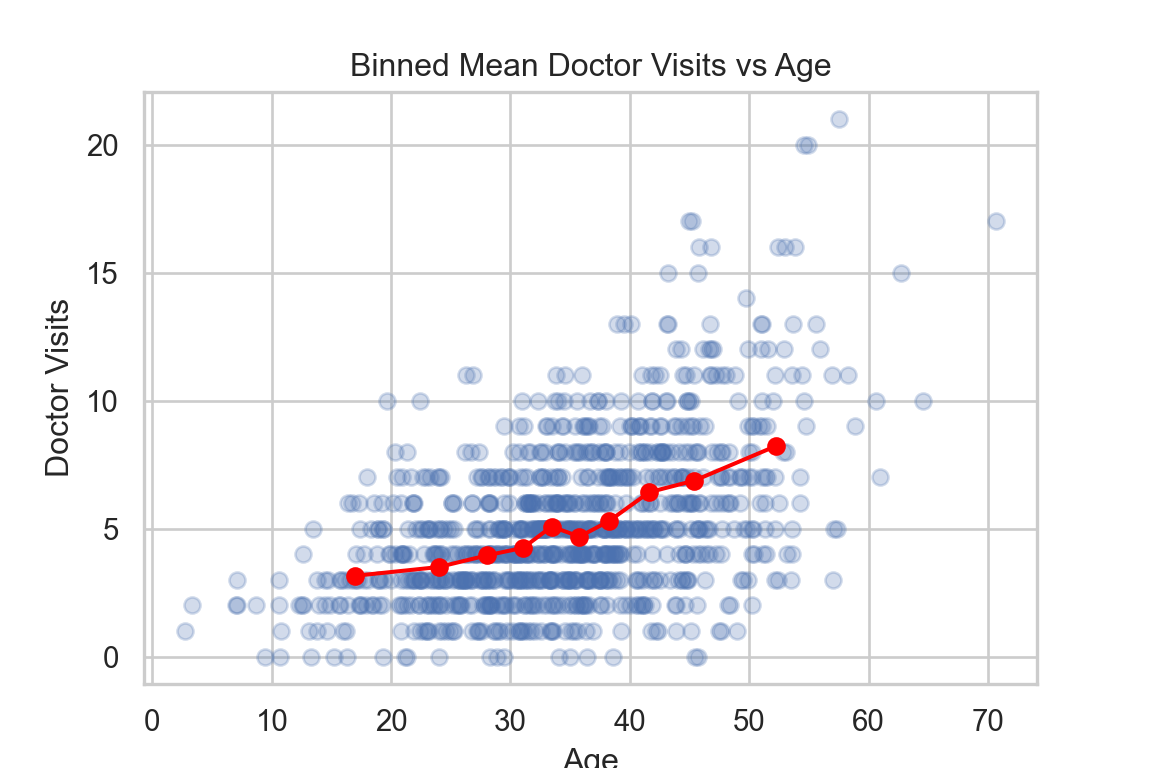

Create a scatterplot of

doctor_visitsvsage, adding an offset to the points with jitter for visibility.Comment on the (1) skewness, (2) heteroskedasticity and (3) whether the variability increases with the mean, relating this to your observation in question A3.

Click to reveal answer

############################################################

# B. A Graphical Look

############################################################

# Jitter scatter with marginal histograms

p_scatter <- ggplot(df, aes(x = age, y = doctor_visits)) +

geom_jitter(alpha = 0.3, width = 0.2, height = 0.2) +

labs(title = "Doctor Visits vs Age")

p_hist_x <- ggplot(df, aes(x = age)) + geom_histogram(bins = 30)

p_hist_y <- ggplot(df, aes(x = doctor_visits)) + geom_histogram(bins = 30)

print(p_scatter)

print(p_hist_x)

print(p_hist_y)

############################################################

# B. A Graphical Look

############################################################

plt.figure(figsize=(6,4))

plt.scatter(df["age"], df["doctor_visits"], alpha=0.3)

plt.xlabel("Age")

plt.ylabel("Doctor Visits")

plt.title("Doctor Visits vs Age")

plt.show()

plt.figure(figsize=(6,4))

plt.hist(df["age"], bins=30)

plt.title("Age Distribution")

plt.show()

plt.figure(figsize=(6,4))

plt.hist(df["doctor_visits"], bins=30)

plt.title("Doctor Visits Distribution")

plt.show()

The distribution of doctor_visits is right-skewed, the spread increases with age, and the variability appears larger at higher mean values. This is consistent with the Poisson mean–variance relationship noted in A3.

