mindmap

root((Regression

Analysis)

Continuous <br/>Outcome Y

{{Unbounded <br/>Outcome Y}}

)Chapter 3: <br/>Ordinary <br/>Least Squares <br/>Regression(

(Normal <br/>Outcome Y)

{{Nonnegative <br/>Outcome Y}}

)Chapter 4: <br/>Gamma Regression(

(Gamma <br/>Outcome Y)

{{Bounded <br/>Outcome Y <br/> between 0 and 1}}

)Chapter 5: Beta <br/>Regression(

(Beta <br/>Outcome Y)

{{Nonnegative <br/>Survival <br/>Time Y}}

)Chapter 6: <br/>Parametric <br/> Survival <br/>Regression(

(Exponential <br/>Outcome Y)

(Weibull <br/>Outcome Y)

(Lognormal <br/>Outcome Y)

)Chapter 7: <br/>Semiparametric <br/>Survival <br/>Regression(

(Cox Proportional <br/>Hazards Model)

(Hazard Function <br/>Outcome Y)

Discrete <br/>Outcome Y

{{Binary <br/>Outcome Y}}

{{Ungrouped <br/>Data}}

)Chapter 8: <br/>Binary Logistic <br/>Regression(

(Bernoulli <br/>Outcome Y)

8 Binary Logistic Regression

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Explain how Binary Logistic Regression models the probability of a binary outcome using log-odds.

- Describe why Ordinary Least Squares is not appropriate for binary outcomes, and how the logistic function addresses this.

- Fit a binary logistic regression model in both

RandPython. - Interpret log-odds, odds ratios, and predicted probabilities in real-world contexts.

- Evaluate model fit using metrics such as accuracy, confusion matrices, and ROC curves.

- Identify when binary logistic regression is the appropriate tool, and understand its limitations.

8.1 Introduction

In many real-world problems, the outcome we’re trying to predict is not a number — it’s a yes or no, success or failure, clicked or didn’t click. For example:

- Will a student default on a loan given their credit score and income?

- Will a student pass a course based on whether they have a part-time job and how many hours they studied?

- Will a student likely graduate within 4 years, based on their academic record and declared major?

These outcomes are binary: they can take on only two possible values, typically coded as 1 (event occurs) and 0 (event does not occur).

To model such outcomes, we need a regression approach that produces predicted probabilities between 0 and 1 — not arbitrary numbers on the real line. This is where Binary Logistic Regression comes in.

In this chapter, we’ll see how logistic regression:

- Links input variables to the log-odds of the outcome,

- Produces interpretable coefficients (like odds ratios), and

- Helps us make informed predictions in binary classification problems.

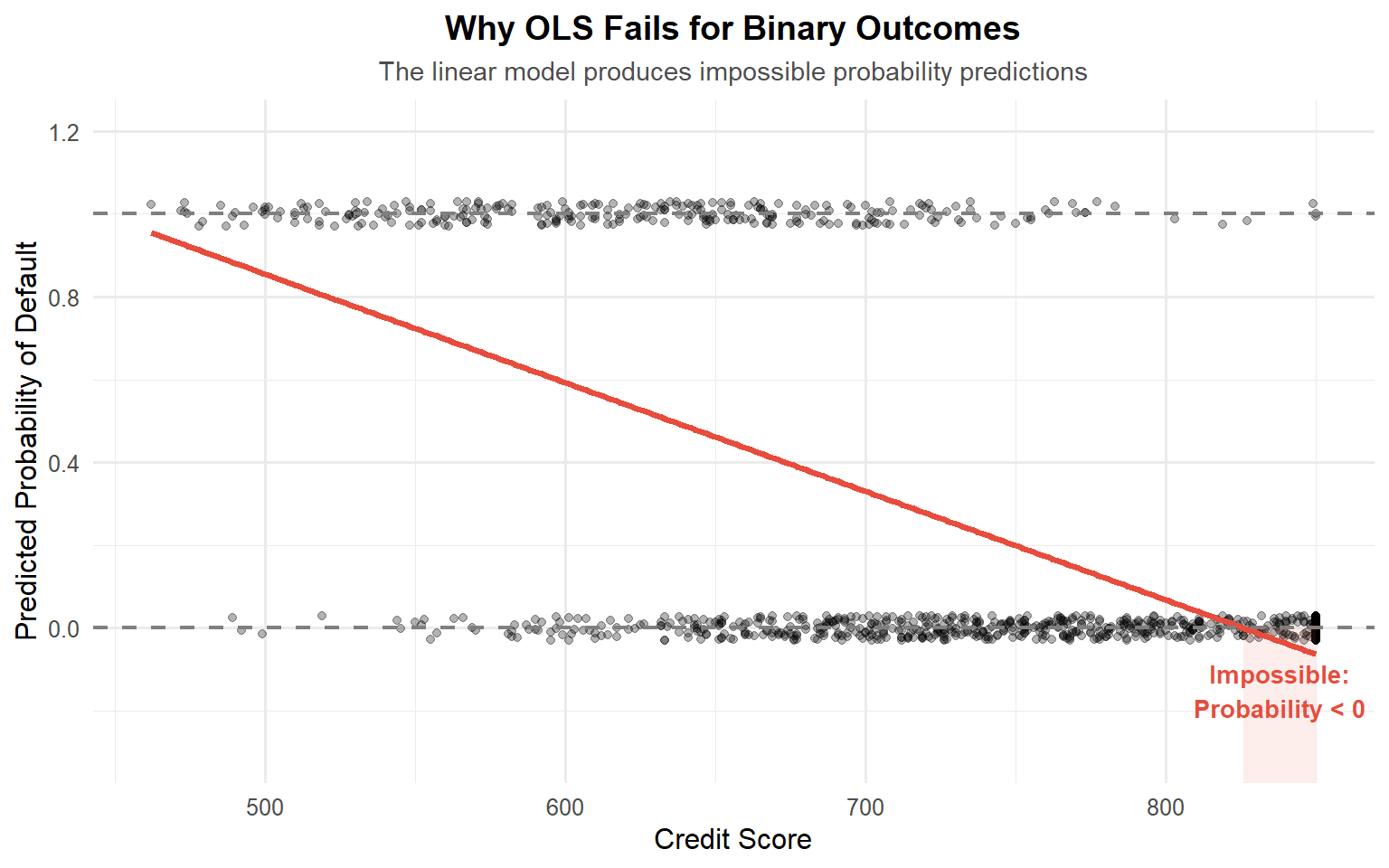

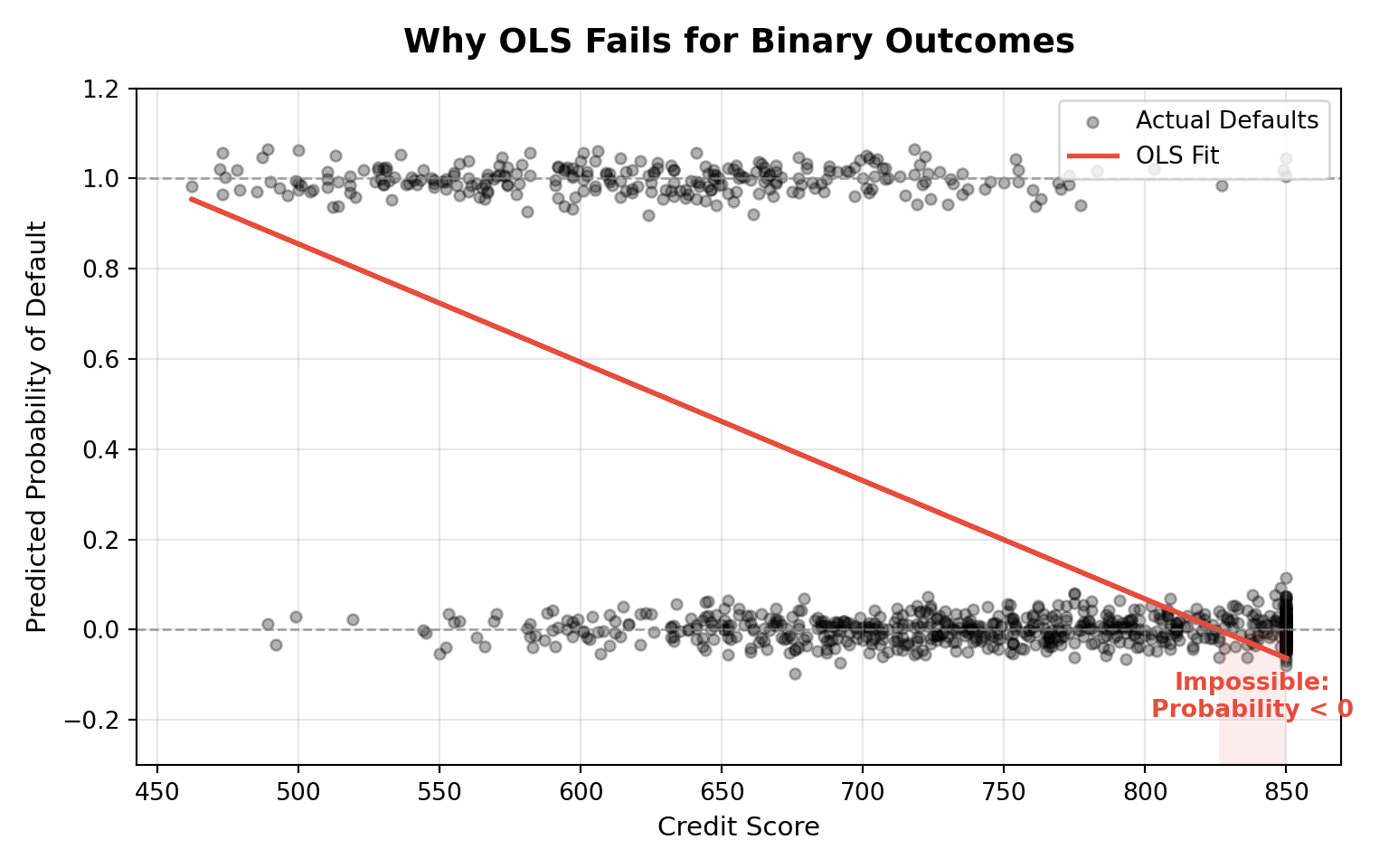

8.2 Why Ordinary Least Squares Fails for Binary Outcomes

To understand the need for logistic regression, consider applying Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) to a binary outcome.

Suppose we are trying to predict whether a student defaulted on a loan (1) or did not default (0) using a continuous predictor like credit_score.

In this chapter we use the BLR (Binary Logistic Regression) dataset, which contains student-level information such as credit score, income, and other demographic/financial variables. Our outcome of interest is defaulted, a binary indicator where 1 means the student defaulted on a loan and 0 means they did not. We’ll start with a single predictor (credit_score) to illustrate the core ideas, then later extend to multiple predictors.

Before diving into the technical reasons why OLS is inappropriate for binary outcomes, let’s look at a simplified version of the dataset we’ll use throughout this chapter:

# Prepare data: numeric default variable and select predictor

blr_data <- BLR %>%

select(credit_score, defaulted) %>%

mutate(defaulted = as.numeric(defaulted))Below is a sample of this dataset:

| credit_score | income | education_years | married | owns_home | age | defaulted | successes | trials |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 850 | 154100 | 16 | 0 | 1 | 56 | 0 | 7 | 10 |

| 606 | 34100 | 13 | 1 | 0 | 31 | 0 | 7 | 10 |

| 846 | 73000 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 0 | 7 | 10 |

| 702 | 41300 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 41 | 1 | 5 | 10 |

| 843 | 50800 | 16 | 1 | 1 | 45 | 0 | 7 | 10 |

| 610 | 33400 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 1 | 3 | 10 |

| 572 | 24600 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 28 | 1 | 3 | 10 |

| 795 | 57700 | 16 | 1 | 1 | 40 | 0 | 7 | 10 |

| 796 | 37100 | 13 | 1 | 0 | 50 | 0 | 8 | 10 |

| 690 | 72300 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 38 | 0 | 8 | 10 |

Now, let’s narrow in on the key variables of interest for this section.

| credit_score | defaulted |

|---|---|

| 850 | 0 |

| 606 | 0 |

| 846 | 0 |

| 702 | 1 |

| 843 | 0 |

| 610 | 1 |

| 572 | 1 |

| 795 | 0 |

| 796 | 0 |

| 690 | 0 |

This dataset allows us to examine whether a student defaulted on a loan (defaulted = 1) based on their credit_score. It’s a classic binary outcome: a “yes” or “no” event.

If we use OLS, we estimate:

\[ \mathbb{E}(Y_i \mid X_i) = \pi_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X_i \]

This means we’re treating the probability of default (\(\pi_i\)) as a linear function of credit score.

However, there are two fundamental issues with using OLS here:

- The linear model can produce predicted values less than 0 or greater than 1 — which doesn’t make sense when modeling a probability.

- OLS assumes constant variance of the residuals, but binary outcomes inherently violate this assumption, because their variance depends on the mean:

\[ \text{Var}(Y_i) = \pi_i(1 - \pi_i) \]

To see this issue in action, let’s try fitting an OLS regression model using our binary outcome and a continuous predictor. While OLS is designed to minimize squared error, it doesn’t account for the discrete nature of the response — which means it can return predicted probabilities below 0 or above 1. In the example below, we use a customer’s credit score to predict the probability of default, and you’ll see how the linear model fails to respect the fundamental constraints of probability.

These limitations make OLS unsuitable for modeling a binary outcome as a probability.

To properly model the probability of the event (here, default), we need a method that:

- Produces predictions strictly between 0 and 1,

- Accounts for the fact that the variance depends on the mean, and

- Connects our predictors to the probability of the event in a way that is easy to interpret.

The key idea is to transform the probability so that it can be modeled as a linear function without breaking these rules.

In the next section, we’ll see how the logit transformation does exactly that.

# ⚠️ This OLS fit is not appropriate for binary outcomes.

# We include it here only to illustrate why logistic regression is needed.

# Load necessary libraries

library(ggplot2)

library(dplyr)

# Prepare data: numeric default variable and select predictor

blr_data <- BLR %>%

select(credit_score, defaulted) %>%

mutate(defaulted = as.numeric(defaulted))

# Fit an OLS model (not ideal for binary outcome)

ols_model <- lm(defaulted ~ credit_score, data = blr_data)

# Add predicted values

blr_data$predicted <- predict(ols_model, newdata = blr_data)

# Plot actual data and OLS-fitted line

plot <- ggplot(blr_data, aes(x = credit_score, y = defaulted)) +

geom_jitter(height = 0.05, width = 0, alpha = 0.4, color = "black") +

geom_line(aes(y = predicted), color = "blue", linewidth = 1.2) +

labs(

title = "OLS Fitted Line on Binary Data",

x = "Credit Score",

y = "Predicted Probability of Default"

) +

coord_cartesian(ylim = c(-0.2, 1.2)) +

theme_minimal() +

theme(plot.title = element_text(hjust = 0.5, face = "bold"))

plot# ⚠️ This OLS fit is not appropriate for binary outcomes.

# We include it here only to illustrate why logistic regression is needed.

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import statsmodels.api as sm

# Extract relevant columns from the BLR dataset

blr = r.data['BLR']

df = blr[['credit_score', 'defaulted']].copy()

df['defaulted'] = df['defaulted'].astype(int)

# Fit an OLS model

X = sm.add_constant(df['credit_score'])

model = sm.OLS(df['defaulted'], X).fit()

df['predicted'] = model.predict(X)

# Plot the actual binary outcomes and OLS predictions

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6, 4))

ax.scatter(df['credit_score'], df['defaulted'], alpha=0.4, color='black', label='Actual Data', s=20)

ax.plot(df['credit_score'], df['predicted'], color='blue', label='OLS Fit', linewidth=2)

ax.set_title("OLS Fitted Line on Binary Data", fontsize=14, fontweight='bold')

ax.set_xlabel("Credit Score")

ax.set_ylabel("Predicted Probability of Default")

ax.set_ylim(-0.2, 1.2)

ax.legend()

plt.grid(True)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

(-0.3, 1.2)

8.3 The Logit Function

In Section 8.2, we saw that modeling probability directly with a linear equation can produce impossible values (less than 0 or greater than 1) and ignores the way variance changes with the mean.