C. Data Wrangling

Now, prepare the data for modelling:

Convert all appropriate variables to factors. Report the number of levels in each factor to verify this is working.

Drop any missing observations.

Produce a summary table of all variables.

Click to reveal answer

############################################################

# C. Data Wrangling

############################################################

summary(df) age income education_years urban married insurance

Min. : 2.70 Min. :-7021 Min. :10.00 0:293 0:498 0:422

1st Qu.:28.18 1st Qu.:40416 1st Qu.:12.00 1:707 1:502 1:578

Median :34.60 Median :50727 Median :15.00

Mean :34.60 Mean :50126 Mean :15.07

3rd Qu.:41.70 3rd Qu.:59808 3rd Qu.:18.00

Max. :70.70 Max. :92761 Max. :20.00

doctor_visits

Min. : 0.00

1st Qu.: 3.00

Median : 5.00

Mean : 5.13

3rd Qu.: 7.00

Max. :21.00 $married

0 1

498 502

$urban

0 1

293 707

$insurance

0 1

422 578 ############################################################

# C. Data Wrangling

############################################################

print(df.describe(include="all")) age income ... insurance doctor_visits

count 1000.000000 1000.000000 ... 1000.0 1000.000000

unique NaN NaN ... 2.0 NaN

top NaN NaN ... 1.0 NaN

freq NaN NaN ... 578.0 NaN

mean 34.604300 50125.837370 ... NaN 5.130000

std 10.013233 14377.333877 ... NaN 3.102374

min 2.700000 -7020.670000 ... NaN 0.000000

25% 28.175000 40416.130000 ... NaN 3.000000

50% 34.600000 50726.830000 ... NaN 5.000000

75% 41.700000 59808.250000 ... NaN 7.000000

max 70.700000 92760.620000 ... NaN 21.000000

[11 rows x 7 columns]for col in ["married", "urban", "insurance"]:

print(f"\n{col} counts:")

print(df[col].value_counts())

married counts:

married

1.0 502

0.0 498

Name: count, dtype: int64

urban counts:

urban

1.0 707

0.0 293

Name: count, dtype: int64

insurance counts:

insurance

1.0 578

0.0 422

Name: count, dtype: int64The variables married, urban, and insurance are categorical with a small number of discrete levels, and can thus be treated as factors.

D. Exploratory Data Analysis

Following the horsehsoe crab example closely:

Bin

ageinto 10 equally-sized groups, and compute the meanageanddoctor_visitsof each.Overlay the bin means on the scatterplot produced in question B1.

Comment on the trend: How does doctor visitation vary with age? Does this trend (if any) appear linear?

Click to reveal answer

############################################################

# D. Exploratory Data Analysis

############################################################

df_binned <- df %>%

mutate(age_bin = ntile(age, 10)) %>%

group_by(age_bin) %>%

summarize(

mean_age = mean(age),

mean_visits = mean(doctor_visits),

.groups = "drop"

)

ggplot(df, aes(x = age, y = doctor_visits)) +

geom_jitter(alpha = 0.25) +

geom_point(data = df_binned, aes(x = mean_age, y = mean_visits),

color = "red", size = 3) +

geom_line(data = df_binned, aes(x = mean_age, y = mean_visits),

color = "red") +

labs(title = "Binned Mean Doctor Visits vs Age")

############################################################

# D. Exploratory Data Analysis (Binning)

############################################################

df["age_bin"] = pd.qcut(df["age"], 10, labels=False)

df_binned = (

df.groupby("age_bin")

.agg(mean_age=("age", "mean"),

mean_visits=("doctor_visits", "mean"))

.reset_index()

)

plt.figure(figsize=(6,4))

plt.scatter(df["age"], df["doctor_visits"], alpha=0.25)

plt.plot(df_binned["mean_age"], df_binned["mean_visits"],

color="red", marker="o")

plt.title("Binned Mean Doctor Visits vs Age")

plt.xlabel("Age")

plt.ylabel("Doctor Visits")

plt.show()

The number of doctor visits tend to increase with age on average—the binned means show a smooth upward trend that is not strictly linear on the response scale.

E. Simple Data Modelling & Estimation

We will model the expected number of visits of some individual \(i\) as \(\log(\lambda_i) = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X_{i,\text{age}}\).

Fit the univariate Poisson regression above.

Print a coefficient table.

Compute and display \(\text{IRR}(\text{exp}(\beta_1))\).

Compute and display the 95% confidence interval for \(\beta_1\).

Click to reveal answer

############################################################

# E. Simple Data Modelling & Estimation

############################################################

mod_uni <- glm(doctor_visits ~ age, family = poisson(), data = df)

summary(mod_uni)

Call:

glm(formula = doctor_visits ~ age, family = poisson(), data = df)

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

(Intercept) 0.545217 0.054529 9.999 <2e-16 ***

age 0.030181 0.001401 21.537 <2e-16 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

(Dispersion parameter for poisson family taken to be 1)

Null deviance: 1822.8 on 999 degrees of freedom

Residual deviance: 1357.5 on 998 degrees of freedom

AIC: 4662.7

Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 4tidy(mod_uni, conf.int = TRUE) %>%

mutate(IRR = exp(estimate),

IRR_low = exp(conf.low),

IRR_high = exp(conf.high))# A tibble: 2 × 10

term estimate std.error statistic p.value conf.low conf.high IRR IRR_low

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 (Inte… 0.545 0.0545 10.00 1.54e- 23 0.438 0.652 1.72 1.55

2 age 0.0302 0.00140 21.5 7.04e-103 0.0274 0.0329 1.03 1.03

# ℹ 1 more variable: IRR_high <dbl>############################################################

# E. Simple Poisson Regression

############################################################

mod_uni = smf.glm(

"doctor_visits ~ age",

data=df,

family=sm.families.Poisson()

).fit()

print(mod_uni.summary()) Generalized Linear Model Regression Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: doctor_visits No. Observations: 1000

Model: GLM Df Residuals: 998

Model Family: Poisson Df Model: 1

Link Function: Log Scale: 1.0000

Method: IRLS Log-Likelihood: -2329.3

Date: Wed, 18 Feb 2026 Deviance: 1357.5

Time: 22:23:42 Pearson chi2: 1.30e+03

No. Iterations: 4 Pseudo R-squ. (CS): 0.3720

Covariance Type: nonrobust

==============================================================================

coef std err z P>|z| [0.025 0.975]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Intercept 0.5452 0.055 9.999 0.000 0.438 0.652

age 0.0302 0.001 21.536 0.000 0.027 0.033

==============================================================================# IRRs + confidence intervals

uni_params = mod_uni.params

uni_ci = mod_uni.conf_int()

uni_results = pd.DataFrame({

"estimate": uni_params,

"conf_low": uni_ci[0],

"conf_high": uni_ci[1],

"IRR": np.exp(uni_params),

"IRR_low": np.exp(uni_ci[0]),

"IRR_high": np.exp(uni_ci[1])

})

print(uni_results) estimate conf_low conf_high IRR IRR_low IRR_high

Intercept 0.545217 0.438340 0.652093 1.724982 1.550132 1.919554

age 0.030181 0.027435 0.032928 1.030641 1.027814 1.033476The IRR is the multiplicative change in the expected number of doctor visits associated with a one-year increase in age. The 95% confidence interval for \(\beta_1\) does not include zero, indicating a statistically significant association between age and doctor visits.

F. Goodness of Fit

Using your univariate model from question E:

Report the residual deviance and the degrees of freedom.

Compute a chi-square goodness-of-fit test.

Compute the Pearson dispersion statistic.

Is this an overdispersion or underdispersion, and how do you know?

Click to reveal answer

############################################################

# F. Goodness of Fit

############################################################

res_dev <- deviance(mod_uni)

df_res <- df.residual(mod_uni)

gof_pval <- 1 - pchisq(res_dev, df_res)

pearson_X2 <- sum(residuals(mod_uni, type = "pearson")^2)

dispersion <- pearson_X2 / df_res

cat("Residual deviance =", res_dev, "df =", df_res, "GOF p-value =", gof_pval, "\n")Residual deviance = 1357.524 df = 998 GOF p-value = 1.957323e-13 cat("Pearson X2 =", pearson_X2, "Dispersion =", dispersion, "\n")Pearson X2 = 1299.367 Dispersion = 1.301971 ############################################################