The fix is to apply a transformation that:

- Expands the (0, 1) probability range to the entire real line,

- Is reversible, so we can convert back to probabilities, and

- Preserves the ordering of probabilities.

One transformation that checks all these boxes is the logit function.

8.3.1 Logit: A Link Between Probability and Linear Predictors

The logit function transforms the probability \(\pi_i\) into a value on the entire real line: \[ \text{logit}(\pi_i) = \log\!\left(\frac{\pi_i}{1 - \pi_i}\right) = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X_i \]

This transformation:

- Is monotonic (it preserves order),

- Maps probabilities \(\pi_i \in (0, 1)\) to \((-\infty, \infty)\), and

- Solves the range issue of OLS by letting us fit a linear model in the transformed space.

By modeling the log-odds as a linear function of predictors and then inverting the transformation, we obtain valid predicted probabilities that remain within \([0,1]\).

The logit function is defined as: \[ \text{logit}(\pi_i) = \log\!\left(\frac{\pi_i}{1 - \pi_i}\right) \] It models the log-odds of the outcome as a linear function of predictors.

8.3.2 From Log-Odds Back to Probability

While the model calculates linearly on the log-odds scale, we ultimately want to understand the probability of the outcome (\(\pi_i\)). To do this, we invert the logit function.

The inverse of the logit is the Sigmoid function (also called the logistic function):

\[ \pi_i = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-(\beta_0 + \beta_1 X_i)}} \]

This function takes our linear prediction (\(\beta_0 + \beta_1 X_i\)), which can range from \(-\infty\) to \(+\infty\), and “squashes” it into the range \((0, 1)\). This mathematical trick ensures that no matter how extreme our predictor values get, our predicted probability never exceeds 1 or drops below 0.

8.3.3 Understanding the “S” Shape

The sigmoid function is not just a boundary enforcer; it fundamentally changes how we interpret the relationship between \(X\) and \(Y\). Unlike a straight line, the sigmoid curve is non-linear.

1. The Steep Middle (High Sensitivity) When the probability is near 0.5 (the “tipping point”), the curve is steepest. This means that small changes in the predictor \(X\) result in large changes in the probability \(\pi_i\).

- Context: If a borrower is borderline (e.g., 50/50 chance of default), a small improvement in their credit score can drastically reduce their default risk.

2. The Flat Tails (Diminishing Returns) As the probability approaches 0 or 1, the curve flattens out (asymptotes). In these regions, even large changes in \(X\) result in tiny changes in \(\pi_i\).

- Context: If a borrower has a near-perfect credit score (risk \(\approx 0.01\%\)), increasing their score further makes almost no difference to their probability of default. The model recognizes that they are already “maxed out” on safety.

This captures a realistic property of many binary outcomes: interventions are most effective when the outcome is uncertain.

This transformation lets us use a linear predictor on the log-odds scale and then recover valid probabilities.

This idea forms the basis of binary logistic regression, introduced next.

In OLS (linear regression), the slope \(\,\beta_1\,\) is a constant change in the mean response: \[ \mathbb{E}[Y \mid x+1] - \mathbb{E}[Y \mid x] = \beta_1. \]

In logistic regression, the relationship is linear on the log-odds (logit) scale: \[ \log\!\left(\frac{\pi(x)}{1-\pi(x)}\right)=\beta_0+\beta_1 x. \] So \(\beta_1\) is still a constant slope—but it is constant in log-odds: a one-unit increase in \(x\) adds \(\beta_1\) to the log-odds (equivalently, it multiplies the odds by \(e^{\beta_1}\)), holding other predictors fixed.

What isn’t constant is the change in probability. The marginal effect on probability depends on \(\pi(x)\): \[ \frac{d\pi(x)}{dx}=\beta_1\,\pi(x)\big(1-\pi(x)\big), \] which is largest near \(\pi(x)=0.5\) and shrinks as \(\pi(x)\) approaches 0 or 1.

8.3.4 The Logistic Function and Its Shape (Code)

The following plot illustrates this behavior. Notice how the linear model (red dashed line) marches blindly past 0 and 1, while the logistic model (blue solid line) respects the boundaries and shows the characteristic “S” shape.

# Logistic vs Linear fit demo

set.seed(1)

# Grid of linear predictor values (η)

eta <- seq(-4, 4, length.out = 400)

# Logistic sigmoid: π(η)

pi <- 1 / (1 + exp(-eta))

# Naive linear "probability" for comparison

# passes through (0, 0.5) with moderate slope

p_lin <- 0.5 + 0.25 * eta

df <- data.frame(

eta = eta,

sigmoid = pi,

linear = p_lin

)

library(ggplot2)

ggplot(df, aes(x = eta)) +

# Logistic S-curve

geom_line(aes(y = sigmoid), linewidth = 1.4, color = "steelblue") +

# Naive linear line

geom_line(aes(y = linear), linewidth = 1.1, linetype = "dashed",

color = "#E74C3C") +

# Vertical marker for steepest change near π ≈ 0.5

geom_segment(aes(x = 0, xend = 0,

y = plogis(-0.7), yend = plogis(0.7)),

colour = "gray40", linewidth = 0.7) +

annotate("text", x = 0.7, y = 0.55,

label = "Steepest change\nat π ≈ 0.5",

size = 3.5, hjust = 0, color = "gray30") +

coord_cartesian(ylim = c(0, 1)) +

scale_y_continuous(breaks = seq(0, 1, by = 0.25)) +

labs(

x = "Linear predictor (η = β0 + β1 X)",

y = "Probability (π)",

title = "The Sigmoid 'S-Curve' vs. Linear Fit",

subtitle = "Logistic regression captures diminishing returns at the extremes",

caption = "Blue: Logistic Sigmoid (Valid Probabilities). Red: Naive Linear (Violates Bounds)."

) +

theme_minimal(base_size = 12) +

theme(

plot.title = element_text(hjust = 0.5, face = "bold", size = 14),

plot.subtitle = element_text(hjust = 0.5, size = 11, colour = "gray40")

)import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy.special import expit # logistic / sigmoid

np.random.seed(1)

# Grid of linear predictor values (η)

eta = np.linspace(-4, 4, 400)

# Logistic sigmoid π(η)

pi = expit(eta)

# Naive linear "probability" (same as R: 0.5 + 0.25η)

p_lin = 0.5 + 0.25 * eta

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 5))

# Logistic S-curve

plt.plot(eta, pi, label="Logistic Sigmoid (Valid $\pi$)",

linewidth=2.0, color="steelblue")

# Naive linear line

plt.plot(eta, p_lin, "--", label="Naive Linear (Violates Bounds)",

linewidth=1.5, color="#E74C3C")

# Vertical marker around steepest change near π ≈ 0.5

y_lo, y_hi = expit(-0.7), expit(0.7)

plt.plot([0, 0], [y_lo, y_hi], color="gray40", linewidth=1.0)

plt.text(0.7, 0.55, "Steepest change\nat $\pi \\approx 0.5$",

fontsize=10, color="gray30", ha="left", va="center")

plt.ylim(0, 1)

plt.yticks(np.arange(0, 1.01, 0.25))

plt.xlabel(r"Linear predictor ($\eta = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X$)")

plt.ylabel(r"Probability ($\pi$)")

plt.title("The Sigmoid 'S-Curve' vs. Linear Fit")

plt.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.legend(loc="lower right")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()8.4 Case Study: Understanding Financial Behaviors

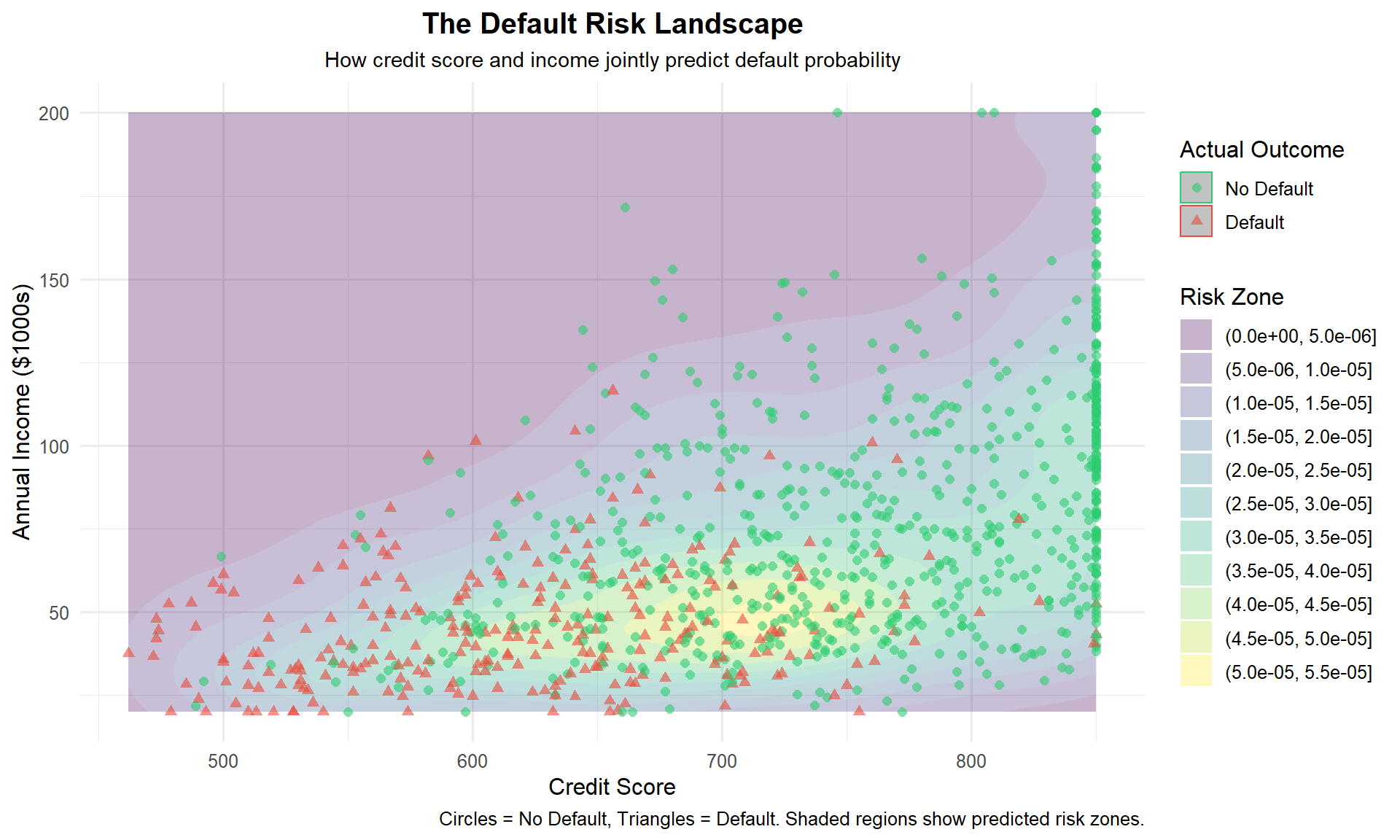

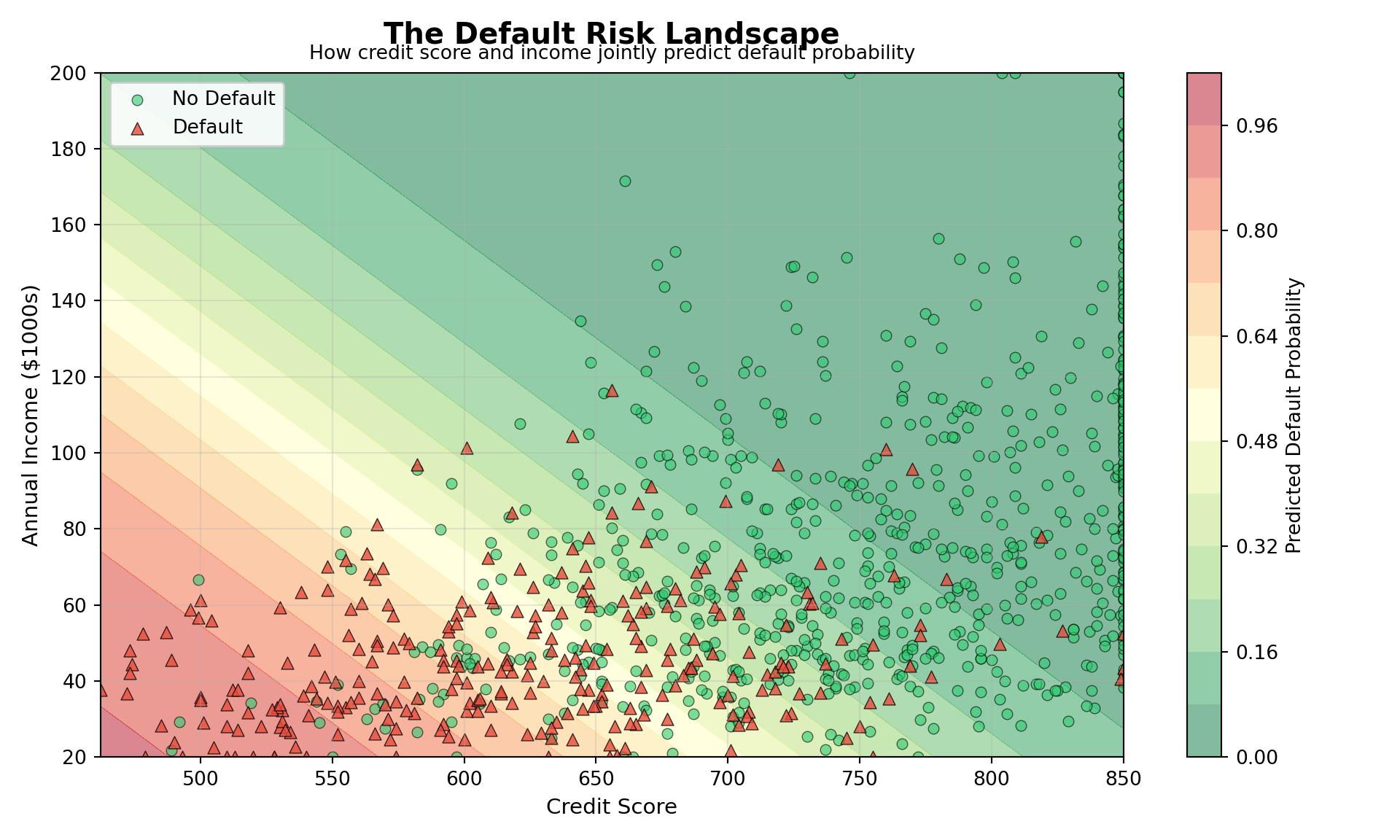

Statistical models are most useful when they connect to a real-world problem. In this case study, we use binary logistic regression to model default risk—the probability that a student defaults on a loan.

8.4.1 Case Study Setup: Data + Goal

We’ll use the Logistic_Regression dataset (packaged in cookbook). The outcome is:

-

defaulted(binary:1 = default,0 = no default)

and we model the probability of default for each student, \(\pi_i = P(Y_i = 1 \mid \mathbf{x}_i)\), using a mix of predictors such as:

-

credit_score(numeric; higher typically means lower risk) -

income(numeric; annual income) -

age(numeric) -

loan_amount(numeric) -

student(categorical: yes/no)

Banks and lenders face a practical question:

Given a customer’s financial history, how risky is this loan?

Even though the final decision is “approve” or “deny,” the key modeling goal is to estimate a probability of default (risk). That probability can later be converted into a decision using a chosen threshold (e.g., “approve only if \(\hat{\pi}_i < 0.10\)”).

Why probability matters: asymmetric costs

Errors are not equally costly:

-

False positive: predict default, but the customer would have paid.

Cost: opportunity cost (lost interest). -

False negative: predict safe, but the customer defaults.

Cost: potential loss of principal (and associated costs).

Because false negatives are often more expensive, we care about a calibrated probability \(\hat{\pi}_i\), not just a yes/no label.

8.4.2 Study Design and Data Prep

Before fitting the model, we set up the analysis and prepare the data.