# F. Goodness of Fit

############################################################

res_dev = mod_uni.deviance

df_res = mod_uni.df_resid

gof_pval = 1 - chi2.cdf(res_dev, df_res)

pearson_X2 = np.sum(mod_uni.resid_pearson**2)

dispersion = pearson_X2 / df_res

print(f"Residual deviance = {res_dev:.3f}")Residual deviance = 1357.524print(f"df = {df_res}")df = 998print(f"GOF p-value = {gof_pval:.4f}")GOF p-value = 0.0000print(f"Pearson X2 = {pearson_X2:.3f}")Pearson X2 = 1299.367print(f"Dispersion = {dispersion:.3f}")Dispersion = 1.302The dispersion statistic is greater than 1, indicating mild overdispersion relative to the Poisson assumption.

G. Inference

Perform the Wald test for \(\beta_1\).

Determine the 95% confidence interval for the IRR computed in question E3.

-

Explain how the estimated coefficient \(\hat{\beta}_1\) affects the relationship between age and the expected number of doctor visits. In particular:

Describe how the expected number of doctor visits changes as age increases.

Is the relationship linear, exponential, or something else? Explain your reasoning.

Do equal increases in age lead to multiplicative or additive changes in the expected number of visits? Why?

Click to reveal answer

############################################################

# G. Inference

############################################################

coef_uni <- tidy(mod_uni, conf.int = TRUE)

coef_uni# A tibble: 2 × 7

term estimate std.error statistic p.value conf.low conf.high

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 (Intercept) 0.545 0.0545 10.00 1.54e- 23 0.438 0.652

2 age 0.0302 0.00140 21.5 7.04e-103 0.0274 0.0329IRR for age = 1.030641 The estimated coefficient \(\hat{\beta}_1\) is included in the model through the log link function, \[ \log(\lambda_i) = \beta_0 + \beta_1 \,\text{age}_i. \] This implies that the expected number of doctor visits satisfies \[ \lambda_i = \exp(\beta_0)\exp(\beta_1 \,\text{age}_i). \]

As age increases, the expected number of doctor visits increases multiplicatively rather than additively: Each one-year increase in age multiplies the expected number of visits by a constant factor equal to the incidence rate ratio (IRR), i.e. \(\exp(\hat{\beta}_1)\).

Therefore, the relationship between age and expected doctor visits is exponential in the response scale and linear in the log scale. Equal increases in age produce proportionally equal changes in the expected count (a feature of all Poisson regression models).

############################################################

# G. Inference

############################################################

print("IRR for age =", np.exp(mod_uni.params["age"]))IRR for age = 1.0306414682533183The estimated coefficient \(\hat{\beta}_1\) is included in the model through the log link function, \[ \log(\lambda_i) = \beta_0 + \beta_1 \,\text{age}_i. \] This implies that the expected number of doctor visits satisfies \[ \lambda_i = \exp(\beta_0)\exp(\beta_1 \,\text{age}_i). \]

As age increases, the expected number of doctor visits increases multiplicatively rather than additively: Each one-year increase in age multiplies the expected number of visits by a constant factor equal to the incidence rate ratio (IRR), i.e. \(\exp(\hat{\beta}_1)\).

Therefore, the relationship between age and expected doctor visits is exponential in the response scale and linear in the log scale. Equal increases in age produce proportionally equal changes in the expected count (a feature of all Poisson regression models).

H. Multivariate Poisson Regression

Now, extend the model to: \[\log(\lambda_i) = \beta_0 + \sum_{j}\beta_i X_{i,j},\] where \(j\) runs over age, income, education_years, married, urban, and insurance.

Fit the multivariable model above.

Compute the IRRs and 95% confidence intervals.

Interpret the effect of insurance (insured or not).

Which predictors are the most significant? How do you know?

Fit another model with

age * insurance, and perform a likelihood-ratio test vs the additive model above.Based on the result, does insurance modify the effect of age?

Click to reveal answer

############################################################

# H. Multivariate Poisson Regression

############################################################

form_multi <- doctor_visits ~ age + income + education_years +

married + urban + insurance

mod_multi <- glm(form_multi, family = poisson(), data = df)

summary(mod_multi)

Call:

glm(formula = form_multi, family = poisson(), data = df)

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

(Intercept) 1.710e-02 1.073e-01 0.159 0.873

age 2.913e-02 1.396e-03 20.863 < 2e-16 ***

income -1.165e-05 9.493e-07 -12.276 < 2e-16 ***

education_years 5.647e-02 4.571e-03 12.353 < 2e-16 ***

married1 1.229e-01 2.814e-02 4.369 1.25e-05 ***

urban1 1.742e-01 3.181e-02 5.474 4.40e-08 ***

insurance1 1.359e-01 2.872e-02 4.730 2.24e-06 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

(Dispersion parameter for poisson family taken to be 1)

Null deviance: 1822.8 on 999 degrees of freedom

Residual deviance: 1002.2 on 993 degrees of freedom

AIC: 4317.3

Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 4tidy(mod_multi, conf.int = TRUE) %>%

mutate(IRR = exp(estimate),

IRR_low = exp(conf.low),

IRR_high = exp(conf.high))# A tibble: 7 × 10

term estimate std.error statistic p.value conf.low conf.high IRR IRR_low

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 (Inter… 1.71e-2 1.07e-1 0.159 8.73e- 1 -1.94e-1 2.27e-1 1.02 0.824

2 age 2.91e-2 1.40e-3 20.9 1.15e-96 2.64e-2 3.19e-2 1.03 1.03

3 income -1.17e-5 9.49e-7 -12.3 1.22e-34 -1.35e-5 -9.79e-6 1.000 1.000

4 educat… 5.65e-2 4.57e-3 12.4 4.67e-35 4.75e-2 6.54e-2 1.06 1.05

5 marrie… 1.23e-1 2.81e-2 4.37 1.25e- 5 6.78e-2 1.78e-1 1.13 1.07

6 urban1 1.74e-1 3.18e-2 5.47 4.40e- 8 1.12e-1 2.37e-1 1.19 1.12

7 insura… 1.36e-1 2.87e-2 4.73 2.24e- 6 7.97e-2 1.92e-1 1.15 1.08

# ℹ 1 more variable: IRR_high <dbl># Interaction: age * insurance

mod_int <- glm(doctor_visits ~ age * insurance + income + education_years +

married + urban, family = poisson(), data = df)

anova(mod_multi, mod_int, test = "Chisq")Analysis of Deviance Table

Model 1: doctor_visits ~ age + income + education_years + married + urban +

insurance

Model 2: doctor_visits ~ age * insurance + income + education_years +

married + urban

Resid. Df Resid. Dev Df Deviance Pr(>Chi)

1 993 1002.2

2 992 1001.8 1 0.43642 0.5089############################################################

# H. Multivariate Poisson Regression

############################################################

formula_multi = (

"doctor_visits ~ age + income + education_years "

"+ married + urban + insurance"

)

mod_multi = smf.glm(

formula_multi,

data=df,

family=sm.families.Poisson()

).fit()

print(mod_multi.summary()) Generalized Linear Model Regression Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: doctor_visits No. Observations: 1000

Model: GLM Df Residuals: 993

Model Family: Poisson Df Model: 6

Link Function: Log Scale: 1.0000

Method: IRLS Log-Likelihood: -2151.7

Date: Wed, 18 Feb 2026 Deviance: 1002.2

Time: 22:23:42 Pearson chi2: 940.

No. Iterations: 4 Pseudo R-squ. (CS): 0.5598

Covariance Type: nonrobust

====================================================================================

coef std err z P>|z| [0.025 0.975]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Intercept 0.0171 0.107 0.159 0.873 -0.193 0.227

married[T.1.0] 0.1229 0.028 4.369 0.000 0.068 0.178

urban[T.1.0] 0.1742 0.032 5.474 0.000 0.112 0.237

insurance[T.1.0] 0.1359 0.029 4.730 0.000 0.080 0.192

age 0.0291 0.001 20.863 0.000 0.026 0.032

income -1.165e-05 9.49e-07 -12.276 0.000 -1.35e-05 -9.79e-06

education_years 0.0565 0.005 12.353 0.000 0.048 0.065

====================================================================================multi_params = mod_multi.params

multi_ci = mod_multi.conf_int()

multi_results = pd.DataFrame({

"estimate": multi_params,

"conf_low": multi_ci[0],

"conf_high": multi_ci[1],

"IRR": np.exp(multi_params),

"IRR_low": np.exp(multi_ci[0]),

"IRR_high": np.exp(multi_ci[1])