Study design (high-level)

- Predictors: a mix of continuous and categorical variables.

-

Outcome: binary (

defaulted). -

Assumptions / modelling requirements:

- Independence: observations are (approximately) independent.

- Linearity in the log-odds: predictors relate linearly to the log-odds of default.

- No perfect multicollinearity (identifiability): predictors must not be perfectly redundant (e.g., one column is an exact linear combination of others), so coefficients are uniquely estimable.

Data preparation steps

We’ll do three practical steps that help ensure fair evaluation and stable estimation:

- Check class balance. If defaults are rare, accuracy alone can be misleading.

- Split into training/testing sets to evaluate generalization and reduce overfitting.

- Stratify the split so the default rate is similar in both sets.

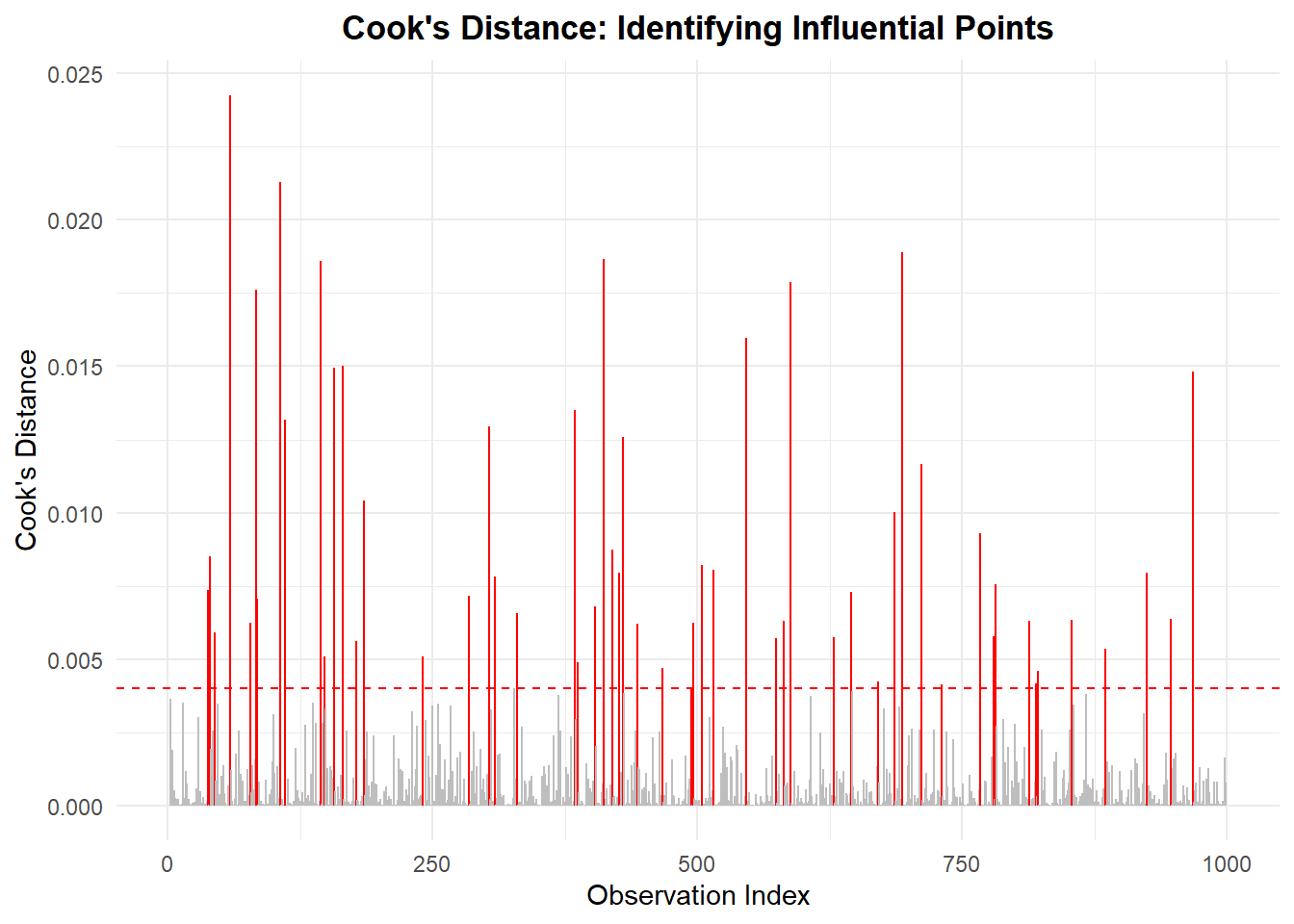

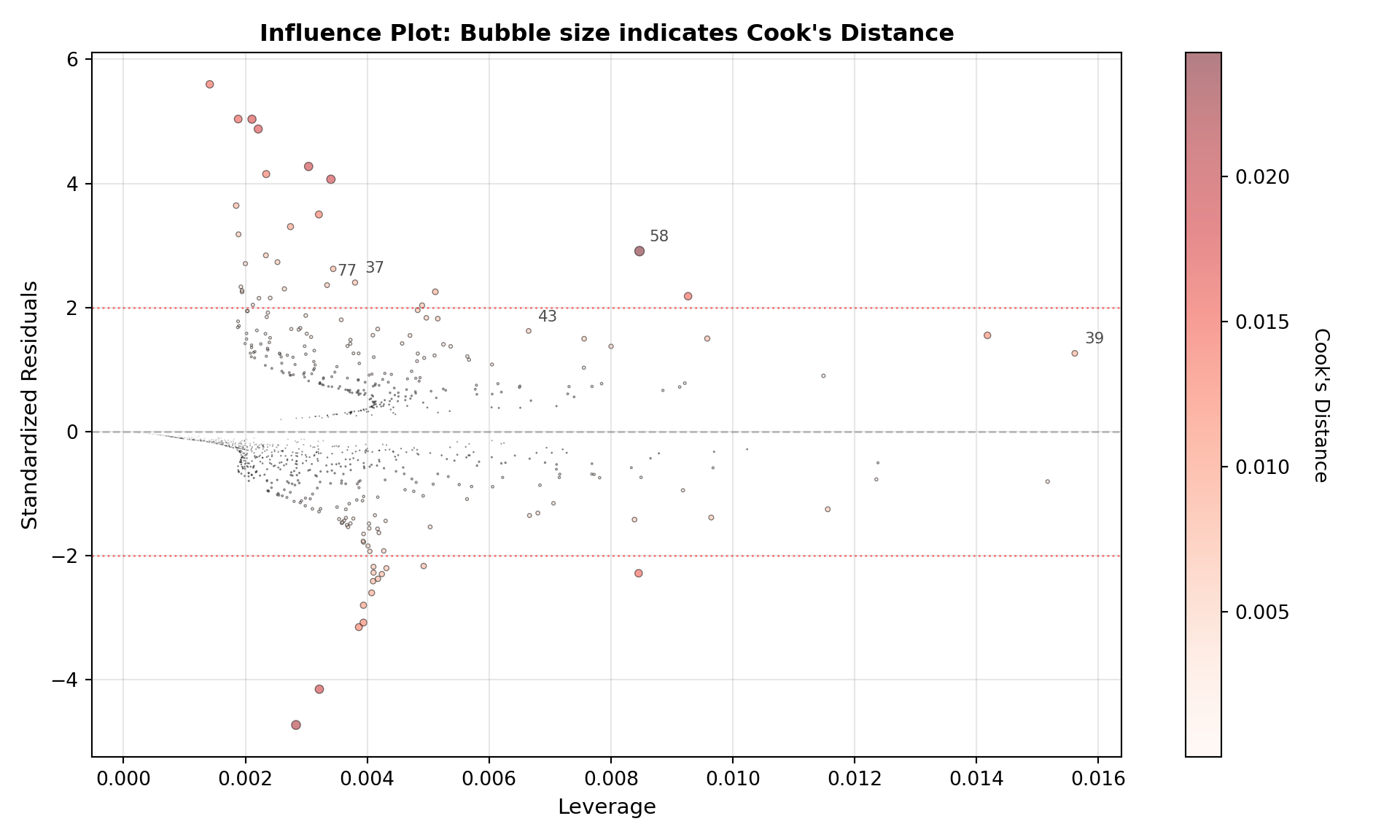

Influential points and outliers

All regression-style models can be influenced by unusual observations. In logistic regression, the most important cases are often high-leverage points (unusual predictor values) and situations close to separation (predictors almost perfectly predict the outcome), both of which can strongly affect the fitted probabilities.

Before modeling, it’s worth checking for:

- Data entry errors (impossible values).

- Extreme leverage points (legitimate but unusually large/small predictor values that may disproportionately influence the fit).

8.4.3 Data Preparation in Action

Below, we check the default rate and create a stratified train/test split.

library(rsample) # Part of tidymodels for splitting

library(dplyr)

# 1. Check Class Imbalance

# Notice if defaults are rare (e.g., < 10%)

prop.table(table(BLR$defaulted))

# 2. Stratified Split

# We use 'strata = defaulted' to ensure both sets have the same % of defaults

set.seed(123)

split <- initial_split(BLR, prop = 0.70, strata = defaulted)

train_data <- training(split)

test_data <- testing(split)

# 3. Verify the split

nrow(train_data)

nrow(test_data)import pandas as pd

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

# 1. Check Class Imbalance

print(df['defaulted'].value_counts(normalize=True))

# 2. Stratified Split

# We use 'stratify=y' to ensure both sets have the same % of defaults

X = df.drop(columns=['defaulted'])

y = df['defaulted']

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(

X, y,

test_size=0.3,

random_state=123,

stratify=y # Crucial for imbalanced data

)

# 3. Verify the split

print(f"Training set shape: {X_train.shape}")

print(f"Testing set shape: {X_test.shape}")8.5 Fitting the Binary Logistic Regression Model

Now that we’ve prepared the data, we fit the model. Our goal is to estimate the unknown parameters (\(\beta\)) that link our predictors (like credit_score) to the probability of default.

8.5.1 Model Specification

We define the relationship between the predictors and the probability of default \(\pi_i\) as:

\[ \log\!\left(\frac{\pi_i}{1 - \pi_i}\right) = \beta_0 + \beta_1\,\text{credit\_score}_i + \beta_2\,\text{income}_i + \dots + \beta_k X_{ki} \]

Here is what the parameters entail:

- \(\pi_i\): The probability that the \(i\)-th student defaults.

- \(\beta_0\) (The Intercept): The log-odds of default when all predictors are zero (often outside the meaningful range of the data, so mainly a baseline reference).

-

\(\beta_1, \dots, \beta_k\) (The Slopes): For a one-unit increase in the corresponding predictor \(X_j\) (e.g.,

credit_scoreorincome), \(\beta_j\) is the change in the log-odds of default, holding all other predictors fixed. Equivalently, the odds are multiplied by \(e^{\beta_j}\).

8.5.2 Fitting the Model

To estimate these \(\beta\) parameters, we use Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE).

In R, we use the glm() function (Generalized Linear Model). Crucially, we must specify family = binomial.

Why

family = binomial? Standard regression (OLS) assumes the target variable follows a Normal (Gaussian) distribution. However, our target is binary (0/1), which follows a Bernoulli/Binomial distribution. This argument tells the software to switch from “Least Squares” to “Maximum Likelihood” using the binomial distribution.Why Logit? By default,

family = binomialuses the logit link function. While other links exist (like probit), the logit is preferred for its interpretability (odds ratios) and mathematical properties.

import statsmodels.api as sm

# 1. Define Predictors (X) and Target (y)

# Note: We access the R dataframe 'BLR' using 'r.BLR'

df = r.BLR

X = df[['credit_score', 'income', 'age', 'loan_amount', 'student']]

y = df['defaulted']

# 2. Add Intercept manually (Statsmodels does not add it by default)

X = sm.add_constant(X)

# 3. Fit the Logit model

model = sm.Logit(y, X).fit()

print(model.summary())8.5.3 Model Output Interpretation

The output table provides the Estimate (the \(\beta\) coefficients) for each predictor.

- Positive Coefficient (+): As this variable increases, the log-odds of default increase (Higher Risk).

- Negative Coefficient (-): As this variable increases, the log-odds of default decrease (Lower Risk).

In the next section, we will convert these raw log-odds into Odds Ratios, which are much easier to interpret for business decisions.

8.6 Interpreting Model Results: Log-Odds and Odds Ratios

In the previous section, we fit a model with several predictors. To clearly demonstrate how to interpret the coefficients, let’s focus on a simplified model using just two key variables: credit_score and income.

8.6.1 The “Log-Odds” Output

By default, logistic regression software reports coefficients \(\hat{\beta}\) on the log-odds (logit) scale. In other words, the model is linear in the quantity \[ \log\!\left(\frac{\pi_i}{1-\pi_i}\right), \] not directly in \(\pi_i\). This is why the printed coefficients can feel unintuitive: a change like \(\hat{\beta}=-0.004\) is a change in log-odds, not a direct “percent change in probability.”

Practically: - In R, these values appear in the estimate column. - In Python (statsmodels), they appear in the coef (or params) output.

A good mental model is: each coefficient tells you how the log-odds move when that predictor increases by one unit, holding the other predictors fixed.

8.6.2 From Log-Odds to Odds Ratios

To make coefficients easier to interpret, we often exponentiate them to get odds ratios (ORs): \[ \text{OR}_j = e^{\hat{\beta}_j}. \] Exponentiation converts “additive changes in log-odds” into “multiplicative changes in odds.”

- If \(\text{OR}_j > 1\), then increasing \(X_j\) is associated with higher odds of the event (\(Y=1\)), holding other predictors fixed.

- If \(\text{OR}_j < 1\), then increasing \(X_j\) is associated with lower odds of the event.

- If \(\text{OR}_j = 1\), then there is no change in odds associated with \(X_j\) (at least in this fitted model).

Importantly, the OR interpretation is always “per one-unit increase in the corresponding predictor.” If the unit is very small (like $1 of income), the OR can look like 1.0000 even when the effect is real.

8.6.3 A Simplified Model for Interpretation

To demonstrate coefficient interpretation clearly, we focus on a simplified model using two predictors: credit_score and income: \[

\log\!\left(\frac{\pi_i}{1-\pi_i}\right)

= \beta_0 + \beta_1\,\texttt{credit\_score}_i + \beta_2\,\texttt{income}_i.

\] Here, \(\beta_1\) is the log-odds change associated with a one-point increase in credit score (holding income fixed), and \(\beta_2\) is the log-odds change associated with a one-dollar increase in income (holding credit score fixed).

Below, we fit the simplified model and compute odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals.

# Fit a simplified model for clear interpretation

fit_simple <- glm(

defaulted ~ credit_score + income,

data = BLR,

family = binomial(link = "logit")

)

# We use broom::tidy to easily extract coefficients

library(broom)

coef_table <- tidy(fit_simple)

# Calculate Wald confidence intervals (more stable than profile likelihood)

ci <- confint.default(fit_simple, level = 0.95)

coef_table$conf.low <- ci[, 1]

coef_table$conf.high <- ci[, 2]

# Calculate Odds Ratios (OR) by exponentiating estimates and CIs

coef_table$odds_ratio <- exp(coef_table$estimate)

coef_table$or_low <- exp(coef_table$conf.low)

coef_table$or_high <- exp(coef_table$conf.high)

# Display the table

knitr::kable(

coef_table[, c("term","estimate","std.error","p.value","odds_ratio","or_low","or_high")],

digits = 4,

col.names = c("Term","Log-Odds (β)","SE","p","Odds Ratio","OR 2.5%","OR 97.5%")

)import pandas as pd

import statsmodels.api as sm

import numpy as np

# Access the data from R

df = r.BLR

X = sm.add_constant(df[['credit_score', 'income']])

y = df['defaulted']

# Fit the simplified model

logit_model = sm.Logit(y, X).fit(disp=False)

# 1. Extract Parameters (Log-Odds)

params = logit_model.params

conf = logit_model.conf_int()

# 2. Calculate Odds Ratios (OR)

# We exponentiate the log-odds to get the OR

odds_ratios = np.exp(params)

conf_or = np.exp(conf)

# 3. Create a clean summary table

results_table = pd.DataFrame({

"Log-Odds (β)": params,

"p-value": logit_model.pvalues,

"Odds Ratio": odds_ratios,

"OR 2.5%": conf_or[0],

"OR 97.5%": conf_or[1]

})

print(results_table.round(4))Interpretation of the Output

- Intercept: usually ignored in interpretation.