})

print(multi_results) estimate conf_low conf_high IRR IRR_low IRR_high

Intercept 0.017104 -0.193212 0.227420 1.017251 0.824308 1.255357

married[T.1.0] 0.122949 0.067791 0.178106 1.130826 1.070142 1.194953

urban[T.1.0] 0.174160 0.111803 0.236516 1.190246 1.118293 1.266828

insurance[T.1.0] 0.135868 0.079568 0.192167 1.145530 1.082820 1.211873

age 0.029131 0.026394 0.031868 1.029559 1.026746 1.032381

income -0.000012 -0.000014 -0.000010 0.999988 0.999986 0.999990

education_years 0.056471 0.047511 0.065431 1.058096 1.048658 1.067619# Interaction model

mod_int = smf.glm(

"doctor_visits ~ age * insurance + income + education_years + married + urban",

data=df,

family=sm.families.Poisson()

).fit()

lr_stat = 2 * (mod_int.llf - mod_multi.llf)

df_diff = mod_int.df_model - mod_multi.df_model

p_lr = 1 - chi2.cdf(lr_stat, df_diff)

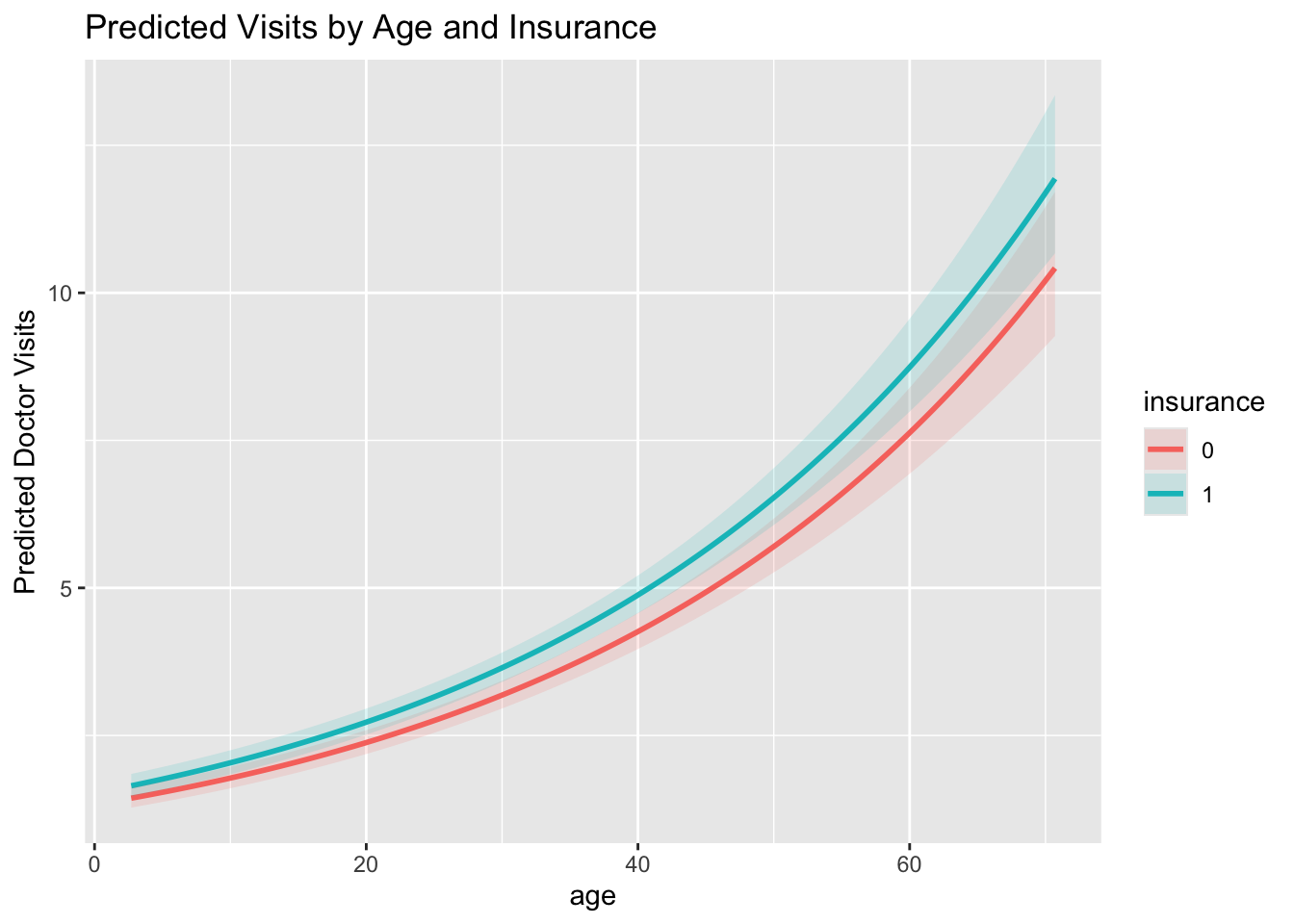

print("LR test statistic =", lr_stat)LR test statistic = 0.43641994780045934print("df =", df_diff)df = 1print("p-value =", p_lr)p-value = 0.5088554748118505Holding all other variables constant, insured individuals are expected to have about 14.6% more doctor visits than uninsured individuals (IRR ≈ 1.15). The 95% confidence interval for the IRR does not include 1, indicating this effect is statistically significant.

The most statistically significant predictors are age, education_years, married, urban, and insurance, as their confidence intervals for the IRR do not include 1. Among these, age shows the most precise and consistent effect. education_years also shows a clear positive association with doctor_visits. income has a very small effect size despite being statistically significant.