-

credit_score: If the coefficient is \(\beta \approx -0.01\), then \(\text{OR} \approx 0.99\).

- Meaning: For every 1-point increase in credit score, the odds of default are multiplied by 0.99 (a ~1% decrease), holding income constant.

- income: If the \(\text{OR} \approx 1.00\), the effect per dollar is tiny. In such cases, it is often useful to rescale the variable (e.g., income in $10k units) to see a meaningful effect size.

8.7 From Log-Odds to Probabilities (Simple Model)

To fully understand how the model converts abstract “log-odds” into a tangible “probability,” it is best to start with the simplest case: one predictor.

In a simple binary logistic regression, the relationship is:

\[ \hat{\pi} = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-(\hat{\beta}_0 + \hat{\beta}_1 X)}} \]

Below, we fit a model using only credit_score to predict default. We will then calculate the predicted probability (\(\hat{\pi}\)) for a student with a Low, Median, and High credit score.

# 1. Fit a Simple Model (1 Predictor)

fit_simple <- glm(defaulted ~ credit_score, data = BLR, family = binomial)

# 2. Define Scenarios: Low, Median, and High Credit Score

# We pick the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles

qs <- quantile(BLR$credit_score, probs = c(0.25, 0.5, 0.75), na.rm = TRUE)

scenarios <- data.frame(

scenario = c("Low (25th %)", "Median (50th %)", "High (75th %)"),

credit_score = as.numeric(qs)

)

# 3. Calculate Linear Predictor (Log-Odds) and Probability

# type = "link" gives log-odds (eta)

# type = "response" gives probability (pi)

scenarios$log_odds <- predict(fit_simple, newdata = scenarios, type = "link")

scenarios$prob_pi <- predict(fit_simple, newdata = scenarios, type = "response")

# Display Results

knitr::kable(

scenarios,

digits = 3,

col.names = c("Scenario", "Credit Score", "Log-Odds (η)", "Probability (π)")

)import pandas as pd

import statsmodels.api as sm

import numpy as np

# 1. Fit a Simple Model (1 Predictor)

# We define X with only credit_score

X_simple = sm.add_constant(df[['credit_score']])

y = df['defaulted']

model_simple = sm.Logit(y, X_simple).fit(disp=0)

# 2. Define Scenarios

qs = df['credit_score'].quantile([0.25, 0.5, 0.75]).values

scenarios = pd.DataFrame({

'const': 1.0,

'credit_score': qs

}, index=["Low (25th %)", "Median (50th %)", "High (75th %)"])

# 3. Calculate Linear Predictor and Probability manually

# eta = beta0 + beta1 * score

eta = np.dot(scenarios, model_simple.params)

# pi = 1 / (1 + e^-eta)

pi = 1 / (1 + np.exp(-eta))

# Display Results

results = pd.DataFrame({

"Credit Score": scenarios['credit_score'],

"Log-Odds (η)": eta,

"Probability (π)": pi

})

print(results.round(3))Interpretation

- At Low Credit Score: The log-odds are likely positive (or less negative), resulting in a higher probability (\(\pi\)) of default.

- At High Credit Score: The log-odds become strongly negative. Because of the exponent in the denominator (\(e^{-\text{negative}}\) is large), the probability \(\pi\) shrinks toward 0.

This demonstrates the inverse relationship: as credit score goes up, the probability of default goes down, following the S-curve shape we saw earlier.

Next Steps: Now that we understand the mechanics of the simple model, we can expand our view. Real-world problems are rarely caused by a single factor. In the following sections, we will add more variables (like income and student status) to build a multiple logistic regression model.

8.8 Data Preparation and Wrangling

Before we can train a model, we must bridge the gap between how data is collected and how a regression model consumes it. Raw data is often messy, incomplete, or stored in text formats that mathematical algorithms cannot process.

Data wrangling ensures our inputs are reliable (free of errors), complete (no missing values), and structured (numerical matrices). Without this step, even the most sophisticated algorithm will fail—a principle known as “Garbage In, Garbage Out.”

8.8.1 Handling Missing Data

Real-world datasets frequently have gaps—a borrower might leave the “Income” field blank. Logistic regression requires a complete set of observations; it cannot calculate a coefficient for a “blank” space.

We must first check the extent of the problem. If only a few rows have missing data, we typically remove them.

When data is missing, you have three main options:

- Deletion (Complete Case Analysis): If missingness is rare (<5% of data) and random, simply remove those rows. This is the most common approach in introductory texts.

- Imputation: Replace missing values with the mean, median, or a value predicted by other variables. This preserves sample size but adds complexity.

-

Flagging: Create a new binary variable (e.g.,

income_missing = 1) to model the missingness explicitly.

8.8.2 Encoding Categorical Variables

Logistic regression works with matrices of numbers. It cannot mathematically multiply a coefficient \(\beta\) by the text string “Married.”

To fix this, we perform One-Hot Encoding (or Dummy Encoding). This converts a categorical variable into a binary 0/1 flag.

-

Original:

student = "Yes" -

Encoded:

student_yes = 1

Note on the “Dummy Variable Trap” (Intercept + both levels).

If student has two categories (Yes/No), a common encoding is to create two indicators: student_yes and student_no. However, if your model includes an intercept (which is the default in both R and Python), you must not include indicators for all categories. Why? Because for every row, \[

\text{student\_yes} + \text{student\_no} = 1,

\] and the intercept column is also a column of ones. That means one column can be written as an exact linear combination of the others (perfect multicollinearity), so the design matrix is not full rank.

In practice, we avoid this by choosing a reference level and dropping one indicator. The effect of the reference level is absorbed into the intercept, and the remaining coefficient(s) are interpreted relative to that reference group. For example, if “No” is the reference, then the coefficient on student_yes compares students to non-students, holding other predictors fixed.

8.8.3 Splitting the Data

Finally, as discussed in the study design, we split our clean, encoded dataset into training and testing sets to evaluate performance fairly.

library(dplyr)

library(rsample)

# 1. Handling Missing Data

# We check for NAs and, for this chapter, remove incomplete rows

sum(is.na(BLR))

BLR_clean <- na.omit(BLR)

# 2. Encoding

# R handles factor encoding automatically in glm(),

# but it is good practice to ensure variables are factors.

BLR_clean <- BLR_clean %>%

mutate(

student = as.factor(student),

married = as.factor(married),

owns_home = as.factor(owns_home)

)

# 3. Splitting (Stratified to handle class imbalance)

set.seed(123)

split <- initial_split(BLR_clean, prop = 0.7, strata = defaulted)

train_data <- training(split)

test_data <- testing(split)import pandas as pd

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

# 1. Handling Missing Data

# Drop rows with any missing values

df_clean = df.dropna().copy()

# 2. Encoding Categorical Variables

# We use pd.get_dummies to convert text categories to 0s and 1s.

# drop_first=True prevents the "Dummy Variable Trap" (e.g., keeps 'student_Yes', drops 'student_No')

df_clean = pd.get_dummies(df_clean, columns=['student', 'married', 'owns_home'], drop_first=True)

# Display the new columns to verify

print(df_clean.head())

# 3. Splitting (Stratified)

X = df_clean.drop(columns=['defaulted'])

y = df_clean['defaulted']

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(

X, y, test_size=0.3, random_state=123, stratify=y

)8.9 Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA)

Before fitting a logistic regression, we need to understand the structure of our data. Exploratory analysis helps us spot patterns, distributions, and potential issues.

8.9.1 Classifying Variables

To select the appropriate modeling technique, we must first classify our variables. In this analysis, defaulted is our binary outcome, and the remaining variables serve as regressors (explanatory variables).

| Variable | Type | Role | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

defaulted |

Categorical (Binary) | Outcome (\(Y\)) | \(1=\) Default, \(0=\) No Default |

credit_score |

Continuous (Integer) | Regressor (\(X\)) | Credit rating (300-850) |

income |

Continuous | Regressor (\(X\)) | Annual income in CAD |

age |

Continuous (Integer) | Regressor (\(X\)) | Borrower age in years |

loan_amount |

Continuous | Regressor (\(X\)) | Size of loan in CAD |

education_years |

Count / Discrete | Regressor (\(X\)) | Years of schooling |

married |

Categorical (Nominal) | Regressor (\(X\)) | Marital status |

owns_home |

Categorical (Nominal) | Regressor (\(X\)) | Home ownership status |

8.9.2 Visualizing Distributions

-

Continuous regressors (e.g.,

credit_score,income) can be visualized with histograms or density plots, split by default status. -

Categorical regressors (e.g.,

married,owns_home) can be compared with barplots of default rates.

8.9.3 Exploring Relationships with Binary Outcome

Boxplots or violin plots of credit_score by default status, or barplots of default rates by home ownership, help reveal potential relationships. We also check correlations among continuous regressors to watch for multicollinearity.

library(ggplot2)

library(ggcorrplot)

# Boxplot of credit score by default

ggplot(BLR, aes(x = as.factor(defaulted), y = credit_score)) +

geom_boxplot() +

labs(x = "Defaulted", y = "Credit Score",

title = "Credit Score Distribution by Default Status")

# Barplot of default by home ownership

ggplot(BLR, aes(x = as.factor(owns_home), fill = as.factor(defaulted))) +

geom_bar(position = "fill") +

labs(x = "Owns Home", y = "Proportion",

fill = "Defaulted",

title = "Default Rates by Home Ownership")

# Correlation heatmap (Numeric regressors only)

corr <- cor(BLR[,c("credit_score","income","education_years","age")])

ggcorrplot(corr, lab = TRUE)import seaborn as sns

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Boxplot credit score by default

sns.boxplot(data=df, x="defaulted", y="credit_score")

plt.title("Credit Score Distribution by Default Status")

plt.show()

# Barplot default by home ownership

sns.barplot(data=df, x="owns_home", y="defaulted", errorbar=None)

plt.title("Default Rates by Home Ownership")

plt.show()

# Correlation heatmap

corr = df[['credit_score','income','education_years','age']].corr()

sns.heatmap(corr, annot=True, cmap="coolwarm")

plt.title("Correlation Heatmap of Continuous Regressors")

plt.show()8.9.4 What the Correlation Plot Tells Us (and What It Doesn’t)

A correlation plot is a quick way to understand which predictors move together and whether any variables might be partially redundant. Here are the main takeaways we look for:

- Redundant predictors (multicollinearity risk): If two predictors are very strongly correlated (near \(|r|=1\)), they carry similar information. Including both can make coefficient estimates less stable (larger standard errors), which can make interpretation harder even if predictions remain decent.

-

Expected directions and plausibility: Some relationships should match intuition (e.g., higher

credit_scoretypically associated with lower default risk). If a relationship looks surprising, it can be a sign to double-check coding, units, or data quality. - Model-building guidance (not a rule): Correlation is not a “keep/drop” rule by itself. Logistic regression uses conditional relationships (each coefficient is “holding others fixed”), so a variable can have weak marginal correlation and still be important once other predictors are included.

Finally, remember that correlation does not establish causality, and it does not capture non-linear relationships. We use this plot as a diagnostic for feature relationships and potential modeling issues—not as a conclusion about what “causes” default.

8.10 Data Modelling

With EDA complete, we’re ready to specify a logistic regression model. The outcome is binary (defaulted \(\in \{0,1\}\)), so instead of predicting \(Y_i\) directly, we model the probability of default \(\pi_i = P(Y_i=1\mid \mathbf{x}_i)\).

8.10.1 Model setup: distribution + link

In logistic regression we assume: \[ Y_i \sim \text{Bernoulli}(\pi_i), \] meaning each observation is a “yes/no” outcome with success probability \(\pi_i\).

We connect predictors to \(\pi_i\) through the logit link: \[ \log\!\left(\frac{\pi_i}{1-\pi_i}\right) = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X_{1i} + \beta_2 X_{2i} + \dots + \beta_k X_{ki}. \] This expresses a linear model for the log-odds, which guarantees the implied probabilities stay in \((0,1)\).

A common point of confusion is the missing error term \(\epsilon\). In OLS, the error term represents noise around a continuous mean. In logistic regression, randomness is already built into the Bernoulli outcome: even if two people have the same predicted probability \(\pi_i\), the realized outcome can differ because \(Y_i\) is a probabilistic “coin flip” with probability \(\pi_i\).

8.10.2 Parameters and interpretation scope

If we fit a model with \(k\) predictors (regressors), we estimate \(k+1\) parameters: one intercept \(\beta_0\) and one coefficient for each predictor. Each coefficient \(\beta_j\) describes the change in log-odds associated with a one-unit increase in its corresponding predictor \(X_j\), holding the other predictors fixed.

Below, we fit a multivariable model and inspect the output in both R and Python.

import statsmodels.api as sm

# Define Regressors (X) and Outcome (y)

# Ensure categorical variables are encoded (if not done in wrangling step)

X = df[['credit_score','income','married_Yes','owns_home_Yes']]

X = sm.add_constant(X)

y = df['defaulted']

logit_model = sm.Logit(y, X).fit()

print(logit_model.summary())8.11 Estimation

Under a model with \(k\) regressors, the coefficients \(\beta_0,\beta_1,\ldots,\beta_k\) are unknown and must be estimated from the data.

8.11.1 Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE)

Because our outcome \(Y_i\) follows a Bernoulli distribution with probability \(\pi_i\), we cannot use Least Squares. Instead, we use Maximum Likelihood Estimation.

We seek the values of \(\beta\) that maximize the likelihood of observing the data we actually collected. The likelihood function is:

\[ L(\boldsymbol\beta)=\prod_{i=1}^n \pi_i^{y_i}(1-\pi_i)^{1-y_i} \] Where \(\pi_i\) is connected to our regressors via the inverse-logit:

\[\pi_i=\frac{e^{\beta_0 + \dots + \beta_k X_{ki}}}{1+e^{\beta_0 + \dots + \beta_k X_{ki}}} \] The computer solves this using an iterative algorithm (Newton-Raphson) to find the \(\hat{\beta}\) values that make the observed defaults most probable.

8.12 Inference

After estimating a logistic regression model, we often want to know whether predictors are statistically significant — i.e., whether they have a meaningful relationship with the probability of default. In logistic regression, inference is based on the likelihood framework.

8.12.1 Wald Tests

The Wald test checks whether an individual coefficient is significantly different from zero. For example, we can test whether credit_score has a nonzero effect on the odds of default. The test statistic is the ratio of the estimated coefficient to its standard error. In our loan-default example, the model summary below reports Wald tests for both credit_score and income.

8.12.2 Likelihood Ratio Tests

We can also compare nested models (e.g., model with credit_score only vs. model with credit_score + income) using the likelihood ratio (LR) test. This evaluates whether adding predictors significantly improves model fit. The R and Python output below show an LR test comparing a model with only credit_score to a model with both credit_score and income.

8.12.3 Confidence Intervals

Finally, we often report confidence intervals for odds ratios. For example, if the odds ratio for credit score is 0.99 with a 95% CI [0.98, 0.995], we can say with confidence that higher credit scores reduce the odds of default.

# Logistic regression

logit_model <- glm(defaulted ~ credit_score + income,

data = BLR, family = binomial)

# Wald test results are included in summary

summary(logit_model)

# Confidence intervals for odds ratios

exp(cbind(OR = coef(logit_model), confint(logit_model)))

# Likelihood ratio test for nested models

model1 <- glm(defaulted ~ credit_score, data = BLR, family = binomial)

anova(model1, logit_model, test = "Chisq")import statsmodels.api as sm

import numpy as np

from scipy.stats import chi2

df = r.data['BLR'].copy()

df['defaulted'] = df['defaulted'].astype(int)

# Full model

X_full = sm.add_constant(df[['credit_score','income']])

y = df['defaulted']

model_full = sm.Logit(y, X_full).fit()

# Wald test (coeff / SE)

wald_stats = (model_full.params / model_full.bse)**2

print("Wald test chi2 values:\n", wald_stats)

# Confidence intervals for odds ratios

conf = model_full.conf_int()

odds_ratios = np.exp(model_full.params)

conf_exp = np.exp(conf)

print("Odds Ratios:\n", pd.DataFrame({"OR": odds_ratios,

"2.5%": conf_exp[0],

"97.5%": conf_exp[1]}))

# Likelihood ratio test vs simpler model

X_simple = sm.add_constant(df[['credit_score']])

model_simple = sm.Logit(y, X_simple).fit()

LR_stat = 2 * (model_full.llf - model_simple.llf)

df_diff = model_full.df_model - model_simple.df_model

p_value = chi2.sf(LR_stat, df_diff)

print(f"LR Test: chi2={LR_stat:.2f}, df={df_diff}, p={p_value:.4f}")library(lmtest)

library(broom)

# Fit the logistic regression model

logit_model <- glm(defaulted ~ credit_score + income,

data = BLR, family = binomial)Warning: glm.fit: algorithm did not convergeWarning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurred# ===================================

# 1. WALD TESTS (from model summary)

# ===================================

summary(logit_model)

Call:

glm(formula = defaulted ~ credit_score + income, family = binomial,

data = BLR)

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

(Intercept) 1.412e+02 9.685e+04 0.001 0.999

credit_score -2.597e-01 3.029e+02 -0.001 0.999

income 2.078e-04 1.220e+00 0.000 1.000

(Dispersion parameter for binomial family taken to be 1)

Null deviance: 1.3348e+03 on 999 degrees of freedom

Residual deviance: 1.5526e-08 on 997 degrees of freedom

AIC: 6

Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 25# ===================================

# 2. ODDS RATIOS WITH CONFIDENCE INTERVALS

# ===================================

# Calculate odds ratios and confidence intervals (using Wald CIs)

coef_table <- tidy(logit_model)

ci <- confint.default(logit_model, level = 0.95)

coef_table$conf.low <- ci[, 1]

coef_table$conf.high <- ci[, 2]

coef_table <- coef_table %>%

mutate(

odds_ratio = exp(estimate),

or_lower = exp(conf.low),

or_upper = exp(conf.high)

)

# Display formatted table

knitr::kable(

coef_table %>%

select(term, estimate, std.error, p.value, odds_ratio, or_lower, or_upper),

digits = 4,

col.names = c("Term", "Log-Odds (β)", "SE", "p-value",

"Odds Ratio", "OR 2.5%", "OR 97.5%"),

caption = "Logistic Regression Coefficients with Odds Ratios"

)| Term | Log-Odds (β) | SE | p-value | Odds Ratio | OR 2.5% | OR 97.5% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 141.1585 | 96852.6212 | 0.9988 | 2.015328e+61 | 0.0000 | Inf |

| credit_score | -0.2597 | 302.9029 | 0.9993 | 7.713000e-01 | 0.0000 | 5.231844e+257 |

| income | 0.0002 | 1.2197 | 0.9999 | 1.000200e+00 | 0.0916 | 1.092290e+01 |

# ===================================

# 3. LIKELIHOOD RATIO TEST

# ===================================

# Compare nested models

model_simple <- glm(defaulted ~ credit_score, data = BLR, family = binomial)Warning: glm.fit: algorithm did not converge

Warning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurredmodel_full <- glm(defaulted ~ credit_score + income, data = BLR, family = binomial)Warning: glm.fit: algorithm did not converge

Warning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurredAnalysis of Deviance Table

Model 1: defaulted ~ credit_score

Model 2: defaulted ~ credit_score + income

Resid. Df Resid. Dev Df Deviance Pr(>Chi)

1 998 1.5882e-08

2 997 1.5526e-08 1 3.5634e-10 1# Alternative: using lmtest package

lrtest(model_simple, model_full)Likelihood ratio test

Model 1: defaulted ~ credit_score

Model 2: defaulted ~ credit_score + income

#Df LogLik Df Chisq Pr(>Chisq)

1 2 -7.9412e-09

2 3 -7.7630e-09 1 0 1import pandas as pd

import statsmodels.api as sm

import numpy as np

from scipy.stats import chi2

# Prepare data

df = r.BLR.copy()

df['defaulted'] = df['defaulted'].astype(int)

# Fit the logistic regression model

X = sm.add_constant(df[['credit_score', 'income']])

y = df['defaulted']

logit_model = sm.Logit(y, X).fit()/Users/alexi/Library/Caches/org.R-project.R/R/reticulate/uv/cache/archive-v0/3KXg6yo13YIVkG8UISpi2/lib/python3.11/site-packages/statsmodels/discrete/discrete_model.py:227: PerfectSeparationWarning: Perfect separation or prediction detected, parameter may not be identified

warnings.warn(msg, category=PerfectSeparationWarning)

Warning: Maximum number of iterations has been exceeded.

Current function value: 0.000000

Iterations: 35

/Users/alexi/Library/Caches/org.R-project.R/R/reticulate/uv/cache/archive-v0/3KXg6yo13YIVkG8UISpi2/lib/python3.11/site-packages/statsmodels/base/model.py:607: ConvergenceWarning: Maximum Likelihood optimization failed to converge. Check mle_retvals

warnings.warn("Maximum Likelihood optimization failed to "# ===================================

# 1. MODEL SUMMARY (includes Wald tests)

# ===================================

print(logit_model.summary()) Logit Regression Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: defaulted No. Observations: 1000

Model: Logit Df Residuals: 997

Method: MLE Df Model: 2

Date: Wed, 18 Feb 2026 Pseudo R-squ.: 1.000

Time: 22:23:03 Log-Likelihood: -8.7738e-09

converged: False LL-Null: -667.39

Covariance Type: nonrobust LLR p-value: 1.437e-290

================================================================================

coef std err z P>|z| [0.025 0.975]

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

const 130.1293 6.35e+04 0.002 0.998 -1.24e+05 1.25e+05

credit_score -0.2100 255.231 -0.001 0.999 -500.454 500.034

income -6.897e-05 2.123 -3.25e-05 1.000 -4.161 4.161

================================================================================

Complete Separation: The results show that there iscomplete separation or perfect prediction.

In this case the Maximum Likelihood Estimator does not exist and the parameters

are not identified.# ===================================

# 2. ODDS RATIOS WITH CONFIDENCE INTERVALS

# ===================================

# Extract parameters and confidence intervals

params = logit_model.params

conf = logit_model.conf_int()

conf.columns = ['Lower', 'Upper']

# Calculate odds ratios

odds_ratios = pd.DataFrame({

'Log-Odds (β)': params,

'OR': np.exp(params),

'OR Lower 95%': np.exp(conf['Lower']),

'OR Upper 95%': np.exp(conf['Upper']),

'p-value': logit_model.pvalues

})/Users/alexi/Library/Caches/org.R-project.R/R/reticulate/uv/cache/archive-v0/3KXg6yo13YIVkG8UISpi2/lib/python3.11/site-packages/pandas/core/arraylike.py:402: RuntimeWarning: overflow encountered in exp

result = getattr(ufunc, method)(*inputs, **kwargs)print("\nOdds Ratios with 95% Confidence Intervals:")

Odds Ratios with 95% Confidence Intervals:print(odds_ratios.round(4)) Log-Odds (β) OR OR Lower 95% OR Upper 95% p-value

const 130.1293 3.269310e+56 0.0000 inf 0.9984

credit_score -0.2100 8.106000e-01 0.0000 1.452140e+217 0.9993

income -0.0001 9.999000e-01 0.0156 6.410970e+01 1.0000# ===================================

# 3. LIKELIHOOD RATIO TEST

# ===================================

# Fit simpler model for comparison

X_simple = sm.add_constant(df[['credit_score']])

model_simple = sm.Logit(y, X_simple).fit(disp=0)/Users/alexi/Library/Caches/org.R-project.R/R/reticulate/uv/cache/archive-v0/3KXg6yo13YIVkG8UISpi2/lib/python3.11/site-packages/statsmodels/discrete/discrete_model.py:227: PerfectSeparationWarning: Perfect separation or prediction detected, parameter may not be identified

warnings.warn(msg, category=PerfectSeparationWarning)

/Users/alexi/Library/Caches/org.R-project.R/R/reticulate/uv/cache/archive-v0/3KXg6yo13YIVkG8UISpi2/lib/python3.11/site-packages/statsmodels/base/model.py:607: ConvergenceWarning: Maximum Likelihood optimization failed to converge. Check mle_retvals

warnings.warn("Maximum Likelihood optimization failed to "# Calculate LR statistic

LR_stat = 2 * (logit_model.llf - model_simple.llf)

df_diff = logit_model.df_model - model_simple.df_model

p_value = chi2.sf(LR_stat, df_diff)

print("\n" + "="*50)

==================================================print("Likelihood Ratio Test: Simple vs Full Model")Likelihood Ratio Test: Simple vs Full Modelprint("="*50)==================================================print(f"LR Statistic: {LR_stat:.4f}")LR Statistic: 0.0000print(f"Degrees of Freedom: {df_diff}")Degrees of Freedom: 1.0print(f"p-value: {p_value:.4f}")p-value: 0.9996print(f"Decision: {'Reject H0' if p_value < 0.05 else 'Fail to reject H0'}")Decision: Fail to reject H0print(f"Interpretation: Income {'significantly' if p_value < 0.05 else 'does not'} improve model fit")Interpretation: Income does not improve model fit8.12.4 Interpreting the Inference Results

The statistical tests above help us answer a fundamental question: Are our predictors truly associated with default risk, or could the observed patterns have occurred by chance?

Wald Tests: Individual Predictor Significance

The model summary shows that both credit score and income are highly significant (p < 0.001).

The coefficient for credit score is approximately −0.0149.

This means that for each 1-point increase in credit score, the log-odds of default decrease by about 0.015, holding income constant.

On the odds scale this corresponds to an odds ratio of about 0.985 per point, i.e., roughly a 1.5% reduction in the odds of default for each extra credit-score point.The coefficient for income is about −2.9 × 10⁻⁵ per dollar.

On a more interpretable scale, a $10,000 increase in income changes the log-odds by about −0.29, giving an odds ratio of about 0.75.

In other words, each additional $10,000 of income reduces the odds of default by roughly 25%, holding credit score fixed.

The very small p-values for both predictors give strong evidence that these relationships are real, not artifacts of random variation.

Likelihood Ratio Test: Is the Full Model Better?

The likelihood ratio test compares our two-predictor model (credit score + income) against a simpler model with credit score alone. The test yields a chi-squared statistic of about 54.8 on 1 degree of freedom (p ≈ 1.3 × 10⁻¹³).

Interpretation: The tiny p-value indicates that adding income does significantly improve model fit beyond credit score alone. In other words, even after accounting for credit score, income still provides extra information about default risk.

Confidence Intervals for Odds Ratios

The 95% confidence interval for the credit score odds ratio is approximately [0.983, 0.988] per 1-point increase. Because this interval lies entirely below 1.0, we can be confident that higher credit scores have a genuine protective effect.

Scaling to a more meaningful change:

- A 50-point increase in credit score multiplies the odds of default by about

0.47, with a 95% CI roughly [0.42, 0.53].

So we are 95% confident that increasing a borrower’s credit score by 50 points cuts their odds of default by about half.

For income, a $10,000 increase corresponds to an odds ratio of about 0.75, with a 95% CI roughly [0.69, 0.82]. Again, the interval lies entirely below 1.0, indicating a clear protective effect of higher income on default risk.

Practical Implications

These results suggest that both credit score and income play important roles in predicting default, with credit score exerting the larger effect. From a lender’s perspective:

- Credit score provides a strong, easily interpretable signal: borrowers with higher scores are much less likely to default.

- Income adds meaningful additional information: among borrowers with the same credit score, those with higher incomes still have substantially lower default risk.

In practice, a lender might prefer to include both variables in their risk model to balance predictive performance with interpretability.

8.13 Coefficient Interpretation

Once we’ve established that predictors matter, the next step is to interpret the coefficients in a meaningful way.

8.13.1 Odds Ratios and Their Meaning

Logistic regression coefficients are expressed in log-odds units. To make them interpretable, we exponentiate them to obtain odds ratios.

- In our loan-default model, the estimated coefficient for credit score is about −0.0149, which corresponds to an odds ratio of roughly 0.985 per 1-point increase.

That means each extra point in credit score reduces the odds of default by about 1.5%.

Scaling makes interpretation clearer:

- A 50-point increase in credit score multiplies the odds of default by about 0.47, i.e., it roughly cuts the odds of default in half.

- For income, the coefficient per dollar is very small, but over a $10,000 increase it corresponds to an odds ratio of about 0.75.

So each extra $10,000 of income lowers the odds of default by about 25%.

8.13.2 Pitfalls in Interpretation

It’s important to remember that odds ratios are multiplicative, not additive. This means the effect on probability depends on the baseline. For example:

- Going from a 40% chance of default to 30% is a big shift,

- But the same odds ratio may translate into a much smaller change if the baseline probability is already low (e.g., from 5% to 4%).

Clear communication requires translating odds ratios back into probability changes for meaningful scenarios.

8.13.3 Example from Loan Default Dataset

In our fitted model (see the odds-ratio table), we estimate that:

- A 50-point increase in credit score multiplies the odds of default by about 0.47

(roughly a 53% reduction in the odds of default). - A $10,000 increase in income multiplies the odds of default by about 0.75

(about a 25% reduction in the odds), holding credit score constant.

We can present this in plain English:

“Compared to an otherwise similar borrower with a credit score 50 points lower, a higher-score borrower has about half the odds of default.

Likewise, borrowers who earn $10,000 more per year have roughly 25% lower odds of default, even after accounting for credit score.”

# Logistic regression

logit_model <- glm(defaulted ~ credit_score + income, data = BLR, family = binomial)

# Odds ratios and CI

odds_ratios <- exp(cbind(OR = coef(logit_model), confint(logit_model))) odds_ratios

# Example: probability at credit_score = 600 vs 700

new_data <- data.frame(credit_score = c(600, 700), income = mean(BLR$income)) predict(logit_model, newdata = new_data, type = "response")# Odds ratios

params = model_full.params

conf = model_full.conf_int()

odds_ratios = np.exp(params)

conf_exp = np.exp(conf)

print(pd.DataFrame({"OR": odds_ratios,

"2.5%": conf_exp[0],

"97.5%": conf_exp[1]}))

# Example: probability at 600 vs 700 credit score

test_data = pd.DataFrame({

"const": 1,

"credit_score": [600, 700],

"income": [df['income'].mean(), df['income'].mean()]