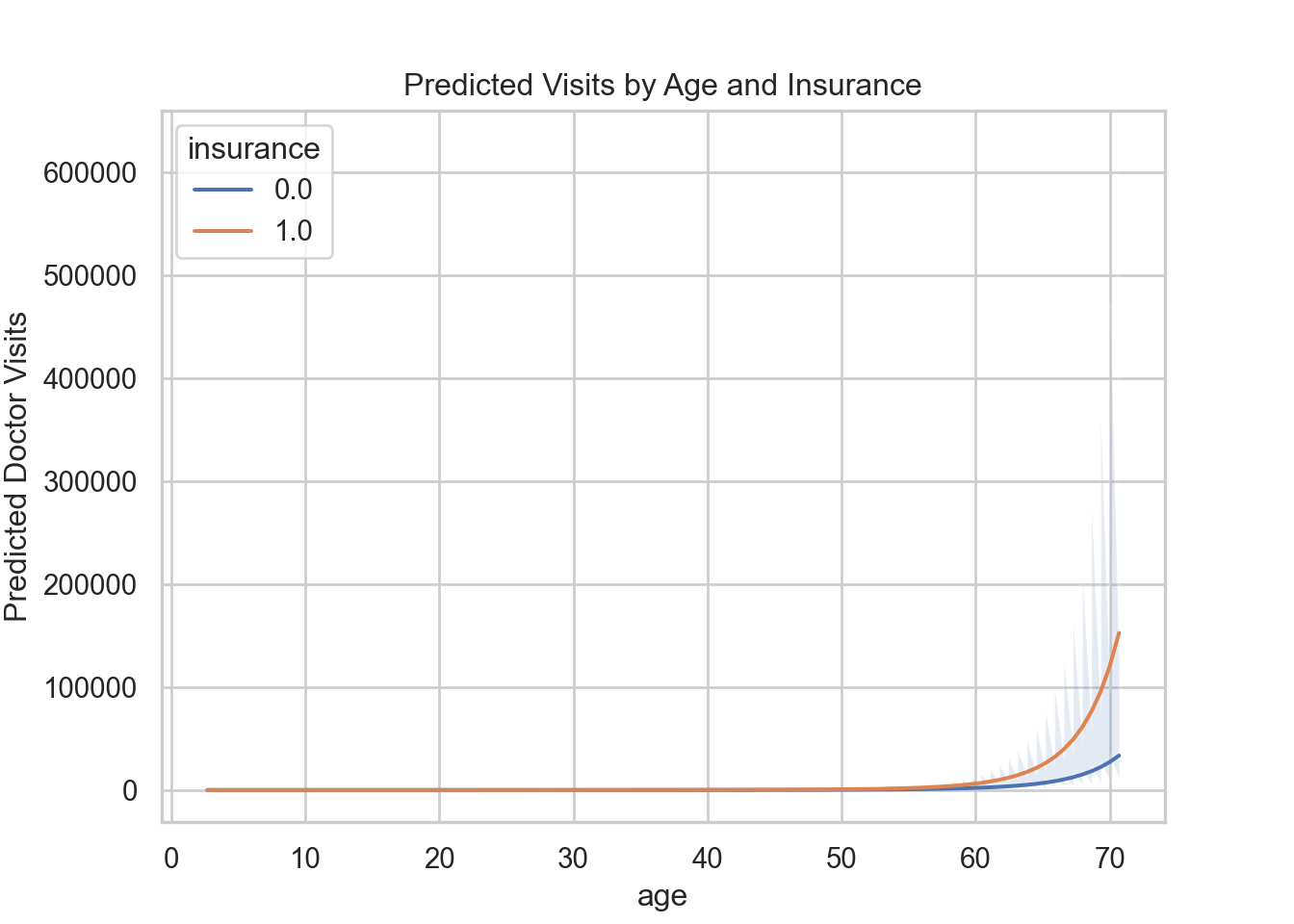

I. Prediction & KL Divergence

Using the multivariate model from question H:

Predict the expected number of doctor visits for a grid of age values, from 20 to 80.

Plot predicted visits for insured and uninsured groups, including 95% confidence interval bands.

Compute the KL divergence. How does this value reflect the model fit?

Click to reveal answer

############################################################

# I. Prediction & KL Divergence

############################################################

# Prediction grid for ages

age_grid <- seq(min(df$age), max(df$age), length.out = 100)

newdata <- expand.grid(

age = age_grid,

income = mean(df$income),

education_years = mean(df$education_years),

married = levels(df$married)[1],

urban = levels(df$urban)[1],

insurance = levels(df$insurance)

)

pred_link <- predict(mod_multi, newdata, type = "link", se.fit = TRUE)

newdata$fit <- exp(pred_link$fit)

newdata$lower95 <- exp(pred_link$fit - 1.96 * pred_link$se.fit)

newdata$upper95 <- exp(pred_link$fit + 1.96 * pred_link$se.fit)

ggplot(newdata, aes(x = age, y = fit, color = insurance)) +

geom_line(linewidth = 1) +

geom_ribbon(aes(ymin = lower95, ymax = upper95, fill = insurance),

alpha = 0.15, color = NA) +

labs(y = "Predicted Doctor Visits", title = "Predicted Visits by Age and Insurance")

# KL Divergence

lambda_hat <- fitted(mod_multi)

y <- df$doctor_visits

KL_i <- ifelse(y == 0,

-y + lambda_hat,

y * log(y / lambda_hat) - y + lambda_hat)

KL_avg <- mean(KL_i)

cat("Average KL divergence =", KL_avg, "\n")Average KL divergence = 0.5010995 ############################################################

# I. Prediction & KL Divergence

############################################################

age_grid = np.linspace(df["age"].min(), df["age"].max(), 100)

newdata = pd.DataFrame({

"age": np.repeat(age_grid, df["insurance"].cat.categories.size),

"income": df["income"].mean(),

"education_years": df["education_years"].mean(),

"married": df["married"].cat.categories[0],

"urban": df["urban"].cat.categories[0],

"insurance": np.tile(df["insurance"].cat.categories, 100)

})

# Ensure categories match

for col in ["married", "urban", "insurance"]:

newdata[col] = newdata[col].astype("category")

newdata[col] = newdata[col].cat.set_categories(df[col].cat.categories)

pred = mod_multi.get_prediction(newdata)

pred_summary = pred.summary_frame()

newdata["fit"] = np.exp(pred_summary["mean"])

newdata["lower95"] = np.exp(pred_summary["mean_ci_lower"])

newdata["upper95"] = np.exp(pred_summary["mean_ci_upper"])

plt.figure(figsize=(7,5))

sns.lineplot(data=newdata, x="age", y="fit", hue="insurance")

plt.fill_between(

newdata["age"],

newdata["lower95"],

newdata["upper95"],

alpha=0.15

)

plt.ylabel("Predicted Doctor Visits")

plt.title("Predicted Visits by Age and Insurance")

plt.show()

# KL divergence

lambda_hat = mod_multi.fittedvalues.values

y = df["doctor_visits"].values

KL_i = np.where(

y == 0,

-y + lambda_hat,

y * np.log(y / lambda_hat) - y + lambda_hat

)<string>:5: RuntimeWarning: divide by zero encountered in log

<string>:5: RuntimeWarning: invalid value encountered in multiplyKL_avg = KL_i.mean()