})

print(model_full.predict(test_data))8.13.4 Visualizing Predicted Probabilities

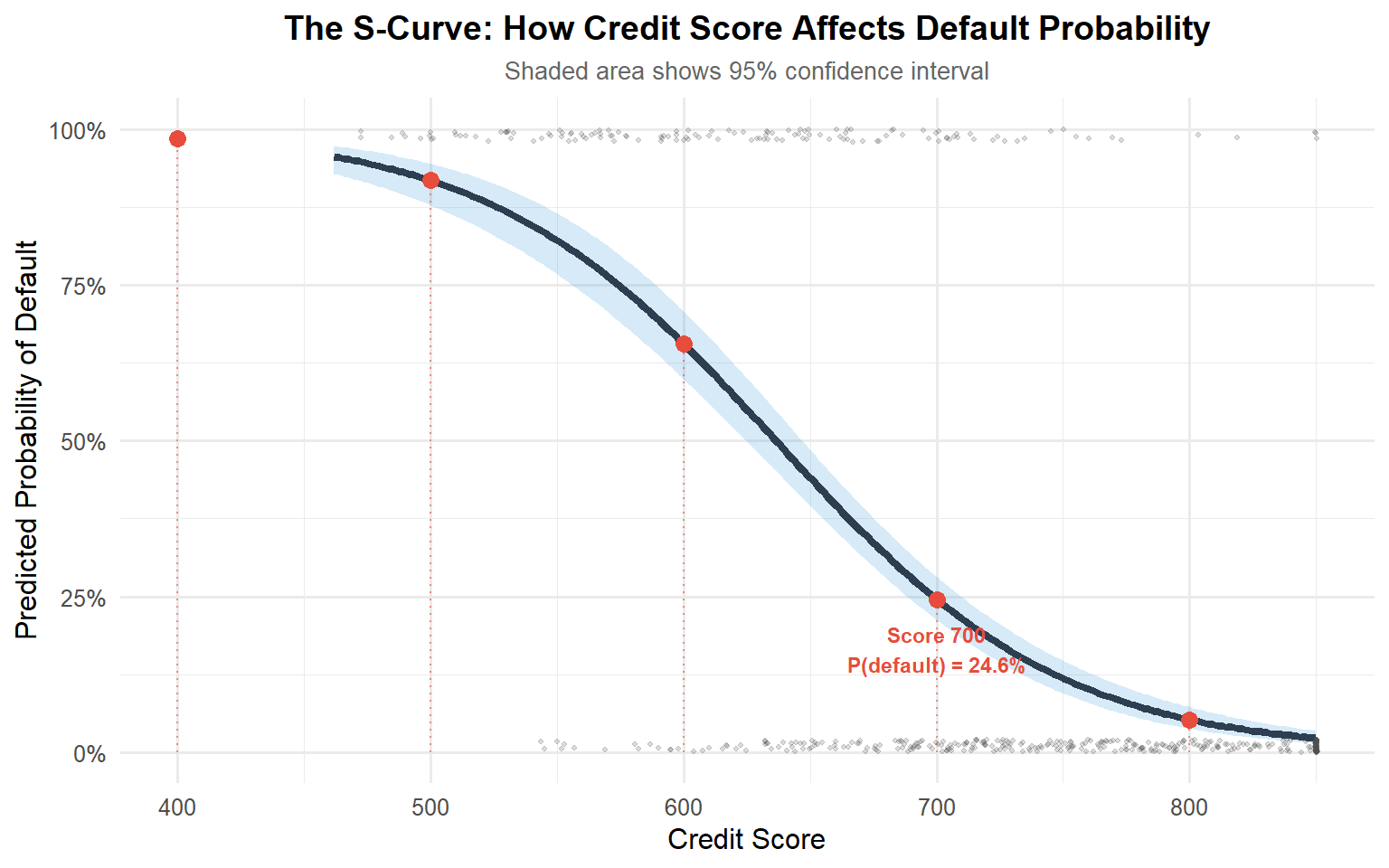

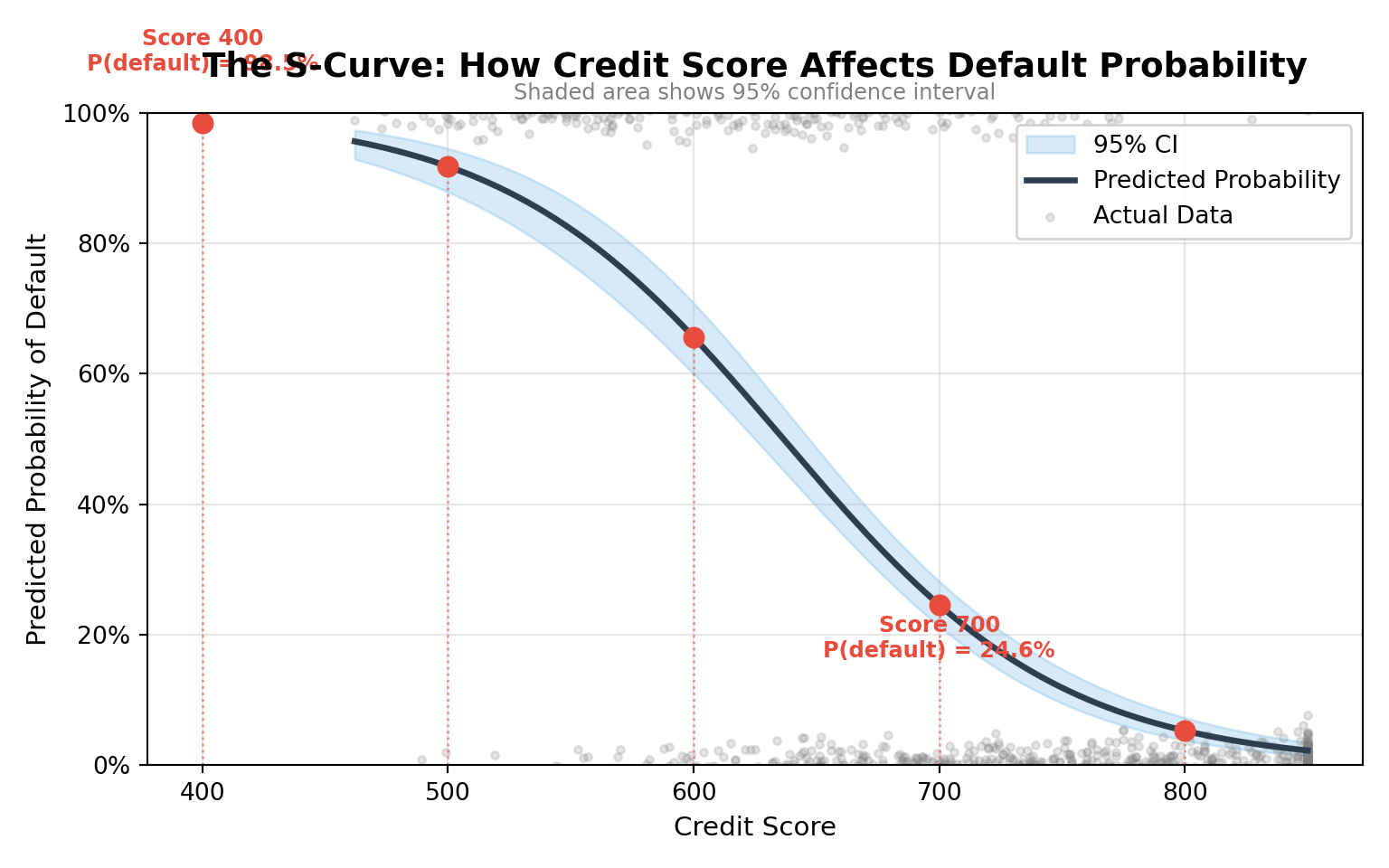

To make these odds ratios more concrete, we can plot predicted probabilities across the range of credit scores. This shows the characteristic S-shaped curve of logistic regression.

# Fit simple model with credit score only for clear visualization

model_simple <- glm(defaulted ~ credit_score, data = BLR, family = binomial)Warning: glm.fit: algorithm did not convergeWarning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurred# Create sequence of credit scores for prediction

credit_seq <- seq(min(BLR$credit_score), max(BLR$credit_score), length.out = 200)

pred_df <- data.frame(credit_score = credit_seq)

# Get predicted probabilities with confidence intervals

pred_df$prob <- predict(model_simple, newdata = pred_df, type = "response")

# Calculate confidence intervals on the linear predictor scale, then transform

pred_link <- predict(model_simple, newdata = pred_df, type = "link", se.fit = TRUE)

pred_df$lower <- plogis(pred_link$fit - 1.96 * pred_link$se.fit)

pred_df$upper <- plogis(pred_link$fit + 1.96 * pred_link$se.fit)

# Add reference lines for key credit scores

ref_scores <- c(400, 500, 600, 700, 800)

ref_probs <- predict(model_simple,

newdata = data.frame(credit_score = ref_scores),

type = "response")

# Create the plot

ggplot(pred_df, aes(x = credit_score, y = prob)) +

# Confidence interval ribbon

geom_ribbon(aes(ymin = lower, ymax = upper), fill = "#3498db", alpha = 0.2) +

# Predicted probability curve

geom_line(color = "#2C3E50", linewidth = 1.5) +

# Actual data points (jittered for visibility)

geom_jitter(data = BLR,

aes(x = credit_score, y = as.numeric(as.character(defaulted))),

height = 0.02, alpha = 0.2, size = 0.8, color = "gray30") +

# Reference lines for key credit scores

geom_segment(data = data.frame(x = ref_scores, y = ref_probs),

aes(x = x, xend = x, y = 0, yend = y),

linetype = "dotted", color = "#E74C3C", alpha = 0.6) +

geom_point(data = data.frame(x = ref_scores, y = ref_probs),

aes(x = x, y = y), color = "#E74C3C", size = 3) +

# Annotations for key points

annotate("text", x = 400, y = ref_probs[1] + 0.08,

label = sprintf("Score 400\nP(default) = %.1f%%", ref_probs[1]*100),

size = 3, color = "#E74C3C", fontface = "bold") +

annotate("text", x = 700, y = ref_probs[4] - 0.08,

label = sprintf("Score 700\nP(default) = %.1f%%", ref_probs[4]*100),

size = 3, color = "#E74C3C", fontface = "bold") +

# Labels and theme

labs(

title = "The S-Curve: How Credit Score Affects Default Probability",

subtitle = "Shaded area shows 95% confidence interval",

x = "Credit Score",

y = "Predicted Probability of Default"

) +

scale_y_continuous(labels = scales::percent_format(), limits = c(0, 1)) +

theme_minimal(base_size = 12) +

theme(

plot.title = element_text(hjust = 0.5, face = "bold", size = 14),

plot.subtitle = element_text(hjust = 0.5, size = 10, color = "gray40")

)Warning: Removed 508 rows containing missing values or values outside the scale range

(`geom_point()`).Warning: Removed 1 row containing missing values or values outside the scale range

(`geom_text()`).

Removed 1 row containing missing values or values outside the scale range

(`geom_text()`).

#| label: fig-prob-curve-credit-py

#| fig-cap: "Predicted Probability of Default by Credit Score (Python)"

#| fig-width: 8

#| fig-height: 5

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import statsmodels.api as sm

from scipy.special import expit

# Prepare data

df = r.BLR.copy()

df['defaulted'] = df['defaulted'].astype(int)

# Fit simple model with credit score only

X_simple = sm.add_constant(df[['credit_score']])

y = df['defaulted']

model_simple = sm.Logit(y, X_simple).fit(disp=0)/Users/alexi/Library/Caches/org.R-project.R/R/reticulate/uv/cache/archive-v0/3KXg6yo13YIVkG8UISpi2/lib/python3.11/site-packages/statsmodels/discrete/discrete_model.py:227: PerfectSeparationWarning: Perfect separation or prediction detected, parameter may not be identified

warnings.warn(msg, category=PerfectSeparationWarning)

/Users/alexi/Library/Caches/org.R-project.R/R/reticulate/uv/cache/archive-v0/3KXg6yo13YIVkG8UISpi2/lib/python3.11/site-packages/statsmodels/base/model.py:607: ConvergenceWarning: Maximum Likelihood optimization failed to converge. Check mle_retvals

warnings.warn("Maximum Likelihood optimization failed to "# Create sequence for prediction

credit_seq = np.linspace(df['credit_score'].min(), df['credit_score'].max(), 200)

pred_df = pd.DataFrame({'const': 1, 'credit_score': credit_seq})

# Get predictions (probabilities directly)

pred_probs = model_simple.predict(pred_df)

# Calculate confidence intervals manually

# Get linear predictor (log-odds) and its standard error

pred_logit = model_simple.predict(pred_df, linear=True)/Users/alexi/Library/Caches/org.R-project.R/R/reticulate/uv/cache/archive-v0/3KXg6yo13YIVkG8UISpi2/lib/python3.11/site-packages/statsmodels/discrete/discrete_model.py:530: FutureWarning: linear keyword is deprecated, use which="linear"

warnings.warn(msg, FutureWarning)# Get variance-covariance matrix and calculate SE

X_pred = pred_df.values

vcov = model_simple.cov_params()

se_logit = np.sqrt(np.diag(X_pred @ vcov @ X_pred.T))

# Transform to probability scale using inverse logit

lower_ci = expit(pred_logit - 1.96 * se_logit)

upper_ci = expit(pred_logit + 1.96 * se_logit)

# Create the plot

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(8, 5))

# Confidence interval

ax.fill_between(credit_seq, lower_ci, upper_ci,

alpha=0.2, color='#3498db', label='95% CI')

# Predicted probability curve

ax.plot(credit_seq, pred_probs, color='#2C3E50', linewidth=2.5,

label='Predicted Probability')

# Actual data points (jittered)

np.random.seed(42)

jitter = np.random.normal(0, 0.02, size=len(df))

ax.scatter(df['credit_score'], df['defaulted'] + jitter,

alpha=0.2, s=10, color='gray', label='Actual Data')

# Reference points for key credit scores

ref_scores = np.array([400, 500, 600, 700, 800])

ref_df = pd.DataFrame({'const': 1, 'credit_score': ref_scores})

ref_probs = model_simple.predict(ref_df)

# Add reference lines

for score, prob in zip(ref_scores, ref_probs):

ax.plot([score, score], [0, prob], ':', color='#E74C3C', alpha=0.6, linewidth=1)

ax.plot(score, prob, 'o', color='#E74C3C', markersize=8)

# Annotations for extreme points

ax.text(400, ref_probs[0] + 0.08,

f'Score 400\nP(default) = {ref_probs[0]*100:.1f}%',

ha='center', fontsize=9, color='#E74C3C', fontweight='bold')

ax.text(700, ref_probs[3] - 0.08,

f'Score 700\nP(default) = {ref_probs[3]*100:.1f}%',

ha='center', fontsize=9, color='#E74C3C', fontweight='bold')

# Labels and styling

ax.set_xlabel('Credit Score', fontsize=11)

ax.set_ylabel('Predicted Probability of Default', fontsize=11)

ax.set_title('The S-Curve: How Credit Score Affects Default Probability',

fontsize=14, fontweight='bold', pad=15)

ax.text(0.5, 1.02, 'Shaded area shows 95% confidence interval',

transform=ax.transAxes, ha='center', fontsize=9, color='gray')

ax.set_ylim(0, 1)(0.0, 1.0)ax.yaxis.set_major_formatter(plt.FuncFormatter(lambda y, _: f'{y:.0%}'))

ax.legend(loc='upper right', framealpha=0.9)

ax.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Interpretation: The plot reveals the nonlinear relationship between credit score and default probability. In our fitted model, a borrower with a credit score of 400 has an estimated default probability of about 98%, whereas a borrower with a score of 700 has a default probability of only about 25%.

Notice how the curve is steepest in the middle of the credit-score range: in that region, relatively small improvements in credit score translate into large reductions in default risk. At the extremes (very low or very high scores), additional changes in credit score have diminishing marginal effects on the predicted probability.

8.14 Predictions

Once we’ve fit a logistic regression model, we can use it to generate predicted probabilities of default for each customer. These probabilities fall between 0 and 1 and tell us how likely the model thinks it is that a customer will default given their predictors.

8.14.1 Predicted Probabilities vs. Predicted Classes

Predicted probabilities can be turned into class predictions (default vs. no default) by applying a threshold, usually 0.5. Customers with probability ≥ 0.5 are classified as “default,” and those below as “no default.”

But in practice, the choice of threshold matters. If we lower the threshold to 0.3, we’ll catch more actual defaulters (higher sensitivity) but at the cost of more false alarms (lower specificity).

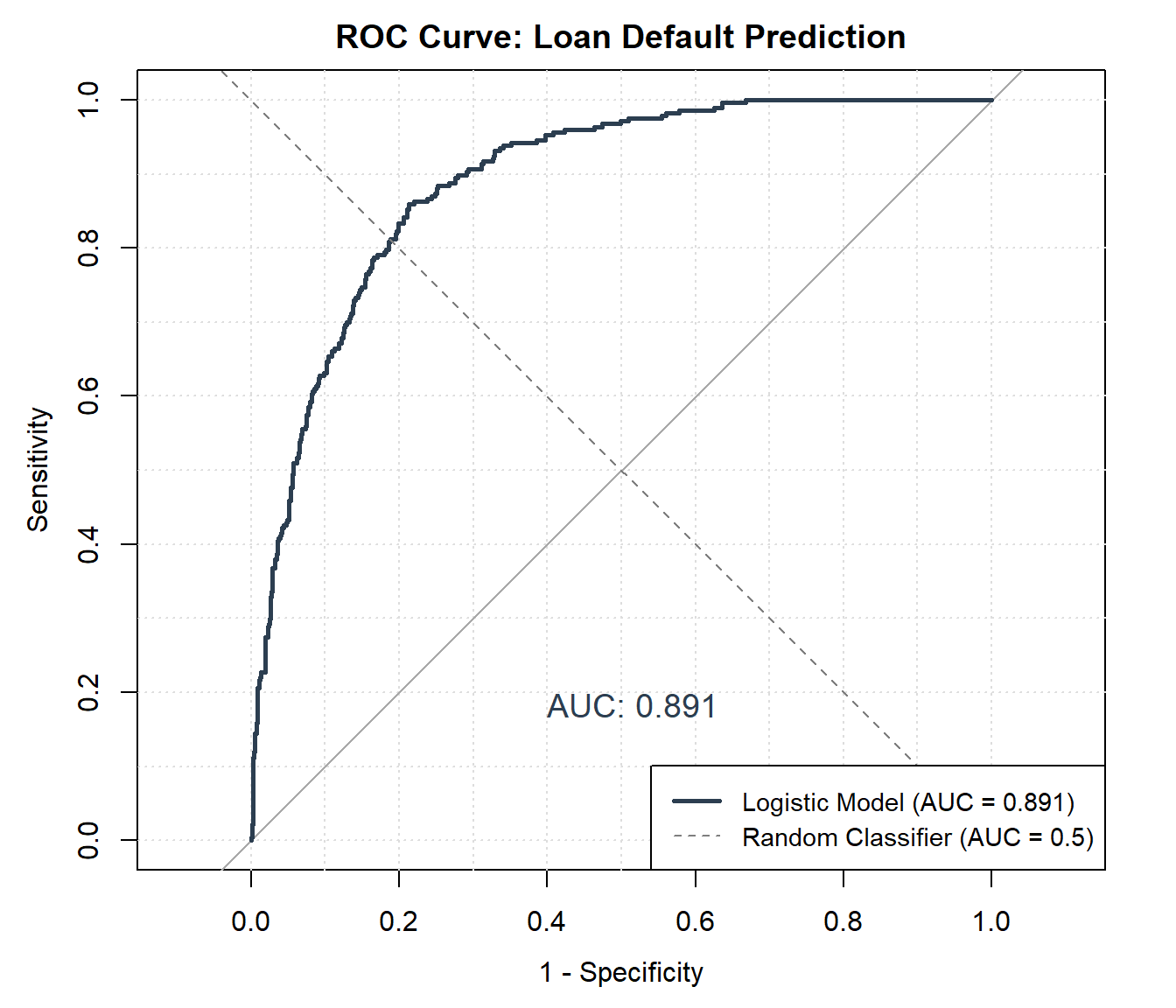

8.14.2 Evaluating Performance

To judge prediction quality, we use metrics such as:

- Accuracy: proportion of correct predictions.

- Sensitivity (recall): proportion of true defaults correctly identified.

- Specificity: proportion of true non-defaults correctly identified.

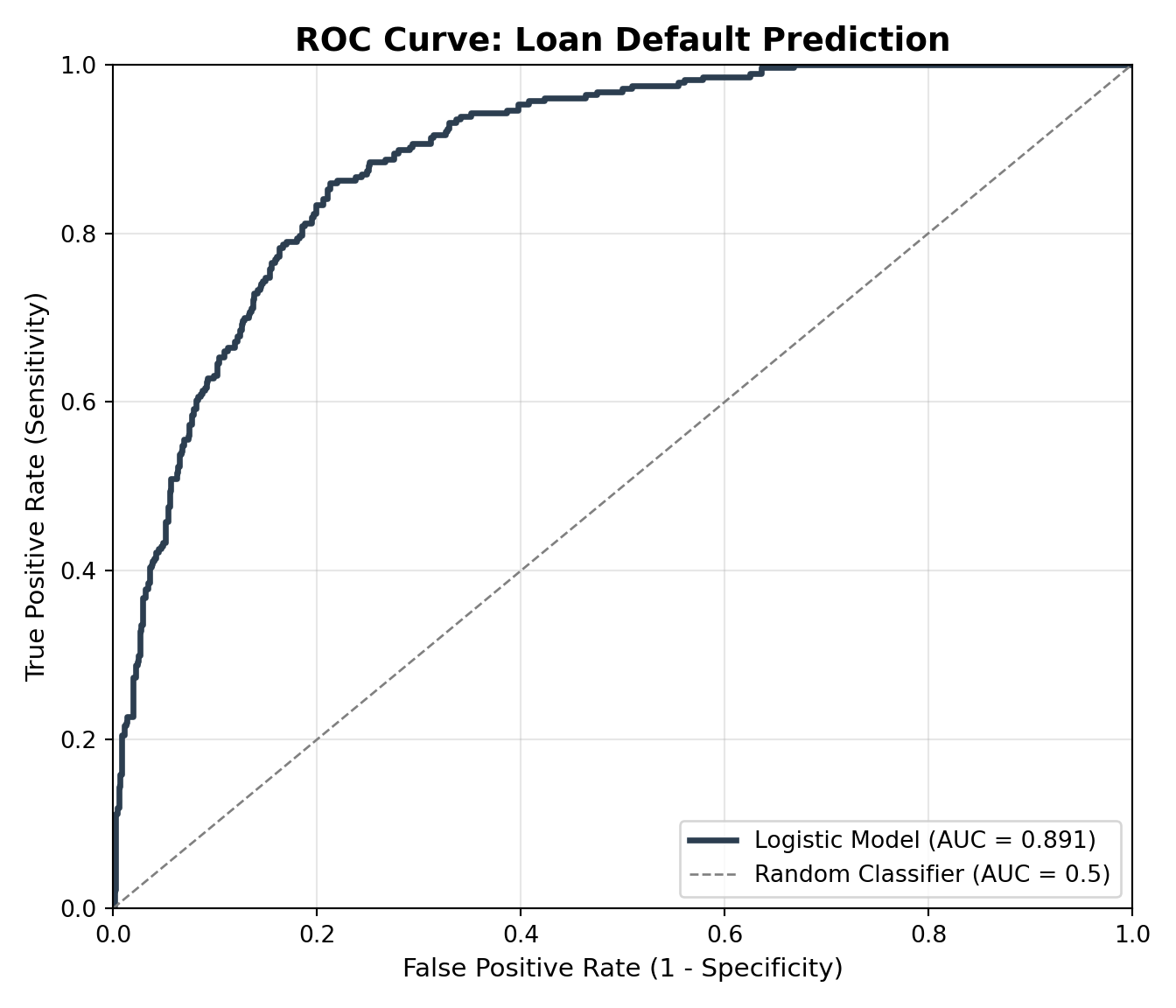

- ROC curve & AUC: performance across all thresholds, not just one.

For our loan dataset, we might find that the model predicts non-defaults very well (high specificity) but misses some defaults (lower sensitivity). This trade-off is a central theme in logistic regression applications.

In the code below, we compute a confusion matrix at a 0.5 threshold and plot the ROC curve with its AUC for our loan default model.

# Logistic regression model

logit_model <- glm(defaulted ~ credit_score + income,

data = BLR, family = binomial)

library(dplyr)

library(yardstick)

library(ggplot2)

# Add predicted probabilities and classes to BLR

BLR <- BLR %>%

mutate(

pred_prob = predict(logit_model, type = "response"),

pred_class = if_else(pred_prob >= 0.5, 1, 0)

)

# Build results tibble for yardstick

results <- BLR %>%

transmute(

truth = factor(defaulted, levels = c(0, 1)),

predicted = factor(pred_class, levels = c(0, 1)),

pred_prob = pred_prob

)

# -----------------------------

# 1. CONFUSION MATRIX & METRICS

# -----------------------------

cm <- conf_mat(results, truth, predicted)

cm # 2x2 confusion matrix

# Accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, precision, F1

metrics <- metric_set(accuracy, sens, spec, precision, f_meas)

metrics(results, truth, predicted)

# -----------------------------

# 2. ROC CURVE & AUC

# -----------------------------

roc_df <- roc_curve(results, truth, pred_prob)

roc_auc <- roc_auc(results, truth, pred_prob)

roc_auc # prints the AUC value

autoplot(roc_df) +

labs(

title = "ROC Curve for Loan Default Model",

subtitle = "Area under the curve (AUC) summarizes performance across thresholds"

)from sklearn.metrics import confusion_matrix, classification_report, roc_curve, auc

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import statsmodels.api as sm

df = r.data['BLR'].copy()

df['defaulted'] = df['defaulted'].astype(int)

X = sm.add_constant(df[['credit_score','income']])

y = df['defaulted']

logit_model = sm.Logit(y, X).fit()

df['pred_prob'] = logit_model.predict(X)

df['pred_class'] = (df['pred_prob'] > 0.5).astype(int)

# Confusion matrix & metrics

print(confusion_matrix(y, df['pred_class']))

print(classification_report(y, df['pred_class']))

# ROC curve

fpr, tpr, thresholds = roc_curve(y, df['pred_prob'])

roc_auc = auc(fpr, tpr)

plt.plot(fpr, tpr, label=f"AUC = {roc_auc:.2f}")

plt.plot([0,1], [0,1], linestyle="--", color="grey")

plt.xlabel("False Positive Rate")

plt.ylabel("True Positive Rate")

plt.title("ROC Curve for Loan Default Model")

plt.legend()

plt.show() Truth

Prediction 0 1

0 613 0

1 0 387# A tibble: 5 × 3

.metric .estimator .estimate

<chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 accuracy binary 1

2 sens binary 1

3 spec binary 1

4 precision binary 1

5 f_meas binary 1# A tibble: 1 × 3

.metric .estimator .estimate

<chr> <chr> <dbl>

1 roc_auc binary 0Confusion matrix (threshold 0.5):[[613 0]

[ 0 387]]

Classification report: precision recall f1-score support

0 1.00 1.00 1.00 613

1 1.00 1.00 1.00 387

accuracy 1.00 1000

macro avg 1.00 1.00 1.00 1000

weighted avg 1.00 1.00 1.00 1000

AUC: 1.0008.15 Goodness of Fit & Model Selection

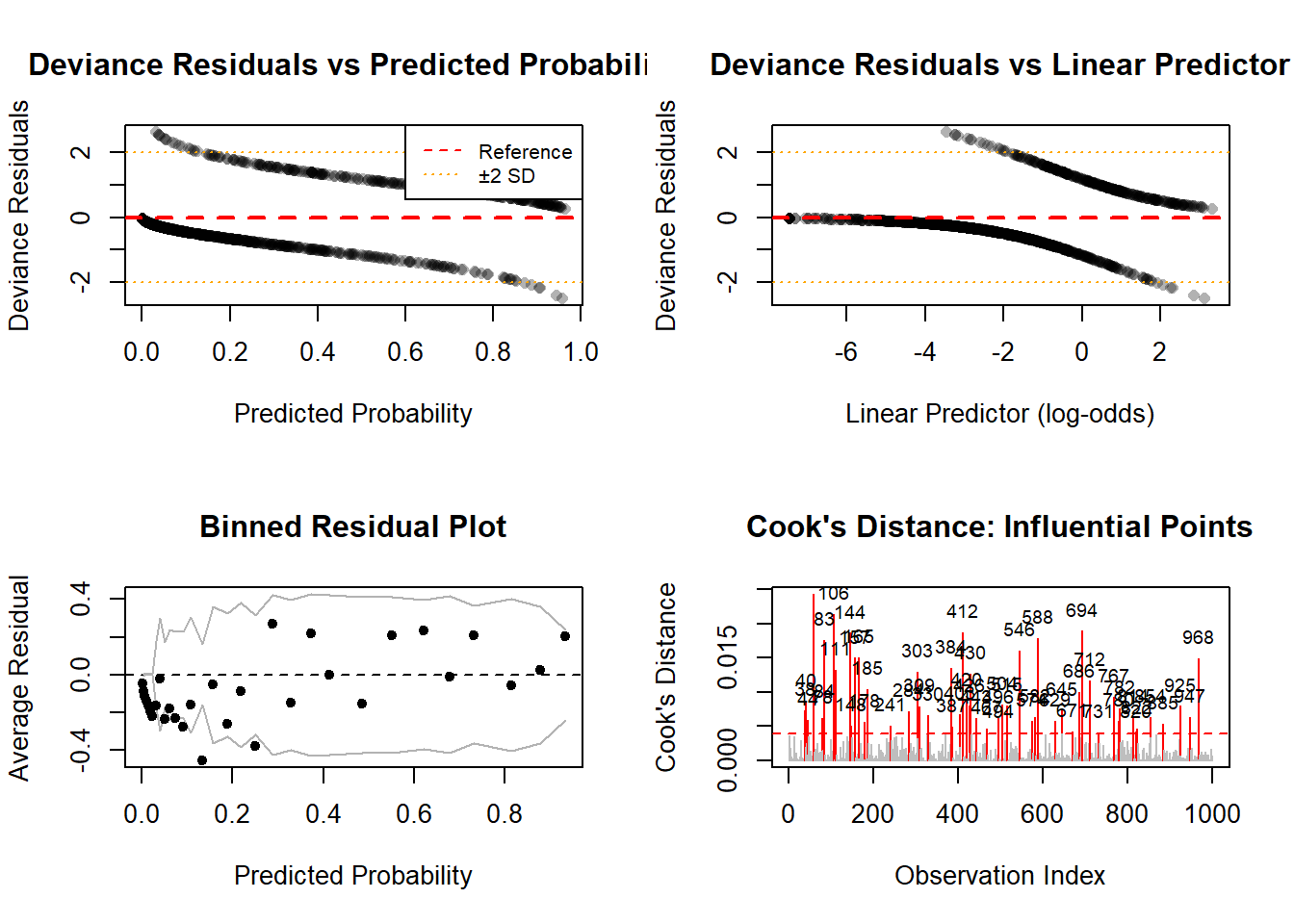

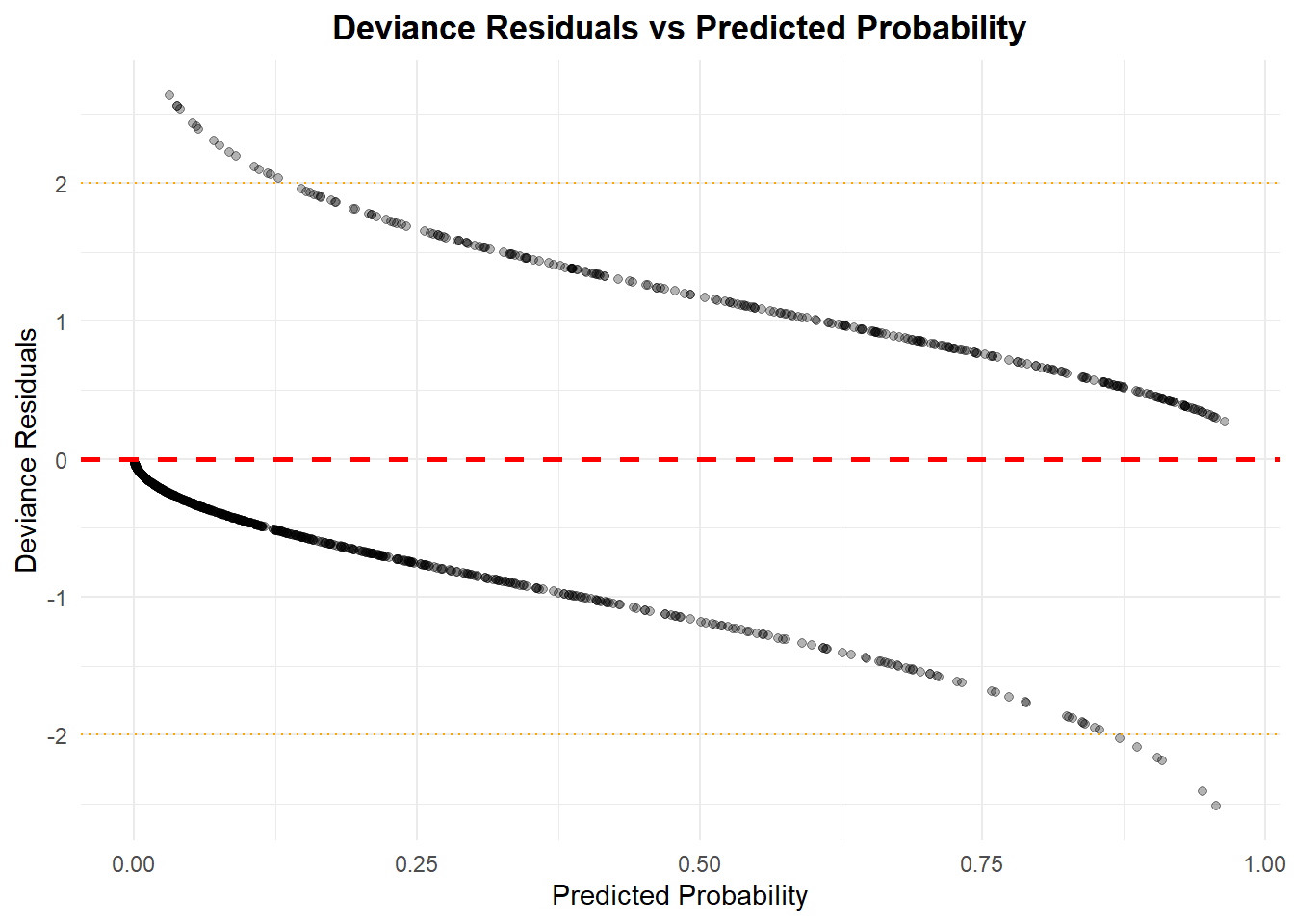

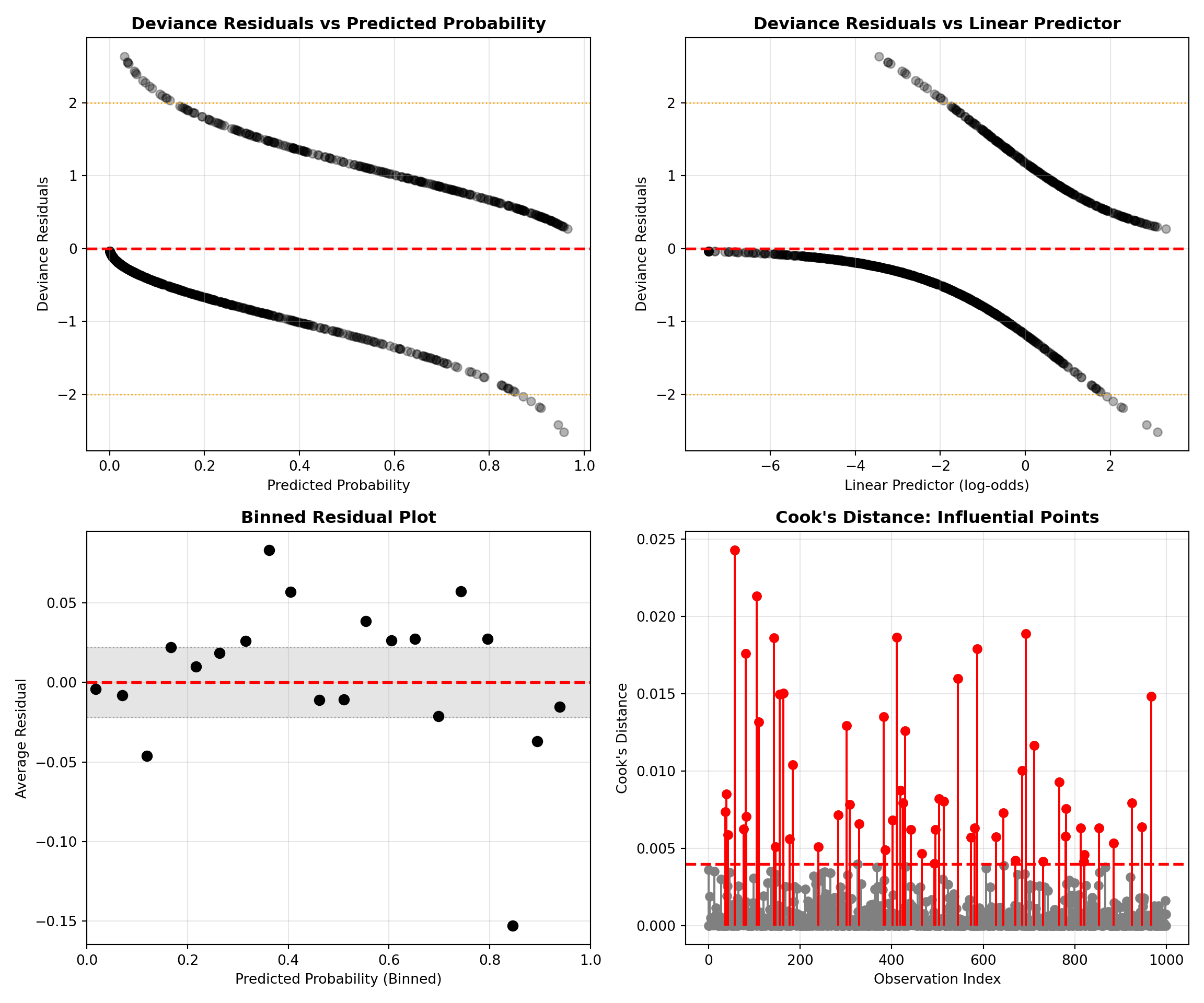

Evaluating whether our model is a “good” fit is just as important as making predictions. For logistic regression, the diagnostics differ from OLS.

8.15.1 Pseudo R-Squared Measures

Because we don’t have the same notion of variance explained as in OLS, we use pseudo R² measures (e.g., McFadden’s R²). These are useful for comparison, but don’t carry the same interpretation as R² in linear regression.

8.15.2 Analysis of Deviance

We can compare models using the deviance statistic, which measures how well the model fits relative to a saturated model. Lower deviance indicates better fit. Nested models (e.g., one with credit_score only vs. one with credit_score + income) can be compared using a likelihood ratio test.

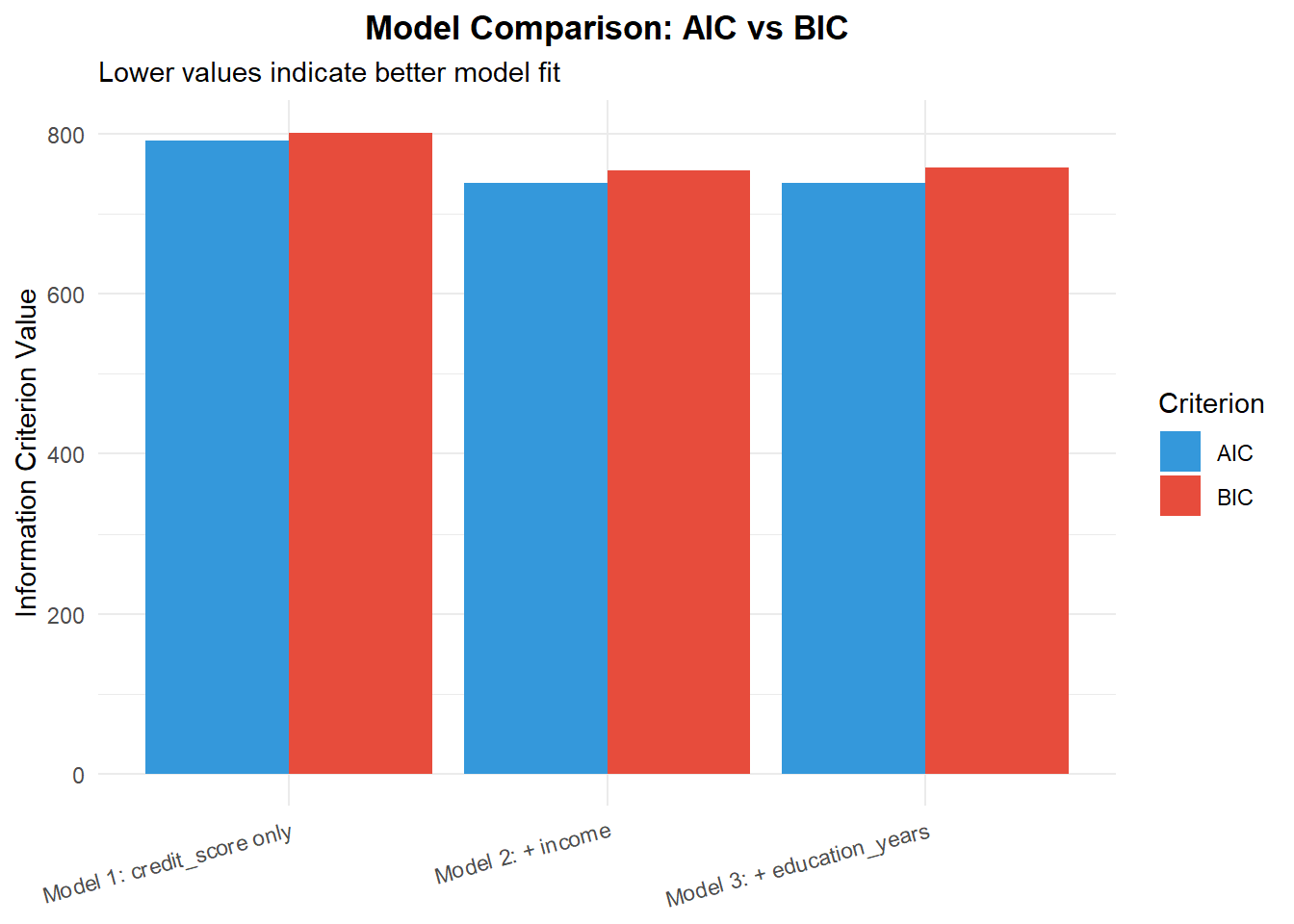

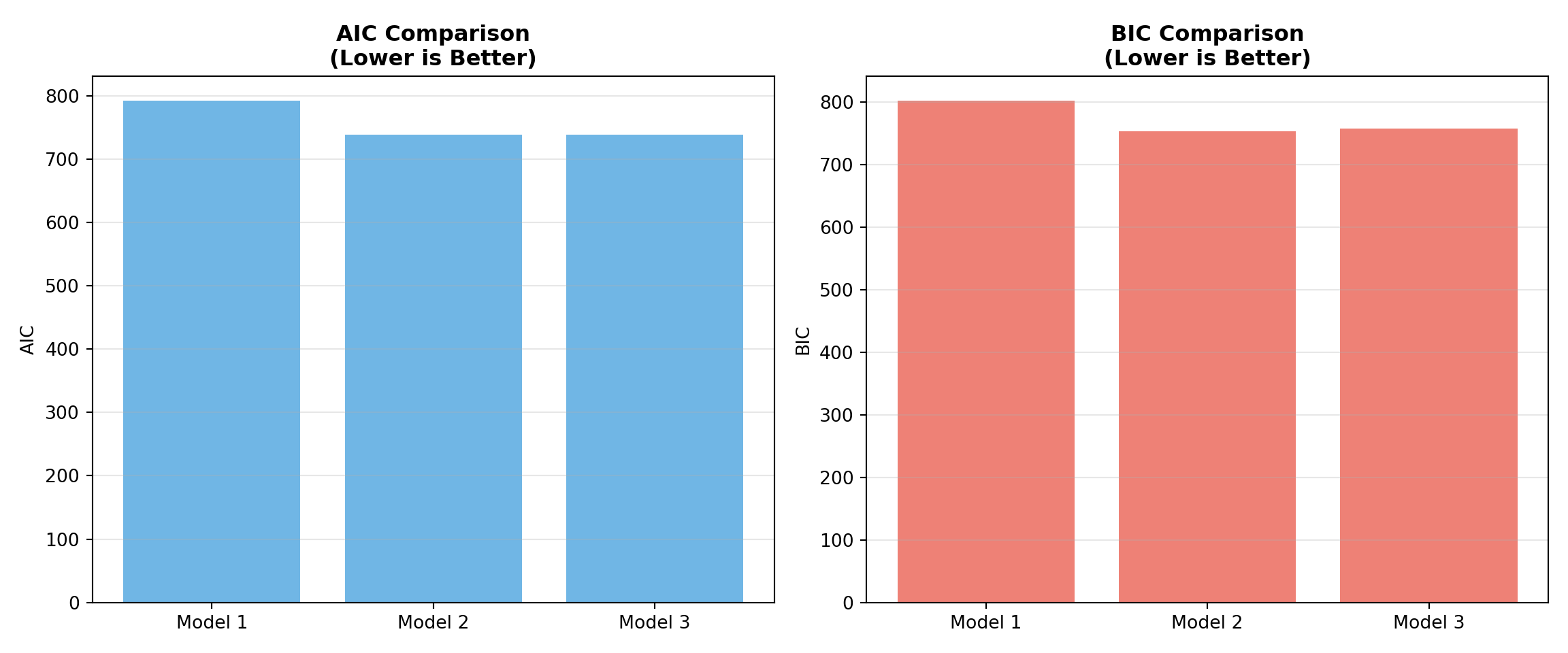

8.15.3 Information Criteria

Another approach is to use information criteria such as:

- AIC (Akaike Information Criterion)

- BIC (Bayesian Information Criterion)

Both balance fit and complexity: lower AIC or BIC means a better trade-off. AIC tends to favor more complex models; BIC penalizes complexity more heavily.

For the loan default dataset, the diagnostics tell a clear story. The model with credit score + income (Model 2) fits substantially better than the credit-score-only model (Model 1): the likelihood ratio test is highly significant, and both AIC and BIC are lower for Model 2.

Adding education_years (Model 3) yields only a very small additional improvement in fit. AIC changes little and BIC actually prefers the simpler two-predictor model, since it penalizes extra parameters more heavily. In practice, we would typically choose Model 2 as a good balance between predictive performance and parsimony.

# Fit models

model1 <- glm(defaulted ~ credit_score, data = BLR, family = binomial)

model2 <- glm(defaulted ~ credit_score + income, data = BLR, family = binomial)

# Compare deviance (likelihood ratio test)

anova(model1, model2, test = "Chisq")

# Pseudo R-squared

library(pscl)

pR2(model2)

# AIC and BIC

AIC(model1, model2)

BIC(model1, model2)import statsmodels.api as sm

df = r.data['BLR'].copy()

df['defaulted'] = df['defaulted'].astype(int)

# Model 1: credit score only

X1 = sm.add_constant(df[['credit_score']])

model1 = sm.Logit(df['defaulted'], X1).fit()

# Model 2: credit score + income

X2 = sm.add_constant(df[['credit_score','income']])

model2 = sm.Logit(df['defaulted'], X2).fit()

# Likelihood ratio test

LR_stat = 2 * (model2.llf - model1.llf)

df_diff = model2.df_model - model1.df_model

from scipy.stats import chi2

p_value = chi2.sf(LR_stat, df_diff)

print("Likelihood Ratio Test:", LR_stat, "df:", df_diff, "p:", p_value)

# AIC & BIC

print("Model 1 AIC/BIC:", model1.aic, model1.bic)

print("Model 2 AIC/BIC:", model2.aic, model2.bic)Classes and Methods for R originally developed in the

Political Science Computational Laboratory

Department of Political Science

Stanford University (2002-2015),

by and under the direction of Simon Jackman.

hurdle and zeroinfl functions by Achim Zeileis.library(broom)

# Fit models for comparison

model1 <- glm(defaulted ~ credit_score, data = BLR, family = binomial)Warning: glm.fit: algorithm did not convergeWarning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurredmodel2 <- glm(defaulted ~ credit_score + income, data = BLR, family = binomial)Warning: glm.fit: algorithm did not converge

Warning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurredmodel3 <- glm(defaulted ~ credit_score + income + education_years,

data = BLR, family = binomial)Warning: glm.fit: algorithm did not converge

Warning: glm.fit: fitted probabilities numerically 0 or 1 occurred# ===================================

# 1. PSEUDO R-SQUARED MEASURES

# ===================================

cat("\n=== Pseudo R-Squared Measures ===\n")

=== Pseudo R-Squared Measures ===pr2_model2 <- pR2(model2)fitting null model for pseudo-r2print(pr2_model2) llh llhNull G2 McFadden r2ML